|

A Department of Corrections official knew the extrajudicial practice was going on but little has been done to correct it.

The head of Louisiana’s prison system knew the state was keeping thousands of people behind bars long past their release date, according to a new court filing in a lawsuit by Rodney Grant, a man imprisoned 27 days past his court-ordered release date. In a May 23, 2019, deposition, James LeBlanc, secretary of the Department of Public Safety and Corrections (DOC), testified that he knew the extrajudicial practice was happening for at least seven years. LeBlanc supervised a 2012 internal study, which revealed that 2,252 people were held past their release dates each year at an average of 72 days of overdetention per person. The investigation also found that in January of that year, the DOC had a backlog of 1,446 people waiting for prison officials to compute their sentences. By the time their paperwork was processed, over 83 percent of people in the backlog had waited past their release dates. Louisiana, which was the nation’s incarceration capital until 2018, routinely keeps people behind bars for weeks, months, or sometimes years beyond their release dates. In February 2019 alone, the DOC imprisoned 231 people for an average of 44 days past their court-ordered release dates—or a total of more than 27 years in a single month. The DOC did not respond to a request for comment. “Our criminal justice system is based on the idea that if you are convicted, you do your time and then you are released,” William Most, who is representing Rodney Grant and whose eponymous law firm has helped numerous people who have remained imprisoned past their release dates, said in a press release. “In Louisiana, the state has completely failed to release people on time.” In 2012, DOC officials set a goal: reduce the number of people held past their release dates to 450 people per year at an average of 31 days per person. They didn’t succeed. According to a 2017 DOC internal investigation, an average of 200 people per month were still held an average of 49 days past their release dates. As of September 2018, the DOC acknowledged on its website that “it can take up to 12 weeks to calculate” a release date. It has since changed its wording to remove the estimate. Delays can be attributed in part to technology shortcomings. Local sheriffs and the state prison system do not have a shared computer system, which means prison officials must wait for the sheriff’s departments to submit physical paperwork regarding sentencing. In many parishes, this paperwork is driven from each parish to the DOC in Baton Rouge once a week. This means that a person sentenced after that particular day may have to wait another week in jail. That person may have to wait even longer for prison officials to calculate the amount of time served and the time remaining on their sentence, a process that can take over a week. Prison officials have rebuffed offers by other state actors to solve the delayed releases. Debbie Hudnall, the executive director of the Louisiana Clerks of Court Association, stated that she met with DOC officials numerous times and offered to begin emailing documents. But she testified to the state House of Representatives in December 2019 that officials told her that they “did not have the capability of receiving that.” Rodney Grant spent nearly one month behind bars beyond his court-ordered sentence. On June 27, 2016, Grant was arrested on a 15-year-old warrant for a burglary charge. Three days later, he pleaded guilty and the judge sentenced him to time served. He should have been released that same day. Instead, he was released 27 days later and only after his sentencing judge repeatedly contacted the DOC about his continued imprisonment. In 2017, Grant sued the DOC and LeBlanc, alleging that both violated his due process rights and committed false imprisonment by incarcerating him beyond his sentence. Grant is not the only one who spent additional time behind bars. Overdetention cost Ellis Ray Hicks months of his life. On Jan. 4, 2018, four days before his scheduled release date, Hicks learned that the date had changed—for the fourth time—to July. The computation officer had extended his release date again after Hicks had filed motions in court and Hicks’s family members had contacted him. Hicks’s extra prison time forced his aunt to postpone heart surgery until he was released and could care for her during recovery. It was not until Hicks contacted Most, the attorney, who in turn contacted the DOC, that Hicks was released on April 25, 2018. One week later, he took his aunt to the hospital for surgery, then nursed her through recovery. LeBlanc said in his May 2019 testimony that he wasn’t aware of any DOC employee being fired, demoted, or even reprimanded because of overdetention. Terry Lawson, the computation officer who extended Hicks’s release date, was not reprimanded, but Hicks is suing him, along with the DOC, for false imprisonment, negligence, and violation of his 14th and First Amendment rights. His suit is now in the U.S. Court for the Middle District of Louisiana. Hicks is not only seeking damages but also a permanent injunction that would require the DOC to end its practice of overdetention. “If Louisiana wants to give up its position as the highest-incarcerating state in the world, it should release the people who shouldn’t be in prison at all,” said David Lanser, an attorney who works with Most and is representing Hicks. Hicks agrees. He has been out of prison for nearly two years. “I suffered months of extra incarceration,” he told The Appeal. “It’s a large issue. It’s not just me—it’s a class of people. … I don’t want [DOC] to get away with it because they’ll just continue that activity.”

0 Comments

Marvin Zindler was a Houston news broadcaster in the 1980s and ’90s who viewers loved to hate, or maybe more accurately, “hated to love.”

He was a consumer champion of Houston’s poor. He was famous for concluding his commentary with a grating, ear-splitting moniker: “It’s hell to be poor!” (You can find him on YouTube videos.) Back then, my young Baptist self was affronted with his on-air “profanity,” but I’ve come to learn that the poor of this nation live an existence too profane to express in words. This is especially true when the poor run afoul of the criminal justice system. For instance, years ago I was a chaplain on the pediatric ward where a patient’s mother asked me if I could drive her to a vehicle impound yard. She was in school, working and had two kids. She let her boyfriend drive her car to the hospital without a license, so police impounded the car. Her impound fees were $300 a day. Bad to worse, it was closing time on Friday. The couple lost their car because it wasn’t worth the cost of removing it from the impound. Impound can be a license to steal from the poor. In fact, according to a Sacramento Bee story in 2014, that’s literally what police did in King City, Calif., when they “... impounded cars of migrant workers in a kickback scheme to sell the cars.” The incident helped me see how easily problems snowball for the poor. Imagine if you were a single working mom, or a minimum-wage worker or on disability, like my brother. You were arrested on a misdemeanor. You couldn’t afford bail, so you remained in jail. This meant you lost your job at the coffee shop and couldn’t make rent. Quickly, you were out on the street with no way to feed your young child. All before guilt was ascertained. When a poor person is arrested or becomes ill, their problems grow exponentially. Across the country, the death penalty is in steep decline. But in September, the state’s attorney general sought execution dates for nine men, and its Supreme Court set dates for two of them.

In April 1996, Tony Carruthers, charged with kidnapping and murder, stood in a Tennessee courtroom. Despite the severity of the case against him—he was charged with three counts of first-degree murder and faced the death penalty—he did not have an attorney by his side. Carruthers represented himself. Two years earlier, Carruthers and James Montgomery were arrested in Memphis, accused of killing Marcellos Anderson, his mother Delois, and Anderson’s friend Frederick Tucker. The three disappeared on the night of Feb. 24, 1994, and their bodies were found seven days later, buried beneath a casket in a local cemetery. By the time his trial began in 1996, Carruthers had gone through six attorneys. He asked to have another attorney appointed to him, but the judge refused. He was convinced that Carruthers was trying to delay his trial and forced him to proceed pro se, or arguing on his own behalf. Carruthers’s self-representation in a triple murder case was made all the more perilous by the fact that the state’s case against him relied heavily on the grand jury testimony from a career informant, Alfredo Shaw. The Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University’s law school issued a report finding that over 45 percent of all wrongful convictions in death penalty cases stem from lying by criminal informants, making “snitching the leading cause of wrongful convictions in U.S. capital cases.” Shaw’s story was deeply flawed; he said Carruthers confessed to him in a jail law library but later admitted he had not seen Carruthers since 1988. In a statement to local media before the trial, Shaw recanted his story. Prosecutors branded Shaw a liar and decided not to use him as a trial witness. But serving as his own attorney, Carruthers went forward with Shaw as a witness and, in a bumbling cross examination, mistakenly led Shaw to repeat his previously recanted testimony implicating him in the murders. On April 26, 1996, Carruthers was convicted and sentenced to death even though there was no forensic evidence linking him to the triple homicide. “The end of Mr. Carruthers pro se cross-exam of Alfredo Shaw is one of the most singularly inept, ineffective and disastrous cross-examinations, possible, one that seemed designed to secure not only a guilty verdict, but a death sentence,” Carruthers’s attorneys wrote in a post-conviction filing. Carruthers’s act of representing himself was so damaging that it eventually led to his co-defendant James Montgomery’s release. An appeals court granted him a new trial due to the prejudicial impact of being tried alongside a pro se defendant. In 2000, Montgomery agreed to a guilty plea to lesser charges of second-degree murder and was released in 2015. Nearly 24 years after the two were convicted, Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery requested that the state Supreme Court set execution dates for nine men, including Carruthers. In a Dec. 30 filing in opposition to the state’s motion to set an execution date for Carruthers, his attorneys with the Federal Public Defender for the Middle District of Tennessee wrote that by representing himself in court, he “did more to get himself convicted and sentenced to death than did the prosecution.” They also argued that Carruthers was incompetent to stand trial because he is seriously mentally ill “and that the manifestations of this serious mental illness include paranoid delusions, distorted thought processes, conspiratorial misapprehension of fact, a gross inability to make prudent decisions, and a complete inability to rationally perceive or understand the world around him. He also has significant brain damage which exacerbates the debilitating effects of his serious mental illness.” Carruthers’s case would be historic: If executed, he would be the first person in nearly a century to be put to death after being forced to represent himself at trial. Slatery’s request for a slew of executions in 2020 is so unusual because use of the death penalty is at near record lows. Death sentences declined from 298 in 1975 to 34 in 2019. Last year, 22 prisoners were executed nationwide, making it the second least active year for American death chambers since 1991. It was the fifth year in a row in which fewer than 30 prisoners were executed. For nearly a decade, Tennessee was part of this trend. The state didn’t execute a single prisoner from 2010 through 2017, although it did try. The state set execution dates for 10 men in 2014, scheduling regular executions between April 2014 and November 2015. All were called off because of legal challenges over the state’s execution methods. In early 2018, however, the death penalty returned to Tennessee. The state adopted a new lethal injection protocol, a three-drug cocktail that starts with the sedative midazolam. The protocol became notorious after it was used in botched executions in other states, including the execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014. After the midazolam was administered, Lockett struggled for several minutes, saying “something is wrong” and “this shit is fucking with my mind.” A nurse then closed blinds to observers and, according to The Intercept, “the blanket was lifted to reveal that the drugs were seeping into the tissue of his inner thigh instead of his veins, causing his skin to swell.” Officials called the governor’s office and then halted the proceedings—but by then Lockett was dead. Tennessee’s new protocol came with warnings from the state’s own consultants that midazolam might not be sufficient to prevent a person from feeling the effects of the next two drugs, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride. The new protocol also prompted a legal challenge filed in February 2018 by 33 death row prisoners who argued that it would effectively torture them to death. That same month, Slatery asked the state Supreme Court to schedule executions for eight men and asked that all the dates be set before June 1 due to concerns about the acquisition of execution drugs. That request was denied, but the court did start scheduling men to die, albeit on a slightly slower timeline. Beginning with the execution of Billy Ray Irick on Aug. 9, 2018, Tennessee executed six men in less than 16 months, second only to Texas during that timeframe. Each of the men—Irick, Ed Zagorski, David Miller, Don Johnson, Stephen West, and Lee Hall—had a history of mental illness, childhood abuse, or both. West was being treated with powerful antipsychotic drugs up until his execution, and Hall was functionally blind. Another condemned man, Charles Wright, was spared only because he died of cancer months before his execution date. The next man scheduled to die in Tennessee is Nick Sutton, who is set to be executed in the electric chair on Thursday. In 1985, Sutton was sentenced to death for fatally stabbing a fellow prisoner. When the murder occurred, he was serving a life sentence for murdering his grandmother when he was 18 years old. In his request for clemency, submitted to Governor Bill Lee in mid-January, Sutton’s attorneys included affidavits from two former correction officers who describe incidents in which Sutton saved their lives. “I owe my life to Nick Sutton,” wrote former correction officer Tony Eden in one affidavit. Several members of his victims’ families support Sutton’s clemency effort, and Sutton’s case garnered the attention of legendary anti-death penalty activist Sister Helen Prejean who tweeted on Jan. 22 that “he has saved the lives of three different prison staff members. Nick Sutton should not be executed.” In a letter to the Tennessee governor accompanying the clemency request, Sutton’s attorney wrote that Sutton “has gone from a life-taker to a life-saver.” Tennessee’s execution spree comes as death chambers in formerly prolific death penalty states are dormant, with some even considering abolition. On Jan. 7, Louisiana marked a full decade without an execution. Oklahoma—which has carried out 112 executions since 1976, trailing only Virginia and Texas—has not executed anyone in five years. In mid-January, an Oklahoma state representative introduced House Bill 2876 which would abolish the death penalty. If the bill passes in the House it will join 21 other states that have abolished the death penalty. Although Tennessee is bucking the national trend regarding executions, the state’s prosecutors and juries have become reluctant to hand down death sentences. It has been more than 25 years since Tennessee juries sentenced more than 10 people to death. In the last five years, only one death sentence has been handed down. “Death sentences are a better indicator of public sentiment about the death penalty than executions are,” Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told The Appeal. “When you have a state in which there’s been one new death sentence in the last five years, that’s an indication that juries are not returning death sentences. That’s an indication that the death penalty is withering on the back end while political actors are involved on the other end in executions.” Perhaps the most critical actor behind the resurgence of Tennessee’s death penalty is Slatery, who was appointed attorney general in 2014 by the state Supreme Court after he served as former Governor Bill Haslam’s top legal adviser. Dunham called Slatery “an extremist among extremists,” and Slatery appeared intent on proving his pro-death penalty bona fides in 2019. On Sept. 20, Slatery announced that his office would challenge an agreement proposed by Davidson County (Nashville) District Attorney Glenn Funk, in which death row prisoner Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman was re-sentenced to life because of prosecutorial misconduct during his 1987 trial. Attorneys for Abdur’Rahman alleged that John Zimmerman, then an assistant district attorney, excluded Black people from serving as jurors in Abdur’Rahman’s trial. In 2015, Zimmerman held a training in which he allegedly said that in a case with Latinx defendants, he “wanted an all African American jury, because ‘all Blacks hate Mexicans.’” When agreeing to the re-sentencing, Funk conceded that there was “overt racial bias” in Abdur’Rahman’s trial. Funk said, “The pursuit of justice is incompatible with deception. Prosecutors must never be dishonest to or mislead defense attorneys, courts or juries.” Nashville Criminal Court Judge Monte Watkins agreed and said the deal would “remedy a legal injustice.” The challenge to the re-sentencing was a remarkable step aimed at overturning an agreement between a prosecutor and a judge. Abdur’Rahman was scheduled to be executed on April 16, but last month the Tennessee Supreme Court granted him a stay while the legal fight over his case continues. Slatery challenged the deal with Abdur’Rahman on the same day that he asked the state Supreme Court to set execution dates for nine men, including Carruthers. In mid-January, the court set 2020 execution dates for two of the nine—Harold Nichols on June 4 and Oscar Smith on Aug. 4—and there most likely will be more coming soon. In October, Slatery spokesperson Samantha Fisher said the office held off on filing motions to schedule execution dates because of litigation over execution methods. With that legal challenge resolved, she said, Slatery decided to file the nine motions at once. Fisher also contends that the requests for execution dates are not a matter of Slatery’s discretion. “The attorney general, by rule of the Tennessee Supreme Court, is ordered to file a motion in the Tennessee Supreme Court notifying the court of the status of a defendant’s litigation once the three-tiered appeals process has been exhausted,” Fisher told The Appeal. In court filings at the end of last year, Kelley Henry, a supervising assistant federal public defender who represents seven of the nine prisoners for whom Slatery sought execution dates, argued that four of the men lack the capacity to rationally understand that they are going to be killed, or why. Carruthers is one of them. When a forensic psychiatrist attempted to assess Carruthers, he declined to see her “and demanded her insurance paperwork so that he can be paid $3.3 million for her malpractice in attempting to see him,” according to the Dec. 30 filing from his attorneys. His attorneys also wrote that another psychiatrist observed that Carruthers believed his attorneys were involved in a “vast conspiracy within the legal system involving homosexual themes” and that he demanded “millions of dollars which he persists in believing the government owes him.” Carruthers’s case is reflective of the systemic issues with the death penalty, including the pervasiveness of mental illness in the condemned and the cluster of outlier counties pursuing the punishment. His case was heard by a jury in Shelby County (Memphis), which accounts for nearly half of Tennessee’s death row despite being home to less than 14 percent of the state’s population. “Since 2001, only eight of Tennessee’s 95 counties have imposed sustained death sentences,” Carruthers’s attorneys wrote in their December filing. “And, of the nine trials resulting in a death sentence since 2010, five were from Shelby County.” “Each of these cases,” Henry told The Appeal, “is a window into the brokenness of the Tennessee death penalty.” Florida cannot bar people with felony convictions from voting if they can’t pay court-issued fines and fees, a federal appeals court ruled on Wednesday. A panel of judges with the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court’s injunction, finding that the 17 named plaintiffs cannot be barred from voting because of their inability to pay their court-issued fines and fees. The court found that such a requirement violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. “Because the legal financial obligation requirement punishes those who cannot pay more harshly than those who can—and does so by continuing to deny them access to the ballot box—Supreme Court precedent leads us to apply heightened scrutiny,” the court wrote in its opinion. In November 2018, nearly 65 percent of Florida voters approved Amendment 4, a constitutional amendment to restore voting rights to most Floridians with felony convictions who have completed their sentence. Previously, Florida had been one of just four states that permanently disenfranchised everyone with a felony conviction for life. After its passage, the definition of when an individual has completed all terms of their sentence became fiercely debated. Just a few months later, the GOP-controlled legislature passed and Governor Ron DeSantis signed into law Senate Bill 7066, legislation requiring the payment of court-issued fines and fees before people could have their voting rights restored. The bill allowed courts to convert fines and fees into community service hours, and some state attorneys considered making efforts to waive fines and fees en masse, but the process proved complicated and difficult, given the decentralized way that financial obligations are tracked in Florida. The new law left many potential voters confused as to whether they owed fines and fees, unsure how to determine what they owed, and concerned that they might be committing another felony by registering to vote. Wednesday’s opinion comes one day after Florida’s voter registration deadline for the state’s March 17 primary. Those who have not yet registered because they thought they were ineligible will not be permitted to participate in the upcoming primary. Although the opinion only directly applies to the 17 named plaintiffs, both the parties and the court used broader language, understanding that it could soon mean that anyone with a felony conviction who owes fines and fees and is unable to pay them will be permitted to vote anyway. The court left it to the state to find a “reasonable,” “good faith” way to define the term “genuine inability to pay.” Research has shown that the vast majority of court-issued fines and fees go unpaid. University of Florida Professor Daniel Smith, an expert called by plaintiffs in the federal court lawsuit, compiled data from a majority of Florida counties and wrote in an August 2019 report that over 80 percent of people with felony convictions who had completed their terms of incarceration, parole, and probation had outstanding financial obligations. Over 37 percent of those people owed at least $1,000. Voting advocates called the Florida law a poll tax—invoking the strategy used to keep African Americans from voting in the Jim Crow South—and immediately filed multiple lawsuits. Wednesday’s ruling is in response to one of those lawsuits, filed by 17 people with felony convictions who say they have various financial hardships and cannot afford to pay off their fines and fees. In its opinion, the court explained that the right to vote under Amendment 4 cannot be tied to ability to pay. “These plaintiffs are punished more harshly than those who committed precisely the same crime—by having their right to vote taken from them likely for their entire lives,” the opinion said. “And this punishment is linked not to their culpability, but rather to the exogenous fact of their wealth.” Julie Ebenstein, senior staff attorney with the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project who argued the case before the Eleventh Circuit, praised the ruling. “The court unanimously ruled that a person’s right to vote cannot be contingent upon their ability to pay,” she said in a statement. “This law is a modern-day poll tax. This ruling recognizes the gravity of elected officials trying to circumvent Amendment 4 to create roadblocks to voting based on wealth.” Helen Aguirre Ferré, DeSantis’ communications director, said on Twitter that the state plans to ask the Eleventh Circuit to reconsider the case en banc. The state could also appeal that ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. As a result, it remains to be seen what effect the ruling will have on the 2020 election.

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NEXSTAR) — Over the last ten years, Congress has tripled the Department of Veterans Affairs’ funding for suicide prevention efforts more than $200 million.

But one bill could put more of a focus on funding in local communities. “We have 17 American veterans a day who commit suicide. That is a national tragedy,” Virginia Sen. Mark Warner (D) said. Warner says more must be done to prevent veteran suicide. He’s introduced a bill to help combat this crisis. “It would put money into the community to make sure veterans know where to turn on suicide assistance and prevention groups,” Warner said. He says the “Improve Well-being for Veterans Act” would provide money for local and state level services through non-profit organizations. “Anything we can do to lower that number of suicides today is a step in the right direction,” Warner said. A 2019 study by the Department of Veterans Affairs says more than 6,000 veterans have died because of suicide since 2008. Since 2005, that rate has been increasing. “It takes people. It takes interaction. It takes engagement,” Veterans of Foreign Wars spokesperson Terrence Hayes said. Hayes believes national support helps, but it’s really a problem that will be solved at the community level. “Having those community members, those neighbors, all those people that they come in contact with to actually be a part of the solution, I think that’s a great start,” Hayes said. Warner says he worked closely with Arkansas Republican Sen. John Boozman on this piece of legislation, and is confident bill will pass. The National Veterans Legal Services Program said the Defense Department failed to make public the “vast majority” of decisions made by military review boards

Associated Press NORFOLK, Va. — A veterans group says the Pentagon has reneged on its agreement to reopen a vast records database that helps service members who are appealing a less-than-honorable discharge. The National Veterans Legal Services Program said Tuesday that the Defense Department failed to make public the “vast majority” of decisions made by military review boards. Those boards grant or deny a veteran’s request to upgrade a less-than-honorable discharge. Veterans’ lawyers study those decisions in hopes of building successful arguments for their clients. Attorneys for the military said in court documents that they failed to keep their agreement because the records contained personal information that still needed to be redacted. DECATUR — The bronze and granite sculpture in downtown's Water Street Plaza Park has an amazing story to tell.

It depicts African-American soldiers rising from the bondage of slavery, joining the Union army and taking part in several important Civil War battles. "From the Cottonfield to the Battlefield," Iking Campbell, 9, said Monday, reading the plaque on the side of the sculpture. "In honor of the thousands of African-American soldiers who fought in the Civil War in defense of equal rights for all." Unveiled in 2009 by its creator, Decatur native Preston Jackson, the sculpture served as the first stop of "The Iconic Black History Scavenger Hunt & Soul Food Celebration" on Monday. Jarmese Sherrod, the event's organizer, said she started the event as a way to celebrate Black History Month by teaching area youth about the contributions of key figures in African-American history. Kids and volunteers pushed on despite gloomy weather conditions, many wearing ponchos donated by Boys & Girls Club of Decatur. Sherrod created the event through S.I.M.P., Inc., a company she established in 2002 that regularly hosts programs meant to inspire young students. Sherrod is also a Richland Community College professor. Around a dozen students, ranging from grades five to 12, were divided into teams and tasked with solving clues scattered around downtown Decatur. Each clue led to a local business and points were scored after teams uploaded a photo of the location through a smartphone app. Information detailing the life of Nancy Green, a former slave who later signed a lifetime contract to model the Aunt Jemima pancake mix in the 1890s, awaited the teams at Del's Popcorn Shop, for example. After the scavenger hunt, the group ate dinner at Jalyrih Grill, a local eatery at 820 N. Main St. that specializes in soul food. “It's a good time for us to learn about our culture and what happened back in the day," said Janese Sherrod, 16, who helped her mother, Jarmese, organize the scavenger hunt. The high school student was one of four leaders who helped guide teams of younger children around downtown. She also set up the smartphone app that kept score of each team since her mom is "not very good with technology." In addition to the history lesson, Jarmese Sherrod said the event also was intended to get the students better acquainted with downtown businesses. "There are so many great Decatur staples here in town, why not introduce them to some of those businesses early," Sherrod said. "They might be the next leaders that take over some of those businesses in the future." The federal government should maintain an asylum system that provides those fleeing persecution or torture with access to counsel, due process and full and fair adjudication rights that are consistent with U.S. and international law, according to a resolution the ABA House of Delegates passed overwhelmingly Monday at the midyear meeting in Austin, Texas.

Resolution 117, sponsored by the Commission on Immigration, also expresses the association’s opposition to recent government policies, including the Migrant Protection Protocols, or “Remain in Mexico” policy; metering, or refusing asylum-seekers entry due to limits on the number of individuals who can be processed; restrictions on asylum eligibility for individuals who did not apply for protection in transit countries; and the development of international agreements that allow the United States to transfer individuals to third countries without conducting asylum adjudications. Wendy Wayne, the chair of the Commission on Immigration and author of the report that accompanies the resolution, explained that it was drafted after she and other members of the commission spent a week volunteering with the ABA’s South Texas Pro Bono Asylum Representation Project in Harlingen, Texas. The program is more commonly known as ProBAR. “What we observed during this trip was a humanitarian crisis created by some of these policies and an immigration court system that does not uphold our values of justice or fairness,” she said. Wayne recalled that her group encountered nearly 2,500 people living on the street across the border in Matamoros, Mexico, with no running water and a total of five port-a-potties. The only food and shelter they received was from a group of teachers who walked over the international bridge every day with as much food and as many tents and yoga mats as they could carry. In addition to horrendous living conditions, she said the Migrant Protection Protocols makes it nearly impossible for asylum-seekers to access legal representation. Of the 50 cases Wayne and her group observed, only three of those seeking asylum had access to counsel. Wayne contended that the federal government’s recent immigration policies are even more troubling because they were imposed by unilateral executive action without input from Congress. The Commission on Immigration plans to coordinate with the ABA Governmental Affairs Office to make contacts in Congress, the Department of Homeland Security and Department of Justice aware of these recommendations and encourage changes in legislation and policies that uphold due process and fairness in the asylum system. WASHINGTON – Voting barriers for Native Americans have always existed, but polling cutbacks, discriminatory voter ID laws and lack of funding for elections are making things worse, advocates told a House panel Tuesday.

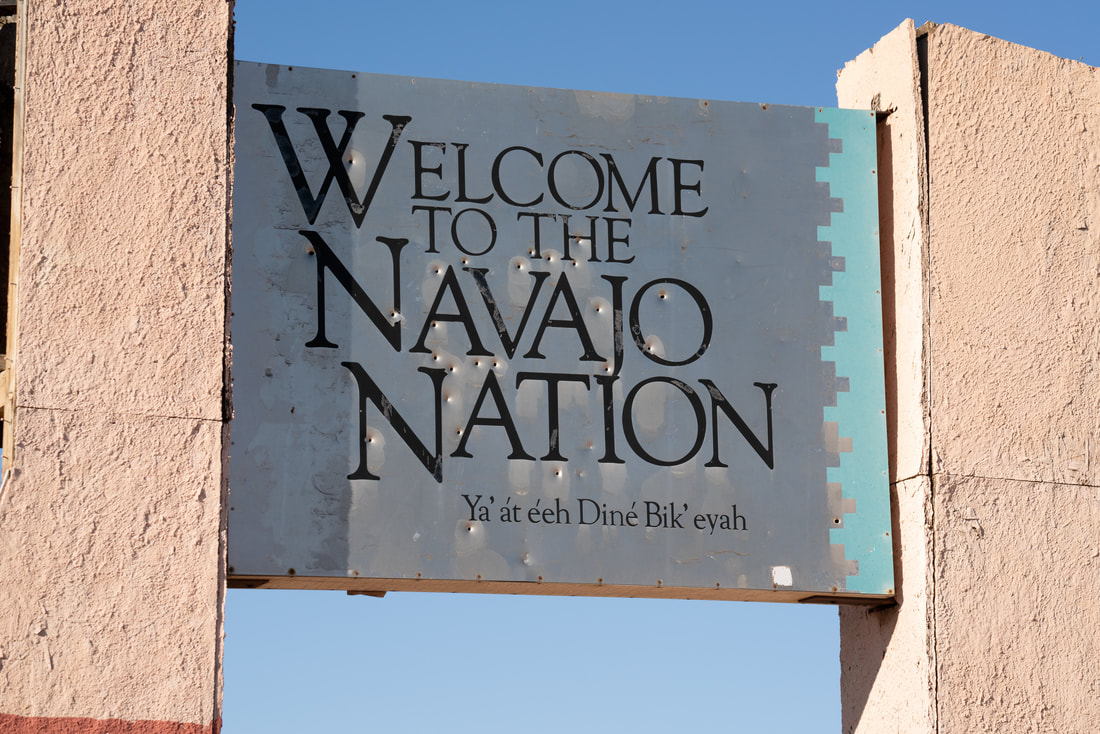

“What was old is new again,” said Rep. Marcia L. Fudge, D-Ohio, who chaired the hearing. “It is not only appropriate, but necessary, to hold a few hearings and make up for lost time.” The hearing came the same day a federal appeals court agreed to temporarily let Arizona restore its ban on “ballot-harvesting” – when one person collects another’s ballot – a tool that advocates said can increase voter turnout among groups like Native Americans. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Jan. 27 had overturned Arizona’s ban on ballot harvesting, one of two laws that it said reflected the state’s “long and unhappy history of official discrimination” in elections. But the appeals court Tuesday agreed to stay its ruling while Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich files an appeal with the Supreme Court. “Our job is to defend the law and we’re not going to let out-of-state special interests systematically dismantle our election integrity safeguards,” Brnovich said in a statement. The stay came down after the hearing by the House Administration Committee’s Subcommittee on Elections – but the topic of ballot harvesting was still a hot topic for witnesses. “We were encouraged by the 9th Circuit decision finding that the ballot harvesting ban was intentionally discriminatory,” said Jacqueline De León, a member of the Isleta Pueblo and a staff attorney with the Native American Rights Fund. “There is a lot of work still to be done in Arizona,” she said. Arizona is not alone. Indian Country voters face challenges to voting that include a lack of language assistance for Native speakers and difficulty complying with voter registration laws in areas where there may not be street addresses. “A majority of Navajo citizens residing on the reservation do not have traditional street addresses,” Navajo Nation Attorney General Doreen McPaul said in her testimony. She said that 70 of 110 Navajo Nation chapters do not have street names or numbered addresses, which accounts for at least 50,000 unmarked properties. McPaul said Arizona laws limiting ballot harvesting and rejecting ballots cast out of precinct had “significant hardship for Navajo voters.” She was challenged by Rep. Rodney Davis, R-Ill., who said ballot harvesting is “ripe for fraud.” But McPaul said it’s not uncommon on the reservation for people to have keys to other’s post office boxes and collect their mail. De León testified to other barriers to Native American voting that she and others identified through hearings in North Dakota, Oregon, California and Arizona. Those included geographical isolation, limited hours of government offices, technological barriers and homelessness. Tohono O’odham Chairman Ned Norris, on Capitol Hill for another hearing Tuesday, said people do not understand the sheer isolation of some tribal villages. “We think that if there was some level of understanding and an awareness, that we might be able to provide those polling places a little more accessible to the (Tohono O’odham) nation’s members, that could help address this issue,” Norris said. Problems are not limited to the reservation. Elvis A. Norquay, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, testified about being turned away from a North Carolina polling place in 2014 for not having an ID with an address. Norquay, a Marine Corps veteran who has been homeless, did not always have an address or the means to buy a new ID. “I was always happy to go vote,” he said, but “being turned away brought me down.” Fudge called Norquay’s story “striking,” and thanked the witnesses who showed up and “made clear the obstacles they face.” She said after the hearing that Congress needs to pass the Native American Voting Rights bill passed, which would “at least make a huge step toward making sure their right to vote is protected.” That bill aims to remove voting barriers for Native Americans by increasing voter registration sites, authorizing tribal ID cards for voting and providing resources. It has 94 co-sponsors, including all five Democrats from Arizona. “In an era of increasing voter suppression across this country, it’s more important than ever that we safeguard access to the ballot box,” said a statement from Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick, D-Tucson. Arizona State University law professor Patricia Ferguson-Bohnee echoed the need to protect voting rights among Native Americans, who may already feel disenfranchised. “You also have issues with people feeling like they’re not part of the Democratic process, so when you add barriers, it impacts their desire to vote and participate,” said Ferguson-Bohnee, director of the Indian Legal Clinic at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. "When you get disenfranchised and turned away, then you may not show up.” JACKSONVILLE, Fla. (CNN) — A 6-year-old special needs girl in Florida was involuntarily committed to a mental health facility because she was “out of control” at school, according to a Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office incident report.

Authorities were called to the Love Grove Elementary School last week after the girl was “destroying school property, attacking staff, out of control, and running out of school,” the report said. After a clinical social worker at the school told the responding officers that the girl was “a threat to herself and others,” she was taken to the River Point Behavioral Health for a 48-hour psychiatric evaluation under Florida’s Baker Act, the report states. The Baker Act allows mental health facilities to hold a person for up to 72 hours for evaluation. A law enforcement officer, a mental health professional or a Circuit Court judge may involuntarily commit an individual under the act if they are thought to be mentally ill, are refusing a voluntary examination and are thought to pose a threat to themselves or others. Between July 2017 and June 2018, there were 36,078 involuntary examinations initiated under the Baker Act for individuals under the age of 18 in Florida, according to a report from the state’s Department of Children and Families. An attorney for the girl’s mother, Reganel Reeves, said a school representative contacted the mother after the decision to admit the girl was made and she was on her way to the facility. Reeves said the girl is a special needs child who had “a temper tantrum at school.” She has been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, known as ADHD, a mood disorder and is being tested for autism, the attorney said. In a statement, Duval County Public Schools said the school staff followed the district’s procedure throughout the incident and then they notified the girl’s parent. The decision to admit the girl under the Baker Act was made by a licensed mental health care professional employed by Child Guidance, a private, non-profit community behavioral health care organization, the school district said. “When a student’s behavior presents a risk of self-harm or harm to others, the school district’s procedure is to call Child Guidance, our crisis response provider,” the school district said. ‘She’s been actually very pleasant,’ officer says Nadia’s mother, Martina Falk, still doesn’t know what exactly happened at the school but says her daughter should have never been taken to the mental health facility, her attorney said. The attorney said the girl is not able to “convey verbally what happened.” Her medicine had been changed recently, Reeves said, adding that might be a reason that she has been having a hard time. Her mother told the school about the medication change, but she says the school never mentioned any issues before the incident on February 4. Body camera video released by the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office shows the moment two officers exited the school with the girl, holding her hand and leading her to a police cruiser. When she asks if she’s going to jail, a female officer responds “no” and tells her not to throw any more chairs. Moments later, the female officer is heard saying, “She’s been actually very pleasant.” “I think it’s more of them not wanting to deal with it,” a male officer replied, according to the video. The school district said officers were not present during the “events” that led to the school to call Child Guidance nor when Child Guidance was intervening with the student. “It was the mental health counselor from Child Guidance, not the police officer or school personnel, who made the Baker Act decision,” the district said in a statement. “The student was calm when she left the school, but at that point, Child Guidance had already made the decision to Baker Act based on their intervention with the student.” Reeves said parents should have a chance to intervene before a mental health worker makes a decision because a phone call to the parent or guardian might help calm a child. The family wants an investigation into what happened, what actions were taken and who made the decision to send the girl to a mental health facility, Reeves said. “We want accountability,” the attorney said. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed