|

In the past 20 years, prosecutors in Conviction Integrity Units (CIUs) have increasingly taken on the responsibility of exonerating individuals who have been wrongfully convicted. Many of them collaborate closely with defense attorneys on case reinvestigation and resolution, exonerating defendants who otherwise had few remaining options. While the recent popularity of CIUs is an exciting development for the wrongfully convicted and their advocates, these newfound developments are not without risks. Prosecutors still hold the decision-making power. They choose which cases to review, and when and how to grant relief. And in cases where prosecutorial misconduct is a factor, those allegations are at risk of being ignored. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, district attorneys’ offices in nearly 100 different, mostly urban, jurisdictions have launched CIUs to formally review wrongful conviction claims. The recent popularity of the CIUs also suggests a cultural shift in the prosecutorial mindset—from tough on crime to smart on crime—that has likely influenced individual prosecutors in smaller jurisdictions as well. I studied prosecutors’ assistance with exoneration cases—both in the context of the Conviction Integrity Unit, and outside of it. My recent research relies on interviews with prosecutors and defense attorneys from 36 different jurisdictions. Several of them explained that prosecutors may make their cooperation with an exoneration in certain cases contingent upon defense attorneys dropping allegations of prosecutorial misconduct. In other cases, the defense attorney may voluntarily drop such allegations to improve their client’s chance of success. Prosecutors have been found to be less likely to assist with an exoneration if there is an underlying misconduct claim. There are notable exceptions. Some CIUs have launched reinvestigations into cases involving discredited police officers—such as in Cook County, Chicago, or Kings County, Brooklyn. Prosecutors have proactively exonerated individuals in such cases since the Los Angeles Rampart scandal of 1999 and 2000. Cases involving the publicized misconduct of officers who were subject to a federal investigation have produced hundreds of exonerations. Prosecutors reliably respond to these types of claims. Wrongful conviction claims at risk of being ignored—or sanitized of misconduct—generally involve allegations of prosecutorial misconduct. The National Registry of Exonerations estimates that 30 percent of exoneration cases feature prosecutorial misconduct. Pursuing Brady Violations A Brady violation, after the U.S. Supreme Court case of Brady v. Maryland, is one of the more common post-conviction misconduct allegations. Prosecutors commit Brady violations when they intentionally or unintentionally withhold evidence that could prove favorable to the defense. During reinvestigation, as files are re-opened and witnesses re-interviewed, this type of misconduct may come to light. Even well-intentioned prosecutors may have trouble recognizing it as a serious issue. A wealth of research into cognitive biases shows how conformity effects challenge a person’s willingness to act against the group status quo. For this very reason, some progressive prosecutors try to insulate their CIU from the rest of the office. They may hire a CIU chief from outside the office, (preferably a person with defense experience), or even an attorney from an innocence organization. They may also ensure that the CIU chief reports directly to them, rather than to a deputy DA already embedded in the office. So-called professional exonerators, who work through formal wrongful conviction review entities like a CIU or an innocence organization, can better establish ongoing rules of engagement. A recent report from the Quattrone Center on the Fair Administration of Jujstice at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School provides comprehensive guidelines for “collaboration agreements” that outline how to handle discovery of misconduct and other delicate issues like media relationships and information sharing. However, not all CIUs have embraced this model, and not all prosecutors assisting with exonerations work in a CIU. Smaller prosecutors’ offices will not have the staff or funding for a standing CIU. Prosecutors in smaller jurisdictions may have never worked with an innocence organization before, or reinvestigated a wrongful conviction case. My recent research suggests that prosecutors and defense attorneys who are not professional exonerators are more likely to engage in post-conviction bargaining such as agreeing to forego litigation around negligence or misconduct. Holding Bad Actors Accountable In the short term, overlooking the misconduct could result in a quicker exoneration. In the long term, it could complicate the exoneree’s chances in a lawsuit, foreclose the opportunity to investigate similar cases, and fail to hold the bad actor accountable. Therefore, State Attorneys General or State Commissions should fill in the gaps. The North Carolina Innocence Inquiry Commission, created after a high-profile case of prosecutorial misconduct in 2006, has since helped secure 15 exonerations. Leaving this work to individual prosecutors in a patchwork of practices throughout the state may result in post-conviction agreements that harm the defendant’s chance of exoneration, or their success in a lawsuit. At a minimum, those who advocate for the wrongfully convicted can continue to demand transparency by ensuring their local CIU has a collaboration agreement in place and by encouraging partners in smaller jurisdictions to adopt this practice as well. Prosecutors are accepting greater responsibility to correct wrongful convictions, but it remains to be seen if they can also accept greater responsibility for the misconduct that contributes to them. Exonerations represent an important opportunity to address failures in the criminal justice system. Failure to confront misconduct allegations risks fostering a climate where misconduct will continue to be tolerated, leading to more wrongful convictions. Elizabeth Webster, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Loyola University in Chicago. She has previously published in scholarly journals such as Justice Quarterly and the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology

0 Comments

A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has found that nearly 108,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2021, a record level that is up 15 percent from those counted in 2020, which was already 30 percent higher than pre-pandemic estimates in 2019, reports the Courthouse News Service. Dr. Rahul Gupta, the director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said in a statement that a proposed $41 billion plan to tackle the overdose epidemic will expand access to high impact harm reduction tools like naloxone, quickly connect more people to treatment, and disrupting drug trafficking operations. Meanwhile, Axios reports that drugs for treating opioid abuse aren’t reaching most high-risk patients, potentially widening gaps in care as overdose deaths hit record highs. Nearly 53 percent of patients with opioid use disorder were not prescribed buprenorphine, which reduces the risk of future overdoses, according to a new analysis of insurance claims from about 180,000 people. More than 70 percent of opioid users who also misuse other substances, such as alcohol or methamphetamine, weren’t prescribed the drug. In 2021, roughly 71,000 Americans overdosed on fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. The report also accounts for overdose deaths from cocaine, methamphetamine and other drugs. Overdose deaths for cocaine and meth, respectively, went up by 23% and 34% from the previous year in 2021. According to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, America’s opioid epidemic has worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic — which made it more difficult for drug addicts to get access to treatment during lockdowns. “Motherhood and Pregnancy Behind Bars.” Incarceration is “uniquely detrimental” to women, particularly if they are mothers, and authorities should consider alternative approaches to punishment for them, says a Texas justice advocacy group. “With a fraction of the money it costs to incarcerate a mother, we can support her with tools to address underlying needs, as well as keep her with her children and in the community –in turn preventing trauma and loss for the entire family unit,” argued the Texas Center for Justice and Equity, in a special report on “Motherhood and Pregnancy Behind Bars.” The report, released this week, focused on what it said was unequal and often cruel treatment for mothers in Texas jails and prisons. Despite the passage of several state laws aimed at improving conditions, Texas reflected the national failure to address the long-term generational harms caused by “locking up motherhood,” researchers wrote. “When we incarcerate women – the majority of whom are mothers – we are not only failing them but failing our children and our communities,” the report said. “We are leaving unaddressed the issues that drive women into incarceration: poverty, educational inequality, trauma and mental health issues, (and) substance use.” The U..S. imprisons about 30 percent of the global incarcerated female population—approximately 215,000 women—despite having just four percent of the world’s female population, according to figures cited in the study. Black and brown women are disproportionately represented in U.S. prison and jail populations—about 23 percent—in effect “perpetuating ruthless cycles of incarceration that have an oversized impact on communities and generations of color,” the study said. Research has also shown that the female incarceration rate in the U.S. is growing at a faster rate than men. Other research has shown that the primary driver of higher female incarceration rates is prosecution for non-violent drug charges, either possession or trafficking. Advocates have said that ending the punitive approach fueled by the War on Drugs would help reduce prison populations overall. Pregnant Behind Bars The researchers devoted special attention to the conditions faced by women incarcerated in Texas facilities who are pregnant and give birth while in custody. More than 8,700 females were behind bars in Texas as of February 2022, and between 5 and 10 percent of them were pregnant when they entered prison, the study said. Some 110 women gave birth in Texas custodial facilities during 2020. Once in custody, they were less likely to receive proper medical care for their pregnancies and were “more likely to have complications in birth that lead to cesareans and have babies born at a low birthweight,” the study said. Interviews with formerly incarcerees revealed that post-partum care was also inadequate; some mothers were separated from their infants as early as three days after giving birth. Most must surrender their newborns within hours or days. Additionally, many facilities heavily limit the physical access that women have with their children during visitations, including through “militarized patrolling of visitation rooms, which can affect postpartum depression and bonding with their children.” The lack of care extends as well to mothers of young children. Visitations are often limited to video screens. “I remember just looking at this fuzzy screen and crying,” the daughter of one female incarceree recalled in an interview with researchers. “My mom was trying to console me, but she couldn’t even wipe the tears from my eyes.” Researchers were told that one woman in an unidentified Texas prison was placed in solitary confinement after giving birth “for crying because her baby was taken from her at the hospital, while she was returned to the prison unit.” The study noted that Texas legislators had approved new legislation in 2018 and 2019 that required state corrections authorities to improve nutrition for pregnant women and expand access to educational and vocational training, and mental health counseling. Another bill, passed in 2021, allowed formerly incarcerated women to petition for reinstatement of parental rights, ending a situation in which some mothers were permanently prohibited from access to their children based on the nature of their original offenses. But “confidential reports made by incarcerated women to the Texas Center for Justice and Equity show that practice often looks different than policy.” Recommendations The study outlined a set of recommendations, aimed at persuading authorities to “rethink” the treatment of incarcerated women—foremost among them avoiding incarceration altogether when feasible. Authorities should “take real, viable steps to keep women out of incarceration altogether – including by removing funding from harmful carceral systems,” the study said. The recommendations included:

These policy changes were essential not just for ameliorating the conditions of individual women, but for the health of the community, the study said. “When a mother is locked up, it’s never just one person who suffers,” said Cynthia Simons, one of the study authors. “The violence of incarceration ripples through generations, whether through poor prenatal care for pregnant women behind bars, family separation soon after a baby’s birth, or the negative impact of trauma on kids whose parents are incarcerated.” Noting that statistics showed two-thirds of incarcerated mothers were primary caregivers to young children, the authors said better treatment inside prison was crucial to the development and nurturing of healthy young adults. “Motherhood must be uplifted and held in the highest regard,” the study said. “For the sake of our children, families and communities, we must stop locking it up.” The principal authors of the study were Cynthia Simons and Chloe Craig. Editor’s Note: The Texas Center for Justice & Equity was formerly known as The Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. In recent years, legal scholars have advanced powerful critiques of mass incarceration. Academics have indicted America’s prison system for entrenching racism and exacerbating economic inequality. Scholars have said much less about the law that governs penal institutions. Yet prisons are filled with law, and prison doctrine is in a state of disarray. This Article centers prison law in debates about the failures of American criminal justice. Bringing together disparate lines of doctrine, prison memoirs, and historical sources, we trace prison law’s emergence as a discrete field — a subspeciality of constitutional law and a neglected part of the discipline called criminal procedure. We then offer a panoramic critique of the field, arguing that prison law is predicated on myths about the nature of prison life, the content of prisoners’ rights, and the purpose of penal institutions. To explore this problem, we focus on four concepts that shape constitutional prison cases: violence, literacy, privacy, and rehabilitation. We show how these concepts shift across lines of cases in ways that prevent prison law from holding together as a defensible body of thought. Exposing the myths that animate prison law yields broader insights about judicial regulation of prisons. This Article explains how outdated tropes have narrowed prisoners’ rights and promoted the country’s dependence on penal institutions. It links prison myths to the field’s central doctrine, which encourages selective generalizations and oversimplifies the difficult constitutional questions raised by imprisonment. And it argues that courts must abandon that doctrine — and attend to the realities of prison — to develop a more coherent theory of prisoners’ constitutional rights. It is a pity indeed that the judge who puts a man in the penitentiary does not know what a penitentiary is. I spent much of my early childhood touring the various residential congregate care facilities where my older brother spent ages 10 to 14. I became used to fawning at the residential treatment counselors for treats and scavenging old toys that the clients forgot. Above all, I refrained from seeking emotional help from parents, teachers, or doctors, lest I get spirited away to a facility, the way my brother and others in my community did.

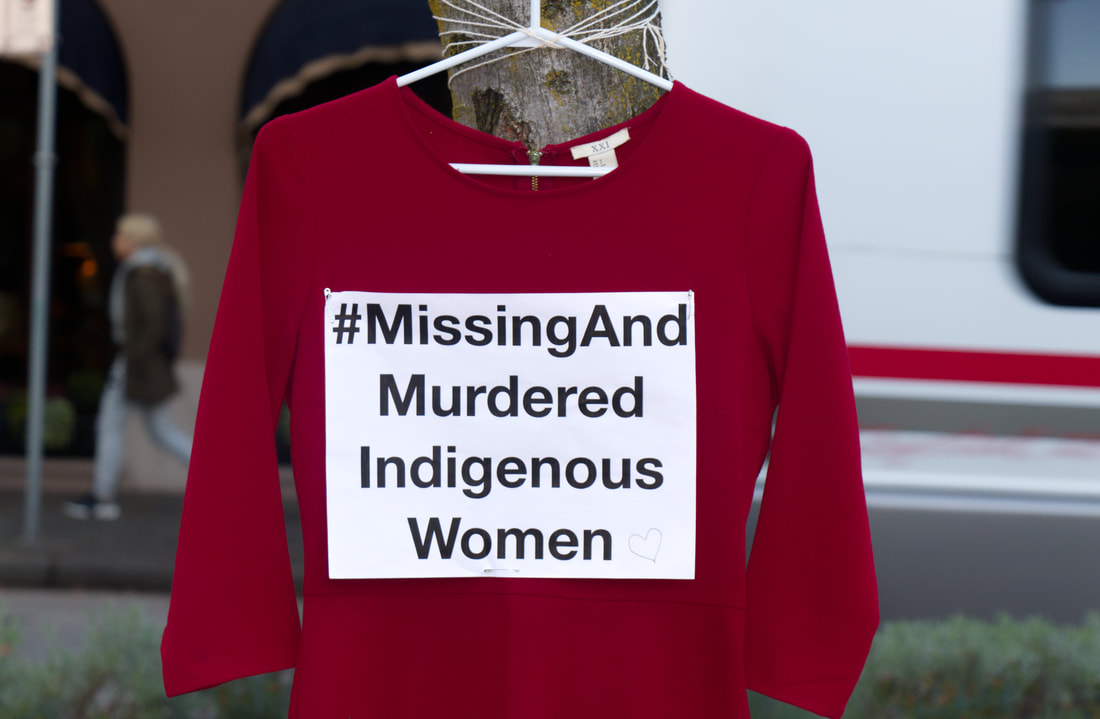

The threat of being removed from my home was ever-present for me and my friends. Speaking up would leave us vulnerable to entering the child welfare or juvenile detention systems. This phenomenon of whisking kids away from their communities, often for random offenses or emotional difficulties like truancy or self-harm, can prime youth for the prison system. While a lot has changed in child welfare since I was a child, in 2017 a study found that 37.4 percent of U.S. children will have a child welfare involvement by their 18th birthday. For Black kids, the lifetime risk of child welfare involvement increases to over 50 percent. Throughout the ‘90s and the 2000s, federal investigations, whistleblowers, and research revealed massive shortcomings in the handling of young people in these institutions, from excessive and forced medication to abuse from staff. There were also a number of high-profile incidents, including deaths of children due to restraints and a massive legal conspiracy to send vulnerable youth to inappropriate, often violent facilities. Despite these issues, congregate care remains a primary source of behavioral health care for system-involved youth in the U.S. In fact, increasing numbers of parents are resorting to relinquishing their children to the foster care system in a desperate effort to meet their needs. This may be due to the fact that rates of depression, suicidality, anxiety, and alienation are spiking among American youth, while many families lack access to adequate mental health care. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the number of youth experiencing mental health crises has risen rapidly, exacerbating these existing issues. The number of children who have experienced the death of a caregiver, have lived through gun violence, or are facing housing insecurity has increased too. As the youth mental health crisis rages on, this country’s weak youth support system faces a crossroads. Congregate facilities have faced steady reductions in their populations, as well as increased closures due to advocacy from survivors. In perhaps the most high profile example of this advocacy, Paris Hilton—who says she was abused as a teen in a Utah congregate care facility—has in recent years pushed to pass the Accountability for Congregate Care Act (ACCA), which would establish federal protections for youth in residential care. At the same time, child welfare and behavioral health systems have been slow to adopt a wide range of accessible, effective strategies to address youth mental health issues, especially for low-income young people. Instead, local governments continue to send kids with complicated psychosocial cases to congregate care facilities. Demi Burgess is a web developer who was sent to VisionQuest, a large youth-care agency accused of child abuse with facilities in several states. He told The Appeal he was removed from his home and sent to a VisionQuest facility in rural Pennsylvania after missing too many days of school. “I was 17, I had missed a lot of school, and all of a sudden, I’m in a courtroom, getting sentenced, I’m in a holding cell, now we’re driving five hours away,” he said. To Burgess, this mirrored how adults in his community got booked and disappeared. The judge never asked why Burgess was truant, and his mother did not have the tools to advocate for him. “Kids [at VisionQuest] were as young as 12,” Burgess said. “If we follow the logic that getting booked puts you at risk for returning to prison, this puts kids in prison early, so when they get out they aren’t scared of returning.” Municipalities must grapple with how they will reduce congregate care populations, while still addressing the massive mental health needs of our nation’s youth. In a 2021 qualitative study engaging survivors of congregate care, the research and advocacy organization Think of Us recommended that residential facilities, group homes, and other similar facilities be completely abolished due to widespread abuse within those systems. A majority of the study’s participants supported abolishing the U.S.’s current child-welfare institutions and replacing them with systems that focus more heavily on foster care, work to place children with kin as much as possible, provide more support to foster parents, and accommodate childrens’ preferences as much as possible. Some solutions are already being put to use across the country. Along with the pending ACCA legislation, 2018’s federal Family First Prevention Services Act increased funding for helpful alternatives like the recruitment of youth-friendly foster families and short-term crisis stabilization programs where youth can stabilize in short-term psychiatric stays rather than languishing in institutions for months and years. In Philadelphia, where I live, youth who have survived congregate care have successfully launched an ombudsman program meant to advocate for youth experiencing mistreatment within congregate care. Expanding the use of community-based mentors, or advocates, for low to moderate level juvenile offenders has also proven effective in multiple states in reducing long-term reliance on systems for youth support. Other promising practices include peer support for parents of youth with behavioral issues and the creation of youth community-based clubhouses. Speaking to The Appeal, Burgess recalled a cousin who was paired with a youth advocate in lieu of placement in congregate care. The pair spent quality time together instead. “He’d come home happy, talking about all the fun he just had with his advocate, and I’d think, ‘Wow, I want that.’ Maybe something like that—an adult who actually cared would have helped me with my truancy. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland called for a review last year, after the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of children who attended similar schools in Canada. An initial investigation commissioned by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland cataloged some of the brutal conditions that Native American children endured at more than 400 boarding schools that the federal government forced them to attend between 1819 and 1969. The inquiry was an initial step, Ms. Haaland said, toward addressing the “intergenerational trauma” that the policy left behind. An Interior Department report released on Wednesday highlighted the abuse of many of the children at the government-run schools, with instances of beatings, withholding of food and solitary confinement. It also identified burial sites at more than 50 of the former schools, and said that “approximately 19 federal Indian boarding schools accounted for over 500 American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian child deaths.” The number of recorded deaths is expected to grow, the report said. The report is the first step in a comprehensive review that Ms. Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary, announced in June after the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of children who attended similar schools in Canada provoked a national reckoning there. Beginning in 1869 and until the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were taken from their homes and families and placed in the boarding schools, which were operated by the government and churches. There were 20,000 children at the schools by 1900; by 1925, the number had more than tripled, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. The discovery of the unmarked graves in Canada last year — 215 in British Columbia, 750 more in Saskatchewan — led Ms. Haaland to announce that her agency would search the grounds of former schools in the United States and identify any remains. Ms. Haaland’s grandparents attended such schools. “The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies — including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old — are heartbreaking and undeniable,” Ms. Haaland said during a news conference. “It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.” The 106-page report, put together by Bryan Newland, the agency’s assistant secretary for Indian affairs, concludes that further investigation is needed to better understand the lasting effects of the boarding school system on American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians. Assimilation was only one of the system’s goals, the report said; the other was “territorial dispossession of Indigenous peoples through the forced removal and relocation of their children.” Mr. Newland said there is not a single American Indian, Alaskan Native or Native Hawaiian in the country whose life has not been affected by the schools. “Federal Indian boarding schools have had a lasting impact on Native people and communities across America,” said Mr. Newland. “That impact continues to influence the lives of countless families, from the breakup of families and tribal nations to the loss of languages and cultural practices and relatives.” The government has yet to provide a forum or opportunity for survivors or descendants of survivors of the boarding schools or their families to describe their experiences at the schools. In attempts to assimilate Native American children, the schools gave them English names, cut their hair and forbade them from speaking their languages and practicing their religions or cultural traditions. Deborah Parker, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said the children who died at government-run boarding schools deserve to be identified and their remains brought home. Ms. Parker said the efforts to find them won’t end until the United States fully accounts for the genocide committed against Native American children. “Our children had names, our children had families, our children had their own languages, our children had their own regalia, prayers and religions before Indian Boarding Schools violently took them away,” Ms. Parker said. Sitting with Ms. Haaland at the news conference was Jim Labelle, a survivor who spent 10 years in a government-run boarding school. Mr. Labelle said he was eight years old when he started there. His brother was six. “I learned everything about the European American culture,” he said. “It’s history, language, civilizations, math, science, but I didn’t know anything about who I was. As a native person, I came out not knowing who I was.” Ms. Haaland also announced plans for a yearlong, cross-country tour called The Road to Healing, during which survivors of the boarding school system could share their stories. The Canadian government has initiated similar efforts and allocated about 320 million Canadian dollars for communities affected by the boarding school system, burial site searches and commemoration for victims. Beth Wright, staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, said she hopes Congress passes two bills currently pending in the House and Senate and truly listens to any victim who may speak up. “I think the key next step is really communicating with tribal nations and survivors of Indian boarding schools to see how this support is impacting their communities,” Ms. Wright said. “We would like to see tribal communities generate their healing effort and their efforts toward truth and reconciliation.” The Department of Justice (DOJ) this week launched a website to streamline information and resources related to open missing and murdered Indigenous persons cases. The new page within the DOJ’s Tribal Justice and Safety website details the federal government’s increased efforts to address the disproportionately high rates of violence impacting Indigenous communities. The website page allows visitors to quickly report or identify a missing person; view unsolved Indian Country cases: contact the office of tribal justice; and learn more about current initiatives and upcoming listening sessions. Last year, President Biden issued a proclamation to declaring May 5, 2021 a day to “remember the Indigenous people who we have lost to murder and those who remain missing and commit to working with Tribal Nations to ensure any instance of a missing or murdered person is met with swift and effective action.” Six months later, the President signed an executive order that calls for interagency cooperation in criminal justice and public safety systems addressing missing and murdered Indigenous peoples: the act directs the Departments of Justice, Interior, Health and Human Services, and Homeland Security to work together with tribes. Simultaneously, the Department Justice launched the Steering Committee to Address the Crisis of Missing or Murdered Indigenous Persons, tasked with consultation with tribal leaders and stakeholders, with reviewing the Department’s current practices, and developing a comprehensive plan to strengthen the department’s work. That plan is slated to be submitted to the President in July 2022. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed