|

A pregnant woman living in a tent near the Kern River, a 66-year-old man suffering from asthma while living in a van, a middle-aged woman bedding down in a dark, cold abandoned industrial facility in east Bakersfield. They all have three things in common: They are homeless. They have medical needs. And each one was visited Thursday morning by a team of medical professionals practicing a type of guerrilla patient care known as "street medicine." "There is a recognition that our health care system as it is currently designed is not accessible to a lot of people. We need to re-imagine what that system should look like," said Corrine Feldman, a physician assistant, who with her husband, Brett Feldman, are veteran street medicine practitioners from the University of Southern California who were in Bakersfield on Thursday providing technical support to the primary team from Clinica Sierra Vista. Headed by Dr. Matthew Beare, the Clinica team met at 8:15 Thursday morning on Baker Street. By 8:45, they were walking into a hulking, abandoned corrugated metal structure in east Bakersfield — with Beare leading the way. The bearded doctor approached gently and with respect, identifying the team as medical practitioners. He knows unsheltered individuals may react with fear or panic to groups of outsiders entering a dark, abandoned industrial facility like this one. "This is a larger group than normal," he had cautioned the team earlier. "We need to be cognizant and not overwhelm the people there." As he walked toward a group of makeshift tents deep in the cavernous metal building, he called out to residents. "You guys need anything?" he asked. "We have dog food." Dog food is a way in. But so are first aid kits, hats, socks, feminine hygiene products. Corrine Feldman call the small gifts "tools of engagement." "They really are a link to creating a rapport," she said. Even something as simple as shoelaces can help create a bridge between the people who need medical care and the professionals who want to provide it. "Shoelaces not only lace up your shoes, they hold up pants, tents," Feldman said. "And pet food, it allows them to care for another living thing," she said. "That's really critical to feelings of self-worth." Especially when you're feeling worthless. But condoms are also handed out, as are clean syringes. If an IV drug user is going to use needles, he's much more likely to avoid contracting HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C if he sas access to "clean points." It's not an ideal arrangement, Beare acknowledged, but neither is living in a place with not even the most basic of creature comforts. The inside of the abandoned cotton gin looks post-Apocalyptic, the smell of soot and wood smoke from warming fires assault the senses. A gutted vehicle squats nearby. Trash. Shopping carts. Discarded building materials are everywhere. The rustling and cooing of pigeons can be heard high above in the rafters. There are three buildings, and as the team moves through them, each one cleaner than the first. Before the team departed, resident Victoria Rodriguez could be seen sitting on a portable folding stool as Medical student Justin Martin-Whitlock knelt on one knee and measured her blood pressure. Rodriguez was able to fill a prescription for meds thanks to the team's visits, which are weekly. Street Medicine is designed to deliver primary and urgent care to homeless people wherever they are. When the patients can't come to you, you go to them, Beare said, under bridges, along creeks and rivers, in shelters, soup kitchens, on skid row. All care, including medications, laboratory tests and diagnostic studies, are free. "I've volunteered two years with these guys," said Scott Dopp, who accompanied the team Thursday. "Three and a half years I was homeless. I learned a lot during that time, how to approach people, how to survive on the streets. "It's not easy to gain their trust," he said of the unsheltered, who are often victims of crimes, and even of well-meaning clean-up crews who will sometimes throw away the meager possessions of street people. "Dr. Beare, he's got a pretty good rapport with these folks," Dopp said. HOMELESS PETS ALSO HELPED Thursday's group was indeed larger that usual. It was joined by a veterinary team from the Street Dog Coalition, a nonprofit that provides free medical care and related services to pets of people experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness. Veterinarian Allyson Hannan and Vet Assistant Evelyn Flesner provided a vaccination and deworming to a puppy outside the industrial facility Thursday morning, they talked about how important it is to protect and honor the bond between all people and their animal families. The bond many unsheltered people have with their pets is strong, so strong that many will forego shelter for themselves if their pets are not allowed in. "This is our first time with this group," Flesner said of the street medicine team. "But we've done visits to other shelters." As the team moved from the industrial site to the Kern River floodplain near Oildale, it was not uncommon to see pets with many the unsheltered homeless. BOOTS ON THE GROUND When the team reached Riverview Park in south Oildale, they headed out on foot along trails that cut through riparian trees and underbrush near the river. Brett Feldman, the director of street medicine at USC, was there to observe and provide technical assistance. Feldman has practiced homeless medicine since 2007 and founded two street medicine programs in Allentown, Pa., as well as USC's street medicine program in Los Angeles. He is also the vice chair of the Street Medicine Institute, which facilitates and enhances the direct provision of health care to the unsheltered homeless where they live — in dozens of cities and countries all over the world. Feldman's job Thursday was to provide the sort of guidance and support to help Beare and others in developing their own street medicine programs. "The worst part of homelessness is not material want," Feldman said. "It's feeling unwashed, unwanted, uncared-for." One of the most common ways to help those who find themselves without a home, he said, is "harm reduction." Preventing hepatitis C, preventing infections, getting a homeless person in to see a dentist, and just showing you care are all forms of harm reduction. "Just being present is the biggest form of harm reduction," he said. Beare was present all morning. The doctor and his team must have walked two miles of trails, engaging everyone they saw. As case worker Maribel Bautista kept track of every medical contact, and helped set up appointments — and even transportation to clinics — Beare approached loners under bridges and couples in tents. Some of these temporary homes had an American flag flying proudly overhead, as if the residents wanted to say, "We're still Americans! Despite our circumstances, we're one of you." There was the couple with two dogs and a litter of eight young puppies. He was happy to take some dog food, condoms and hygiene kits, but he declined medical care — except for the puppies. Steven Schiavone, 59, said he chooses to live in the bush. He works two or three days a week and says he has as much money as he did when he was working for a corporate wage — because he doesn't have to pay rent or any number of other costs of living in a real house. But Schiavone had kind words for the street medicine team, and for Scott Di Stefano, who works with a group called Broken Chains, handing out an opioid inhibitor designed to save the life of someone in the thoes of an opioid overdose. "This is God's hands at work," Schiavone said of the work volunteers and medical professionals are doing. Beare and his team really got busy as they visited Church without Walls on Beardsley Avenue, where Ben Hanna is the pastor. Beare and his team assisted several at the church, patients with illnesses, possible infections, and one man who reported experiencing debilitating anxiety attacks. Watching Beare's approach, the way he forms relationships with patients who have nothing, and who may have little reason to trust a stranger, it soon becomes apparent why they do trust him. His empathy is close to the surface. His smile is like a father's or a big brother's. And his desire to help is draped across his shoulders like a stethoscope. But he knows the need is great and that one street medicine team may not be enough. "If others see the need and decide to join us in this effort," he said, "that would be the greatest reward." Steven Mayer can be reached at 661-395-7353. Follow him on Facebook and on Twitter: @semayerTBC.

1 Comment

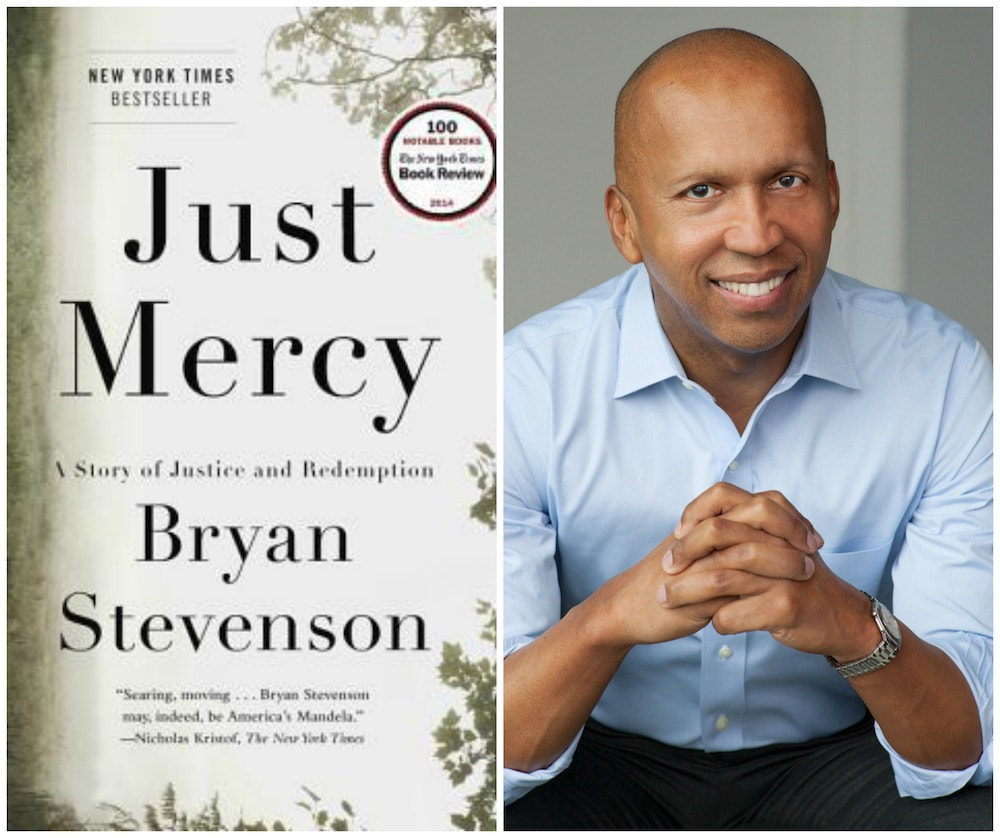

Few people are better qualified to weigh in on racial tensions and the criminal justice system in the United States than Bryan Stevenson. Mr. Stevenson, a Delaware native who founded and runs the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, is the subject of a recent film that highlights his efforts fighting for the disadvantaged, particularly death row inmates. The movie, “Just Mercy,” was released in December to positive reviews and big box office numbers. Starring Michael B. Jordan as Mr. Stevenson and also featuring Jamie Foxx and Brie Larson, the film is based on Mr. Stevenson’s memoir of the same name. A prominent lawyer and activist, Mr. Stevenson, 60, has spent decades fighting for greater equality in society, particularly a reformation of the criminal justice system he feels is vastly unfair to many, especially minorities and the poor. He has successfully argued cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and been involved in more than 135 reversals, relief or release from prison for death row inmates found to be wrongly convicted. ‘ORIGINAL SIN’ His life and work is in many ways is defined by America’s “original sin” of slavery and the racial animosity that exists today, more than 150 years after the nation abolished the practice. Raised in Milton, Mr. Stevenson had to deal with racism at an early age. “I started my education in a colored school in the 1960s. The effort at racial integration in schools like Milford was disrupted by fear and anger and it took lawyers and ‘rights’ to end the racial bigotry that defined education in our community,” he wrote in an email. “When I finished law school I wanted to use that same rule of law to protect people who are vulnerable, poor, incarcerated and condemned.” In a 2007 interview with New York University School of Law’s magazine, he recalled how regularly attending church as a child influenced his world view that people are more than their greatest sins, that they are, after all, human, with all the foibles that entails. That attitude of forgiveness continues to shape him today. After graduating from Cape Henlopen High School, Mr. Stevenson earned a degree from Eastern University and went to Harvard Law School. At the time, he said, he had never met a lawyer before. It was there he found his passion: fighting for those who could not fight for themselves. DEATH PENALTY Many see the death penalty as a way to protect against the worst of the worst, using it as a deterrent to crime and as punishment for some of society’s most dangerous offenders. But others view it differently. To Mr. Stevenson, capital punishment is disproportionately used against black and brown men, as well as individuals who lack the financial means to defend themselves. Compounding matters, he believes, is the fact far too many innocent people end up on death row. According to the Death Penalty Information Center, 167 inmates on death row have been exonerated and freed nationwide since 1973. That count does not include individuals who were executed and later found or believed to be innocent. While attending Harvard, he interned at the Southern Center for Human Rights, where he successfully argued for two inmates to have their death sentences replaced with prison time. In 1989, just a few years out of Harvard, he founded the Equal Justice Initiative. Today, the nonprofit employs nearly 40 people, according to its website, and has successfully argued before the nation’s top court that mandatory sentences of life without parole for individuals 16 and younger are unconstitutional. Mr. Stevenson found some notoriety and perhaps his greatest victory early in his career, when he led a crusade to free Walter McMillian, a black man sentenced to death in 1988 for killing a white woman two years earlier. The case had strong racial overtones: Not only did it take place in Alabama, one of the bastions of the Confederate “Lost Cause,” Mr. McMillian had been having an affair with a white woman. Because of the circumstances (including that Mr. McMillian had only a single prior misdemeanor on his record), Mr. Stevenson became very invested in the case. Despite finding evidence that had been withheld during the trial, he was unable to get the sentence overturned, prompting him to turn to an outside source: the media. After speaking with the lawyer, CBS’ “60 Minutes” aired a special on Mr. McMillian. He was freed a few years later. ‘JUST MERCY’ “Just Mercy” centers on the case, which Mr. Stevenson hopes can play at least some small part in changing public opinion. “It’s an enormous step forward to see the McMillian case as the subject of a major motion picture. Mostly because of the impact it can have in getting people to understand things about our system of justice,” he said. “If people saw what I see on a regular basis, they’d want the same things I want. They’d want people treated fairly, innocent people released, people in great need helped.” In 2018, he opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. In the decades since that ruling, he has continued to fight for criminal justice reform. Although the stigma is changing, he sees the attitude that drug addiction and mental health issues are criminal as backward, believing individuals need treatment and rehabilitation rather than punishment. “There is an epidemic of trauma and violence in some communities that requires an intervention that is informed by health perspectives which could not only lower the prison population but improve public safety,” he said. “We also need to recognize that a system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent is a system that needs to be reformed.” In 2016, Mr. Stevenson came to Delaware to argue for the abolition of the death penalty. Although lawmakers defeated a measure that would have repealed it, Delaware’s top court struck down the statute later that year, finding it to be unconstitutional. A bill to reinstate capital punishment is currently sitting in the legislature, although its path to passage is uncertain Delaware has taken several steps to make its criminal justice system less punitive in recent years, which gives hope to Mr. Stevenson the state can serve as a model for the country at large. RACISM To him, many of the nation’s issues can be traced back to racism, even if it is subconscious. “All over the nation there is a need for us to begin talking more honestly about our history of racial injustice in America. What we’ve done to Native people, black people and other groups that were disfavored is not something we should ignore if we want to become a healthy country,” he said. “I believe we need an era of truth and justice. We have to acknowledge the mistakes that have been made to have the awareness necessary to avoid problems in the future. Dr. King said that true peace is not the absence of violence but the presence of justice. “It takes courage but in Rwanda and Germany, something powerful has emerged from horrific violations of human rights. We should try to learn from that.” While some deny racism is a big problem in the country — a recent Gallup poll found 36 percent of respondents are somewhat or very satisfied with the state of race relations here — others can point to myriad ways it continues to impact Americans. That’s especially relevant for Mr. Stevenson and his life’s passion. Per the Death Penalty Information Center, since 1976, 21 executions have involved a white offender and black victim, compared to 294 with a white victim and black offender. The center also reports as of July, 41.7 percent of death row inmates across the United States are black, despite the fact just 12.7 percent of Americans are black. In a 2016 interview with The New Yorker, Mr. Stevenson noted Alabama until recently had dozens of monuments to the Confederacy and its leaders. Despite its celebration of the unsuccessful secession effort and its role in the civil rights struggle, his adopted home state displayed almost nothing commemorating the slaves and free blacks who suffered gross injustices. In 2018, he opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial, the first such monument “dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence,” recognizes the 4,000-plus individuals lynched by their fellow Americans. The museum focuses more broadly on racism and slavery in the United States. The memorial consists of more than 800 steel slabs, one for each county in the United States that saw a race-based lynching, with the names of victims inscribed on them. “The memorial is more than a static monument. In the six-acre park surrounding the memorial is a field of identical monuments, waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent,” its website states. “Over time, the national memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not. “EJI is inviting counties across the country to claim their monuments and install them in their permanent homes in the counties they represent. Eventually, this process will change the built environment of the Deep South and beyond to more honestly reflect our history.” (CN) – Native American voters in North Dakota will have an easier time at polling places after the state agreed to settle two tribes’ lawsuit over laws that restricted voters without proper identification.

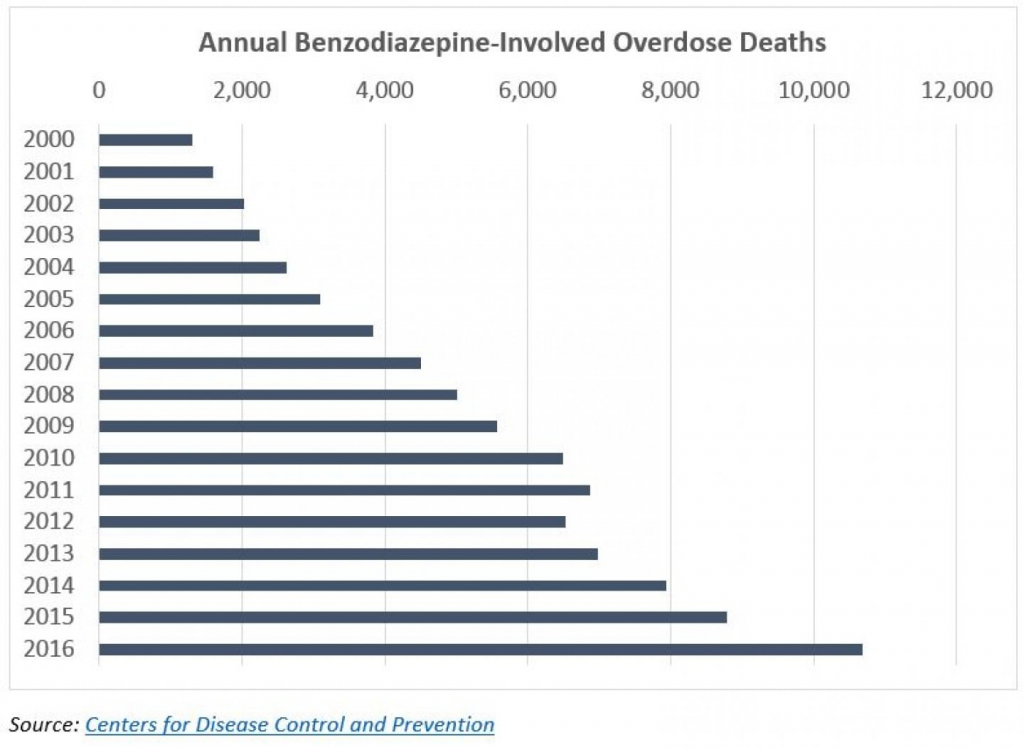

The state agreed to the settlement immediately following a federal judge’s decision to deny the state’s request to dismiss claims brought by the Spirit Lake Nation and Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. North Dakota is one of the least restrictive states in the U.S. on voting, as the sole state that does not require registration to cast a ballot in state and federal elections. However, the North Dakota voter ID law required voters to present valid identification listing a residential address. The tribes argued in their complaint that this law placed a heavy burden on Native American voters living on the reservation for several reasons, including homelessness and the state’s failure to assign residential addresses to some homes on reservations. The settlement requires North Dakota Secretary of State Al Jaeger to run a joint effort with the North Dakota Department of Transportation to distribute non-driver photo IDs on every reservation within 30 days of a statewide election. Jaeger’s office issued a joint statement under the settlement with the Spirit Lake and Standing Rock Sioux Tribes. “The consent decree will ensure all Native Americans who are qualified electors can vote, relieve certain burdens on the tribes related to determining residential street addresses for their tribal members and issuing tribal IDs, and ensure ongoing cooperation through mutual collaboration between the state and the tribes to address concerns or issues that may arise in the future,” the joint statement says. Both the plaintiffs’ legal counsel and Jaeger have signed and accepted the settlement. If the tribes agree, it will end the yearslong legal battles over the voter ID law. “This fight has been ongoing for over four years, and we are delighted to come to an agreement that protects native voters,” said Matthew Campbell, attorney for the Native American Rights Fund. “It has always been our goal to ensure that every native person in North Dakota has an equal opportunity to vote, and we have achieved that today. We thank the Spirit Lake Nation, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and the individual native voters that stood up for the right to vote.”  Despite overwhelming support from U.S. veterans, the U.S. government is not willing to support veterans with safer Cannabis based medical treatments despite increased cases of opioid addiction and suicide amongst U.S. troops and veterans. Medical cannabis helps millions of Americans treat a myriad of ailments – from cancer to fibromyalgia, as well as chronic pain and anxiety. For military veterans, the rigors, daily grind, physical excursion and long hours from years dedicated service take a toll on the human body, both physically and emotionally. There has been a lot of discussion and debate regarding medical cannabis among military veterans. In this article, we’ll discuss the VA’s stance on medical cannabis, its continued stigma, and whether it’s an effective treatment for PTSD. VA Medical Coverage for Cannabis The United States Department of Veterans Affairs, abbreviated as the VA, provides eligible veterans with healthcare coverage. At this time, cannabis medicine is not approved for former military personnel under their healthcare coverage provided by the VA. This is despite the fact that the vast majority of veterans appear to currently be in favor of medical cannabis. A poll conducted on behalf of the American Legion shows that 82 percent of respondents are in favor of legal medical cannabis, and 92 percent support further research on it, according to an article from Military Connection. A quick Google search will give you an abundance of scientific evidence that medicinal marijuana can be an effective treatment for pain management and PTSD – two of the main ailments suffered by veterans. Marijuana is an attractive alternative to patients who suffer from chronic pain, and millions of vets are no different. The opioid crisis is a hot button topic this election year, as it has been for some time now. According to the CDC, there were 47,600 deaths in the U.S. from opioids in 2017. There has never been a recorded death directly attributed to consuming cannabis. If any American deserves a replacement for potentially harmful pharmaceutical opioids like hydrocodone and tramadol, it’s servicewomen and men. Due to the current classification of cannabis as a schedule 1 drug, doctors cannot prescribe it to veterans. This classification also halts the much-needed research that must be done in order to expand access to the plant medicine. Each individual veteran is, of course, free to apply for medical herb, provided it’s legal in their home state. At the end of the Obama presidency, the DEA announced they were taking steps to approve access to medical marijuana research. This was in 2016, with a similar announcement being made in 2019. At the time of this writing, there hasn’t been any action taken by federal agencies like the DEA or FDA to make progress on these approved research licenses. The Stigma of Cannabis Treatment for PTSD PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, is a condition that is very common, impacting 3 million Americans for their own specific reasons. As much as 20 percent of Iraq war veterans currently suffer from PTSD. About 12 percent of Gulf War veterans suffer from PTSD, according to statistics from U.S. News. PTSD causes symptoms that can be hard for many veterans to cope with. These symptoms include emotional numbing, detachment, depersonalization, feeling like one is in a haze, and dissociative amnesia. One of the most common prescriptions for anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions that are associated with PTSD is a benzodiazepine called alprazolam, better known by its brand name Xanax. When combined with opioids like codeine, hydrocodone, which are also commonly prescribed to military vets, these rugs can cause serious side effects or even death. There were over 10,000 recorded deaths in the U.S. from benzodiazepines in 2016.drugs can cause serious side effects or even death. There were over 10,000 recorded deaths in the U.S. from benzodiazepines in 2016. For anyone, being cut off from drugs like Xanax is very dangerous and could even cause suicidal ideations in those who suffer from PTSD. As previously mentioned, a great alternative could be medical cannabis. There is an unfortunate stigma attached to medicinal marijuana treatments for PTSD and chronic pain, due to conflicting reports from mainstream news outlets and some anti-drug organizations. Some studies even claim that weed is abused by those with PTSD and chronic pain. There are other news stories that have reported cannabis is a promising and potentially effective treatment for PTSD. This scientific study concluded that the herb is associated with reductions in PTSD symptoms in patients accepted into New Mexico’s medical program. Most studies have been done on veterans consuming weed has been in the context of a drug abusive disorder, rather than it being a real treatment. The difficulty of researching the drug for PTSD was on display for ten years, as Dr. Sue Sisley led a team of researchers who were determined to finish the first clinical trial of cannabis consumption in veterans suffering from PTSD. Dr. Sisley was fired from her position at the University of Arizona because of the study, following complaints from a Senator. The stigma continues, with no clear end in sight – as a teacher in Florida could potentially lose his job due to him treating his PTSD with medicinal marijuana. The teacher’s name is Michael Hickman, a former Marine who served in Desert Storm. Hickman is fighting for his job, even though he was promoted to a dean. Hickman’s case certainly wasn’t the first instance of an employee being fired for consuming medical cannabis to treat PTSD, and it won’t be the last, either. It’s not difficult to find a plethora of news stories covering various cases like it. The Future of Medical Cannabis for Veterans The continued difficulty of much-needed cannabis research in the U.S. is no secret to anyone. Even Rolling Stone published a feature article on this. The reason why it’s so difficult to study it in the U.S. is that doing so requires approval from the DEA, the FDA, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Representatives from these agencies have reportedly drug their feet, with little progress being made. Many cannabis advocates, most notably those from NORML, point out this hypocrisy – as most federal lawmakers would lay claim that they support the military and its veterans. The few studies that are actually approved are only allowed to receive weed that is grown at The University Ole Miss, which reportedly supplies researchers will low-grade cannabis. As we move forward in 2020, hopefully, there will be progress made with more clinical trials and research, as cannabis prohibition and the lack of access to it is clearly damaging veterans suffering from PTSD. Legalization advocates would do well to support researchers and scientists like Dr. Sue Sisley, who subject themselves to the gauntlet that is gaining federal approval for cannabis research. About the author: Jason Sander is a versatile writer and marketer with fifteen years of experience serving clients. He couples this expertise with a passion for cannabis businesses and the science of medical marijuana. WASHINGTON — Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind was 22, eight months pregnant, and looking forward to her baby shower the following day when she went missing on a sunny August afternoon in 2017.

She had gone to a neighbor’s apartment in Fargo, N.D., where she had been asked to help with a sewing project. She never went home. Kayakers discovered her body floating in the Red River a week later. Police found her baby alive in the neighbor’s apartment. The neighbor was later convicted of murdering LaFontaine-Greywind and cutting the baby from her body. LaFontaine-Greywind was a member of the Spirit Lake Tribe; her mother is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. LaFontaine-Greywind is one of the thousands of Native American women missing or murdered in an epidemic of violence across the country. Indigenous women and girls face disproportionately high rates of violence in the United States. Experts estimate Native American women face a murder rate 10 times higher than the national average, with 84% experiencing some form of violence in their lifetimes, according to research from the National Institute for Justice, the research arm of the Department of Justice. So what’s the government doing about it? U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-Ariz.) recounted Savanna’s story at a hearing on the issue last year in the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee. Gallego paused to clear his throat, shook his head and blinked tears out of his eyes. “I know these stories are hard to hear, trust me, it’s hard for me to read them, but we must face this problem in order to address them,” Gallego said, his voice breaking. “We must improve the data system related to murdered and missing indigenous women to truly identify the scope of this problem.” Policymakers “must take action, so this does not keep on going,” Gallego added. After decades of grass-roots advocacy from indigenous activists and victims’ families, federal and state governments have recently begun to take action with task forces and legislation. One of those bills is named after LaFontaine-Greywind. Savanna’s Act, a rare bipartisan effort on Capitol Hill, calls for more federal and tribal coordination in response to cases of missing or murdered Native American women. Cataloging the crisis No one knows exactly how many Native women go missing or are murdered each year. There is no official federal database on the issue. But more than 5,600 cases for missing Native women or girls had been logged in the FBI’s National Crime Information Center database by the end of 2017. But those numbers don’t tell the whole story. Advocates say the overall numbers are likely higher, since some Native people do not report data to the federal government. Last year, only 47 of the 573 federally recognized tribes participated in the database, partly due to some tribes’ lack of access to updated computers or internet. Without data on all potential crimes, some cases go cold. Investigators at a crime scene or on traffic stops can’t pull up information on missing people or potential suspects. And even when they are reported, victims are sometimes misclassified or overlooked, especially if they live in urban areas instead of on reservations. On some reservations, indigenous women are murdered at more than 10 times the national average, according to the Indian Law Resource Center. A crisis with roots in ‘historical mistreatment’ Michigan has 51,804 people who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, according to the 2013-17 U.S. census American Community Survey Demographic And Housing Estimates. That’s .5% of Michigan’s population. About one-quarter of all murders of Native Americans in Michigan go unreported to the FBI, according to a study from the Murder Accountability Project, a nonprofit that examines unsolved murders. The study looked at data from the Centers for Disease Control and FBI from 1999 to 2017. There are varied and complicated forces at play behind the disproportionate violence and patchy response. Activists and researchers say the crisis has been building for years, a legacy of generations of injustice, including government policies forcing people from their land and sex trafficking of girls and women. Victims can be targeted because they live in remote areas or because of their race. Some are dealing with addiction or other trauma. “The crisis we are talking about has deep roots in the historical mistreatment of Native women,” Sarah Deer, a professor at the University of Kansas and citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma, told lawmakers at a hearing on the issue last spring. “Native women and girls have been disappearing literally since 1492, when Europeans kidnapped native women for shipment back to Europe,” she said. There are 573 federally recognized Indian tribes in the United States and approximately 326 Indian reservations. Over one million Native American residents live on or near reservation lands. Victims’ families can face a patchwork of tribal, state and federal law-enforcement agencies to respond to a crime, and sometimes victims are dismissed as chronic runaways. ‘Glaring holes’ in federal response As the issue has gained national attention, Congress and the White House have raced to show some response. President Donald Trump authorized a new federal task force on the issue last November. It met for the first time in January. The group’s aim is to develop protocols and procedures to address new and unsolved cases. The task force includes representatives from the Department of Interior, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Department of Justice and other federal agencies. “The task force is eager to get to work to address the issues that underlie this terrible problem, and work with our tribal partners to find solutions, raise awareness, and bring answers and justice to the grieving,” Attorney General William Barr said in a statement. But notably missing from the task force itself are tribal leaders or indigenous survivors -— a point of contention for indigenous advocates who have been tracking the issue for years. Annita Lucchesi, executive director of the Sovereign Bodies Institute, said the task force seems like a hollow attempt to make it appear the administration is addressing the issue in an election year. “It has glaring holes in terms of who should be there,” Lucchesi said. “Frankly, I don’t trust federal agencies to self-investigate and identify their own gaps and breakdowns in justice, and self-correct with no outside accountability.” Action in Congress? In the U.S. Capitol, lawmakers have introduced two significant stand-alone bills on the issue in recent years: Savanna’s Act and the “Not Invisible Act,” as well as provisions for Native women in the Violence Against Women Act. Lucchesi is more hopeful about the potential for those bills — which focus on better data collection. “You can’t end violence that you don’t understand,” Lucchesi said. Savanna’s Act would boost coordination between federal and tribal agencies and improve tribal access to law enforcement databases. Former U.S. Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-N.D.) first introduced Savanna’s Act in 2017. It passed the Senate unanimously, but faced a roadblock from Republicans who controlled the House of Representatives at the time. Former U.S. Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), then the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, blocked it in the House. He objected to how it dispersed federal funds. Since then, Goodlatte retired and Democrats took control of the House, opening the door for action on the bill this year. The senators also changed some language in the bill to try to overcome any opposition from the House. The “Not Invisible Act” would create a new federal post within the the Bureau of Indian Affairs to coordinate violent crime prevention. It also requires the Interior department and attorney general to form an advisory committee on violent crime. There are no Michigan House or Senate co-sponsors for Savanna’s Act. The Not Invisible Act is co-sponsored by U.S. Reps. Brenda Lawrence (D-Southfield) and Dan Kildee (D-Flint). Separate legislation passed by the U.S. House last year — a reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act — would require the Government Accountability Office to look at how law enforcement agencies are responding to the crisis. It also gives tribes more jurisdiction over crimes committed on tribal land and includes provisions to allow tribal law enforcement officers to prosecute non-tribal members for domestic violence on tribal land. The House approved the landmark VAWA last year, but it has made no progress in the Senate. The issue has also made its way into other legislation. Debate in the House this year over a massive infrastructure bill included discussion of the need for expanded broadband and 911 access, in part to help Native women. Researchers and advocates say these efforts are hopeful, but it will take years of work to reverse the problems. “There will be no quick fix to this problem. The crisis has been several hundred years in the making and will require sustained multi-year, multifaceted efforts to understand and address the problem,” said Deer of the University of Kansas. Can you believe we're in 2020, where you'll be able to major in weed at Colorado State University-Pueblo? It's true, with Denver Post reporting that the university just received approval for the Denver's first degree program focused on cannabis.

The program is called "Cannabis, Biology and Chemistry" and will see the course similar to double-majoring in biology and chemistry, while focusing on the science required to work in the world of cannabis, according to David Lehmpuhl, dean of CSU-Pueblo's College of Science and Mathematics. Lehmpuhl said: "It's a rigorous degree geared toward the increasing demand coming about because of the cannabis industry. Hemp and marijuana has really come to the forefront in a lot of economic sectors in the country. We're not pro-cannabis or anti-cannabis. What we're about will be the science and training students to look at that science". The course is split into two: natural products and analytical chemistry. Starting with the natural products, it will see students taking up additional courses in neurobiology, biochemistry and genetics. Students will also work in a lab setting to learn about the genetics of cannabis, and other natural product plants. Lehmpuhl added: "A lot of the products that people are selling from the cannabis plant, if they can be genetically produced, become more profitable". The second part of the course is the analytical chemistry option that will see students working with the chemical compounds of cannabis, trying to work out which cannabidiol, or CBD, concentration should be in a product. As for the lab itself, it is licensed to grow industrial help with students possibly working with CBD, but the lab itself will not have products with high levels of CBD -- which is the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana (you know, the part that makes you high). Lehmpuhl expects a high demand for the program. He added: "One of the things that motivated us to develop this program was this industry is sort of developed without oversight and regulation. I think now it's becoming clear when you look at even the recent vaping crisis that occurred that there's a need for having trained scientists in that space". By Anthony Garreffa Access v. Abuse: The ADA’s Impact in Silicon Valley

A San Jose father of three took his kids to their cousin’s 6th birthday party at a Chuck E. Cheese one afternoon a few weeks ago, but was stopped dead in his tracks the minute he entered the room. He watched as his kids excitedly ran up the stairs to greet their family members, their eyes hankering over the sight of pizza and arcade games awaiting them. But for 30-year-old wheelchair user David Tibbitts-Hernandez, there was no way for him to get up to the second floor to meet his kids. He scoured the room for an elevator or ramp but the restaurant didn’t have one, so he said goodbye to his kids — upset that he couldn’t stay — and turned back to go home. “I had to turn around and go back home and leave my kids there with their family,” Tibbitts-Hernandez told San José Spotlight in a recent interview. “As kids, they don’t necessarily understand.” Tibbitts-Hernandez’s experience speaks to the promise the Americans with Disabilities Act said it would provide nearly 30 years ago, demonstrating the barriers disabled individuals continue to face in public spaces. But for most Americans, those barriers often go unseen — performing regular activities such as opening a heavy door, dropping off a package or entering a building do not cross their minds. Though for millions of disabled people who perform these ordinary acts daily, there’s always the risk that a simple task can turn into an anxiety-inducing nightmare. The actions most people take for granted, he said, is what the disabled community often experiences challenges with every day, on top of the social stigmas they continue to face. The law, though well-intended, seems to have unintended impacts for both the people it was meant to help — such as Tibbitts-Hernandez — and small businesses that find themselves in the crosshairs of serial ADA lawsuits that force their closure, such as Crema Coffee, as first reported by San José Spotlight last week. “The people who are ‘violating the law’ don’t really know in most cases when they’re innocent, and they don’t have a ready ability to defend themselves, but being innocent isn’t an excuse,” said federal defense attorney Richard M. Hunt, who has specialized against ADA lawsuits for 15 years. “For small businesses, even if they think they could win the lawsuit they can’t afford it and that’s really how the law is getting exploited.” After 26 years, Tibbitts-Hernandez started using a wheelchair when his multiple sclerosis made it too difficult to walk. The transition took a toll on him and his family, as he relearned how to carry out simple tasks. It’s frustrating to lose one’s autonomy, he added, when a barrier or lack of access means having to ask strangers to reach for items that are too high on a grocery shelf or not even being able to comfortably use a public restroom. But the change also opened his eyes to all of the small challenges that disabled individuals are faced with daily. “Things became more difficult and everything had to be planned out ahead of time. Just going anywhere I have to know what the front of the place looks like, where I’m going to get into the door, or if the bathrooms are accessible,” Tibbitts-Hernandez said. “There’s a lot of places that I used to go to and enjoy but I can’t necessarily go to anymore. So when (businesses) don’t even care to make it accessible, it’s just discouraging.” History of ADA At least 55 million people in the U.S. have a severe disability that impairs their ability to perform functional tasks or prevents them from walking, talking, seeing or hearing, according to U.S. Census data. In California alone, the Center for Disease Control reported that a quarter of the state’s population has some type of disability. But for years, nothing secured the rights of disabled individuals, which meant that exclusion from schools, denied work opportunities and unaccommodating public transit services were all common occurrences. Disability rights activists long fought to secure equal rights to access, going as far as crawling their way up to the nation’s Capitol to make their case in the spring of 1990, physically pulling themselves up each step on their bare hands and knees. The famous event, dubbed the Capitol Crawl, was the catalyst that eventually pushed lawmakers to finally enact the ADA. Now, nearly three decades later, the ADA — a monumental civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against the disabled — has secured and upheld the rights of a minority group that would otherwise not receive the same kinds of access or opportunities as most people. Yet many businesses across California — and here in the heart of Silicon Valley — don’t do enough to make the disabled community feel welcome when a barrier or obstacle prevents them from entering or moving around in a public space, Tibbitts-Hernandez and others said, forcing them to stay home or meticulously plan an outing. Addressing serial litigators Unlike some disabled wheelchair users though, Tibbitts-Hernandez doesn’t want to sue, and according to Sheri Burns, the executive director for the Silicon Valley Independent Living Center, that’s not at the forefront of most disabled residents’ minds. It is only a handful of serial litigants and their unscrupulous attorneys who file thousands of ADA lawsuits in California against small businesses, some they haven’t even visited, in what critics call a “shake down” for minor violations. “Most people with disabilities are not interested in creating problems for other people. They want to be able to enjoy the access to the same public areas that everybody else does,” Burns said, adding that disabled residents’ biggest concern is being accommodated. In California, businesses getting slammed with ADA lawsuits are left to fend for themselves when serial complaint filers take advantage of the ADA and its state counterpart, the Unruh Civil Rights Act, and sue thousands of small businesses at once. For many of these attorneys, the hundreds of lawsuits they file prove to be a lucrative business, but often force mom and pop shops to close, as many owners can’t afford to bring their businesses up to code or settle. These two clashing realities have heart-wrenchingly twisted the conversation on ADA compliance, pitting small businesses and disability rights groups against one another in a moral impasse over fairness and principles. California accounts for nearly 40 percent of the country’s ADA lawsuits, according to the state’s Chamber of Commerce. Still, many disabled individuals fiercely dismiss claims that businesses can’t comply with the federal law for one reason or another, as plenty of time has passed for these owners to come to terms with its requirements. “They need to figure it out,” said Santa Clara resident Frances Merrill, 59, a wheelchair user born with cerebral palsy. “I know it can be hard financially… but that just means they’re not willing to think outside the box. The ADA has been around for 30 years. If you haven’t figured it out yet… it just makes people feel like you don’t want to.” And not complying with the law goes against an individual’s civil rights — comparable to racial discrimination, said Burns, who agrees more should be done about small businesses being hit with “drive by” lawsuits, but not at the expense of the disabled community. “Unscrupulous attorneys have made a good business bringing lawsuits, and this has been going on for quite a while,” Burns said. “So we’ve got to engage the local governments in the states to get involved in coming up with real solutions that don’t impact the civil rights of people.” Contact Nadia Lopez at nadia@sanjosespotlight.com or follow @n_llopez on Twitter. August 18, 2020 marks 100 years because the ratification of the 19th Modification making sure all American ladies “suffrage,” or the precise to vote. The dominant narrative in regards to the ladies’s suffrage motion is framed during the studies of white ladies (and to some degree, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, a famous and outspoken supporter of girls’s rights). However African-American ladies performed a big position in acquiring the precise to vote even supposing lots of them would no longer really experience the precise themselves to the similar extent till a long time later. In 1872, Susan B. Anthony tried to vote within the presidential election and was once arrested and attempted in Rochester, New York. In Combat Creek, Michigan, Sojourner Fact demanded a poll and was once grew to become away. The suffrage motion was once in complete swing. Ladies’s rights activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Betsy Ross, who championed gender fairness, did not really feel the similar about race. Whilst many white suffragists labored to assist remove the establishment of slavery, they didn’t paintings to make sure that former slaves would have citizenship or balloting rights. “Black ladies weren’t accounted for in white ladies’s push for suffrage. Their struggle wasn’t about ladies writ massive. It was once about white ladies acquiring energy – the similar energy as their husbands, black ladies and black males be damned,” says Howard College Assistant Professor Jennifer D. Williams. Stanton and Ross and different high-profile leaders within the motion did not improve the 14th and 15th amendments, which granted former slaves citizenship rights and gave black males balloting rights. Given this chasm, a black ladies’s suffrage motion advanced along the mainstream motion. “There was once a concerted effort via white ladies suffragists to create obstacles in opposition to black ladies operating within the motion,” says historian and writer Michelle Duster. “White ladies had been extra eager about having the similar energy as their husbands, whilst black ladies noticed the vote as a way to making improvements to their prerequisites.” SOME BLACK SUFFRAGISTS YOU SHOULD KNOW Sojourner Truth (About 1797-1883) Born into slavery as Isabella Baumfree, she gained her freedom in the 1820s and supported herself through menial jobs and selling a book written by Olive Gilbert, “Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Northern Slave, Emancipated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York in 1828. At the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention held in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth delivered what is now recognized as one of the most famous abolitionist and women’s rights speeches in American history, “Ain’t I a Woman?” In 1872, Truth was turned away when trying to vote in the U.S. presidential election in Battle Creek, Michigan. Harriet Tubman (About 1820-1913) Tubman, whose birth name was Araminta Ross, is commonly known as an emancipator who led hundreds of slaves to freedom along the underground railroad. She also was a staunch supporter of women’s suffrage, giving speeches about her experiences as a woman slave at various anti-slavery conventions, out of which the voting rights movement emerged. Coralie Franklin Cook (1861-1942) Cook founded the National Association of Colored Women and was known as a committed suffragist. In 1915, she published “Votes for Mothers” in the NAACP magazine The Crisis discussing the challenges of being a mother and why women need the vote. Angelina Welde Grimke (1880-1958) A well-known feminist in the District of Columbia, Grimke was a journalist, playwright, poet, lesbian, suffragist and teacher. Grimke wrote for several journals such as Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review. Educated at Wellesley College, Grimke’s literary works exposed her ideas about the pain and violence in black women’s lives, and her rejection of the double standards imposed on women. Charlotta (Lottie) Rollin (1849-unknown) After the Civil War, the woman suffrage movement split into two separate organizations: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) —a more radical group and the more mainstream American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Rollin joined the AWSA. During Reconstruction, Rollin became active in South Carolina politics working for congressman Robert Brown Elliott. Rollin spoke on the floor of the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1869 in support of universal suffrage. By 1870, Rollin chaired the founding meeting of the South Carolina Woman’s Rights Association and was elected secretary. Several of Rollin’s family members — sisters Frances, Kate and Louisa also were active in promoting women’s suffrage at both the state and national levels. Mary Ann Shad Cary (1823-1893) Cary was perhaps the first black suffragist to form a suffrage association. During the 1850s, she was a leader and spokesperson among the African American refugees who fled to Canada after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. In 1853, she founded the Provincial Freeman, a newspaper dedicated to the interests of Blacks in Canada. Cary spoke at the 1878 convention of the NWSA applying the principles of the 14th and 15th Amendments to women and men. She called for an amendment to strike the word “male” from the Constitution. In 1871, Cary unsuccessfully tried to vote in Washington, but she and 63 other women prevailed upon officials to sign affidavits attesting that women had tried to vote. In 1880, she organized the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise Association, which promoted suffrage and educated people on finance and politics. Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855–1948) A journalist, Mossell, wrote a women’s column in T. Thomas Fortune’s newspaper, The New York Freeman. Her first article, “Woman Suffrage” published in 1885, encouraged women to read suffrage history and articles on women’s rights. Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) Wells, who worked with white suffragists in Illinois, founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first suffrage group for black women. They canvassed neighborhoods and educated people on causes and candidates helping to elect Chicago’s first black alderman. In 1913, Wells and some white activists from the Illinois delegation traveled to Washington to participate in the historic suffrage parade where women gathered to call for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. Black suffragists were initially rejected from the event. Wells and other suffragists including white suffragists like Stanton wrote letters asking the parade to allow black women to participate. Event leaders acquiesced, requiring black suffragists to march in the back of the parade to assuage the feelings of white women in the movement who did not want them there. Despite the conditions, black suffragists participated. However, Wells refused to march at the back. Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954) In 1896, Terrell and fellow activists founded the National Association of Colored Women and Terrell served as the association’s first president. After the passage of the 19th Amendment, Terrell turned her attention to civil rights. Anna Julia Cooper (1858-1964) Anna Julia Cooper was a prominent African American scholar and a strong supporter of suffrage through her teaching, writings and speeches. Cooper worked to convince black women that they required the ballot to counter the belief that ‘black men’s’ experiences and needs were the same as theirs. Rosa Parks (1913-2005) Known as the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” because of her role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Parks continued to work for civil rights which included voting rights. Parks served as an aide to Congressman John Conyers and used her platform to discuss many issues, including voting rights. Charlotte Vandine Forten (1785 –1884) An abolitionist and suffragist, Forten came to Washington in the late 1870’s with her husband, James Forten, a wealthy sail maker and abolitionist. She was a founder and member of the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, many of whose members became active in the women’s rights movement. Harriet Forten Purvis (1810 – 1875) Daughter of wealthy sailmaker and abolitionist reformer James Forten and Charlotte Forten, Forten Purvis and her sisters were founding members of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, and members of the American Equal Rights Association, where Harriet served as a member of the executive committee. Affluent and educated, the sisters helped lay the groundwork for the first National Woman’s Rights Convention in October 1854 and helped organize the Philadelphia Suffrage Association in 1866. Margaretta Forten (1806 -1875) Forten was an educator and abolitionist. She and her mother, Charlotte Forten and her sister, Harriet, were founders and members of the interracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Harriet “Hattie” Purvis (1810-1875) A niece of the Forten family of reformers, Purvis was active in the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association and a member of their executive committee. Between 1883 and 1900, she served as a delegate to the National Woman Suffrage Association. She also served as Superintendent of Work among Colored People for the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, championing reforms. Sarah Remond (1826-1887) Remond was an antislavery lecturer and physician. The Remonds were a noted abolitionist family, well known in antislavery circles and, as a child, Sarah had attended abolitionist meetings. She was an activist in the Salem and Massachusetts Antislavery Societies, and a member of the American Equal Rights Association, where she served as a guest lecturer, and toured the Northeast campaigning for universal suffrage. Discouraged by the split in the women’s suffrage movement after the Civil War, she left the United States, becoming an expatriate in Florence, Italy, in 1866, where she studied medicine. Francis Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was an early abolitionist and women’s suffrage leader. She was one of the few African American women present at conferences and meetings about these issues between 1854 and 1890. She also wrote protest poetry that referenced which included musings about voting rights. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842 –1924) Ruffin was a Massachusetts journalist and noted abolitionist before the Civil War. She joined the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association in 1875 and was affiliated with the American Woman Suffrage Association. She was a black woman’s club leader in Massachusetts and the wife of George L. Ruffin, one of the woman’s suffrage representatives from Boston in the state legislature. She challenged the opposition to woman’s suffrage in Boston, writing an editorial co-authored with her daughter, Florida Ridley. Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879-1961) Burroughs, an educator, church leader and suffrage supporter, devoted her life to empowering black women. She helped establish the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 and founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1909. Ella Baker (1903-1986) Civil rights activist and freedom fighter, Ella Baker played a key role in some of the most influential organizations of the time, including the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In 1964, SNCC helped create Freedom Summer, an effort to both focus national attention on Mississippi’s racism and to register black voters. Baker and many of her contemporaries believed that voting was one key to freedom. Nsenga K. Burton is an award-winning professor, multimedia journalist, filmmaker and producer. She is co-director of the Film and Media Management concentration at Emory University in the Department of Film and Media Studies, where she teaches courses on Hollywood’s entertainment industries, content creation and special topics like Reality Television and Hip-Hop Media. Follow her on Twitter @Ntellectual. When a wrongful conviction is the result of prosecutorial misconduct, the prosecutor and other authorities involved in the case are less likely to spend time or energy finding the perpetrators of the original crime.

The troubling conclusion, based on a study of exonerations published in the Crime & Delinquency journal, suggests that misbehavior or incompetence of the system’s most powerful players can perpetrate a double injustice: it not only sends an innocent individual to prison, but poses a “substantial threat to the public” by allowing the real criminal to, often literally, get away with murder. The author of the study, Jennifer N. Weintraub, a Pd.D. candidate in criminal justice at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany, examined 335 DNA exonerations, focusing on 86 cases where prosecutorial misconduct—such as failure to provide exculpatory evidence to defense attorneys—was either alleged or proven. She concluded that in such cases, it was 59 percent less likely that the true perpetrators of the crimes for which the wrong person had been convicted would be found. “Only 33 DNA exoneration cases in which prosecutorial misconduct was a contributor in the wrongful convictions identified a true perpetrator, compared with 80 percent of cases without such misconduct that did identify a true perpetrator, “ Weintraub wrote. DNA exonerations are one subset of wrongful conviction cases. In about two-thirds of all exoneration cases, according to research cited by Weintraub, the guilty individuals escaped punishment. Without DNA evidence, findings of innocence depend on the defendant being able to hire an attorney willing to follow up leads to identify the guilty person. At the same time, research has shown that investigative flaws, omissions or willful distortions of the evidence by prosecutors and other players in the system are present in over half of wrongful conviction cases, and in 79 percent of homicide exonerations, Weintraub wrote. Weintraub said her research demonstrates that prosecutorial misconduct “can obstruct the postconviction procurement of compelling evidence, which would favor the wrongfully convicted and hinder a true prosecutor.” According to Weintraub, her findings should encourage the development of better “mechanisms” by state authorities and bar associations to address and deter prosecutorial misconduct, citing for example legislation passed last year in New York State to create a state body empowered to investigate complaints of misconduct brought by any citizen. Editor’s Note: In January a New York judge struck down the legislation establishing the commission on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. But the study offered no legislative remedy that would compel a prosecutor to reopen an investigation into a case in the absence of any new evidence, other than public or media pressure. The reasons why prosecutors balk at helping identify the real culprits, even after their original case was thrown out, range from professional pride and the fear of being seen as ”soft on crime” to the loss of original documents or evidence, Weintraub said. The damage, however, to the public, which has been “lulled into a false sense of security,” is arguably as serious as the impact on an innocent person who has wrongly spent years of his or her life behind bars, she charged. “The commission of prosecutorial misconduct can carry dangerous consequences that extend past wrongful convictions and into public safety,” Weintraub wrote. The full study is available for purchase here. TRENTON – Governor Phil Murphy today signed legislation (S1963) mandating comprehensive disclosure and transparency requirements for the system of civil asset forfeiture.

“New Jersey law enforcement agencies currently have no permanent statutory requirement to disclose civil asset forfeitures,” said Governor Murphy. “This legislation would boost confidence in our justice system by requiring county prosecutors to track and report data on this practice. Allowing the public to understand how assets are being seized, where seized funds go, and where forfeited property is going is a huge step forward for transparency and accountability.” Under the bill, county prosecutors would submit quarterly reports to the Attorney General detailing seizure and forfeiture activities by law enforcement agencies within their county. S1963 would also require specifying the law enforcement agency involved in a confiscation; date, description, and details of a seizure; the amount of funds or estimated value of a property; the alleged criminal offense associated with a seizure; and whether the defendant was charged with an offense and if those charges were ultimately dismissed or the defendant was acquitted, among other information. Using this data, the Attorney General would be required to create an online searchable database of civil asset forfeitures across New Jersey. Law enforcement agencies that fail to comply with the mandate would be required to return seized property or proceeds resulting from forfeited property. “As of right now, New Jersey has no reporting requirements for law enforcement agencies regarding property seizures, which has resulted in lacking transparency and protections for property owners,” said Assemblywoman Angela McKnight. “With this law the people of New Jersey and our state officials will finally have access to much needed data concerning which agencies are profiting from property seizures, what is being taken, and how the proceeds are being used.” “Everyone – law enforcement, watchdog groups, and, most importantly, our residents – benefits from the confidence and accountability that transparency provides,” said Assemblyman Jay Webber. “The only way we ultimately can police the process of asset forfeiture is through honest and comprehensive tracking, reporting, and public accessibility of the facts of forfeiture. This legislation will make New Jersey a national leader in asset forfeiture transparency.” “It’s un-American to take people’s property under the premise that it was gained through criminal activity when a person has not been convicted of a crime,” said Assemblyman Erik Peterson. “When homes, cars, money, and other property worth millions of dollars are seized every year, there must be adequate controls in place to prevent abuses. There’s no uniform seizure policy across the state making the reporting in this bill necessary. It shines a light on who is taking assets and ensures the money is used benefit taxpayers.” “Civil forfeiture has an extremely high potential for abuse, and it’s nearly impossible to challenge – and yet it remains one of the most opaque practices in law enforcement. Now, New Jersey takes the important step of shining a light on civil asset forfeiture through increased transparency and reporting, which we hope will be the first step among many to curb its use and rein in the harms it inflicts. This law moves our state closer to curtailing and ultimately ending the use of civil forfeiture and the racially disparate over-policing it encourages, disproportionately occurring in communities that are already some of New Jersey’s most vulnerable. We applaud Gov. Murphy for signing this law, and we commend the Legislature for passing it,” said ACLU-NJ Policy Director Sarah Fajardo. “We applaud Governor Murphy and the legislature on taking this step toward reforming civil asset forfeiture in New Jersey," said Tony Howley, State Director of the Americans for Prosperity and AFP Foundation. "We look forward to continue working with a broad coalition of organizations to further ensure that our liberties, private property, and civil rights are protected.” “We believe the Civil Asset Forfeiture bill signed by Governor Murphy today takes steps toward achieving a goal of fairness and equal justice in civil asset forfeiture proceedings, particularly for those with low income and limited means – who are unfortunately vulnerable and the hardest hit by these laws,” said Akil Roper, Vice President and Assistant General Counsel Legal Services of New Jersey. “The loss of property can disrupt employment, healthcare, family and other obligations and personal freedom. Disproportionate impact on racial minorities is also likely, given the higher rates of arrest for persons of color and its frequent employ in urban areas. Asset forfeiture litigants often have to go unrepresented, navigating a complex civil legal system which requires filing formal answers with costly fees, submitting evidence and making legal arguments." “By itself, improved transparency cannot fix the fundamental problems with civil forfeiture—namely, the property rights abuses it permits and the temptation it creates to police for profit,” said Jennifer McDonald, Senior Research Analyst at the Institute for Justice. “This bill is vitally important for bringing forfeiture activity and spending into the light of day and an important first step on the road towards comprehensive forfeiture reform.” With today’s signing, New Jersey becomes the 34th state in the nation to pass civil asset forfeiture reform and the 24th state specifically instituting disclosure and transparency requirements. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed