|

(September 24, 2021, 3:56 PM EDT) -- A California jury Thursday awarded $5 million in damages to a marijuana company that said it was prevented from opening in Richmond by a rival group of dispensaries looking to control the local cannabis market, in what the plaintiff's attorneys characterized as the first cannabis-related antitrust case.

A Contra Costa jury found that two out of three owners of Richmond Patient's Group agreed to work together to prevent Richmond Compassionate Care Collective from leasing or buying a storefront in Richmond, which caused the company harm. The jury said Darrin Parle and William Koziol had a hand in preventing Richmond Compassionate from being able to open a dispensary in Richmond, but found that Alexis Parle did not participate in the scheme. As a result, the jury awarded Richmond Compassionate $5 million in damages. Joseph M. Alioto of Alioto Law Firm, an attorney for Richmond Compassionate, told Law360 on Friday that under antitrust law the damages are trebled, and the ultimate judgment will be $15 million. Alioto said that because this is the first cannabis-related antitrust case, it's a warning that the industry is going to be governed by competition and not by monopolies. "Anytime these small businesses attempt to get into any market, opportunity is very necessary," Alioto said. "They win or they lose based on competition, and not by conspiracies to exclude them from major markets." Counsel for the defendants did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Richmond Compassionate first sued in 2016, alleging that Koziol, the Parles, their company, and some other dispensaries worked together to prevent Richmond Compassionate from opening a storefront that complied with the city of Richmond's requirements, including being 1,500 feet away from any high schools and 500 feet away from lower schools. "Such actions had the effect of restraining trade and stabilizing prices to monopolize the cannabis dispensary business in the City of Richmond," Richmond Compassionate said, noting it had suffered $15 million in damages. The conspirators presented bogus leases, letters of intent to lease or purchase, and purchase agreements to owners and landlords, all in an effort to prevent Richmond Compassionate from finding a suitable storefront that would comply with the city's code, according to the complaint. The plaintiff said the defendants' goal was to tie landlords up with a deluge of papers. The suit claimed a trust to restrain trade and form a monopoly in violation of the Cartwright Act. It sought damages, as well as a judgment of treble damages and attorney fees. The Parles and Koziol's company Richmond Patient's Group was dismissed from the suit in July, according to court records, while another company, Holistic Healing Collective Inc., was dismissed in March. Richmond Compassionate is represented by Ronald D. Foreman of Foreman & Brasso and Joseph M. Alioto of Alioto Law Firm. Darrin and Alexis Parle are represented by Scot Canell. William Koziol is represented by Barry Himmelstein of Himmelstein Law Network. The case is Richmond Compassionate Care Collective v. Richmond Patient's Group et al., case number MSC16-01426, in the Superior Court of the State of California, County of Contra Costa. By Lauren Berg

0 Comments

(September 28, 2021, 4:16 PM EDT) -- The Cherokee Nation announced Tuesday that it's reached a $75 million settlement with AmerisourceBergen Corp., Cardinal Health Inc. and McKesson Corp. over claims that the companies contributed to the opioid epidemic.

According to a statement by the Cherokee Nation, the deal will see the funds distributed over 6½ years, and it represents the largest settlement in its history. "Today's settlement will make an important contribution to addressing the opioid crisis in the Cherokee Nation Reservation; a crisis that has disproportionately and negatively affected many of our citizens," Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said in a statement Tuesday. "This settlement will enable us to increase our investments in mental health treatment facilities and other programs to help our people recover." The suit is among many by municipalities, Native American tribes and others consolidated in multidistrict litigation that claim that opioid makers and distributors as well as pharmacies are responsible for the nationwide opioid epidemic, with claims that they either misled the public about the dangers of opioids and their addictive qualities, or that they failed to take measures to prevent the illegal diversion and sale of the drugs, leaving those municipalities saddled with the costs of addressing the epidemic. Cherokee Nation Attorney General Sara Hill said the settlement will go toward helping to reduce and prevent opioid addiction and its consequences within the reservation. The settlement comes three weeks after U.S. Magistrate Judge Stephen P. Shreder paused the Cherokee Nation's bellwether trial while the parties discussed a possible global settlement of claims by the Cherokee and other tribes. While the settlement announced Tuesday only affects claims by the Cherokee Nation, according to attorneys for the tribe, the three companies said in a joint statement that the sum represents an amount consistent with what the nation would receive under a broader settlement with the other tribes in the Ohio MDL. The Cherokee Nation's suit also includes claims against major pharmacy chains; like drug distributors and manufacturers, pharmacies are facing thousands of lawsuits accusing them of contributing to a deadly plague of narcotic abuse. The settlement does not affect those claims, the Cherokee Nation said in its statement, adding it intends to "vigorously pursue" those claims through trial, which is expected to be held next fall. The Cherokee Nation is represented by its attorney general's office, Boies Schiller Flexner LLP, Fields PLLC, and Whitten Burrage. McKesson is represented by Covington & Burling LLP, and Doerner Saunders Daniel & Anderson LLP. Cardinal Health is represented by Williams & Connolly LLP, and Norman Wohlgemuth LLP. AmerisourceBergen is represented by Reed Smith LLP, and Crowe & Dunlevy. The case is Cherokee Nation v. McKesson Corp. et al., case number 6:18-cv-00056, in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Oklahoma. The MDL is In re: National Prescription Opiate Litigation, case number 1:17-md-02804, in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio. By Mike Curley --Additional reporting by Melissa Angell and Jeff Overley. Editing by Adam LoBelia. A sheriff in Georgia is protected by qualified immunity after letting an abusive deputy stay on the streets. The deputy later sexually assaulted me. The doctrine of qualified immunity has been used to protect police from civil lawsuits and trials. Here's why it was put in place. Valentine’s Day 2016 wasn’t spent celebrating love and romance. Instead, it was the day deputy Thomas Carl Pierson, of Georgia's Harris County Sheriff’s Office, grossly violated my constitutional rights. Feb. 14, 2016, was the day Pierson sexually assaulted me. I later found out that Pierson's conduct shouldn't have been a surprise, and that the Sheriff's Office and the sheriff himself – who knew Pierson was dangerous and decided to let him keep working anyway – were shielded from civil liability by the obscure legal doctrine of qualified immunity. My aggressor initially pulled me over for speeding and gave me a warning after being chatty for a few minutes.

He then asked me to pull off farther down a small road. When I didn’t, he followed me for several miles and pulled me over again using his blue lights. Pierson then turned off his dash cam and asked me to drive down a secluded road. I was terrified and did as he said. When I stopped, he pulled me from the car and sexually and physically abused me. He then warned me not to tell anyone and drove away. Pierson convicted of sexual assault Unlike most sexual assault victims who fear not being believed or have other reasons for not speaking up, I immediately reported the incident. In August 2017, Pierson was found guilty of sexual assault on a person in custody and six other charges related to traffic stops with myself and two other women. Two months later, he was sentenced by a Georgia Superior Court judge. In the course of the lengthy legal process, I found out that six months before his assault on me, on Aug. 31, 2015, Pierson was involved in an excessive force incident that killed Nicholas Dyksma. Pierson's boss, Sheriff Robert Michael Jolley, knew about the officer's involvement in Dyksma's death. Jolley let Pierson continue to patrol the streets of Harris County, anyway. In July 2018, the same 11th Circuit Court judge who would later rule on my case, heard the case on behalf of Nicholas Dyksma's family. Judge Clay Land ruled that Pierson wasn't protected under qualified immunity in the Dyksma case, but that the sheriff and his office were. That case was settled on appeal. Kimberly Beck: My son was killed by a park ranger. Qualified immunity means I may never see justice. I sued Pierson, Harris County and Sheriff Jolley for violations of my Fourth and 14th Amendment rights and civil rights violations based on Jolley's policies and customs of tolerating abusive cops on the force. I have suffered from a litany of physical and mental health issues since the brutal assault by a police officer. But because of qualified immunity laws, I am left without any substantive legal recourse, and Jolley remains in office. Qualified immunity left me with no recourse The judge-made doctrine of qualified immunity was created during the 1960s civil rights era and was later expanded in the 1980s. Its intentions appear noble at first – the idea was to provide police officers and other government officials with protection from lawsuits so long as their conduct didn't violate "clearly established law or constitutional rights of which a reasonable officer would have known." In practice, however, the second part of the doctrine, which asks whether a constitutional right that was violated was "clearly established," has come to mean that as long as there is not a factually identical case in the same jurisdiction, police officers, their superiors, and other abusive and negligent government workers cannot be held civilly liable for violations of the Constitution. Qualified Immunity: My brother wanted to go to the bathroom. Police killed him instead. Until the U.S. Supreme Court steps in, judges can't seem to make up their minds about the doctrine, and we end up with absurd case law as a result. Judge Clay Land ruled that Jolley and his office were protected by the doctrine of qualified immunity in my case because they weren't on notice that an abusive cop might engage in a different kind of violence – that of sexual assault. The judge decided that Jolley was off the hook because the facts weren't the same in the two cases The injustice does not end there. Even though Pierson was held criminally liable in my case, because his conduct was found to be intentional, the Sheriff's Office claims he is not covered under Harris County's insurance policy. Since he is jailed and doesn't have an income, he is essentially judgment proof. While I find comfort in knowing that my aggressor is behind bars, seeing Jolley and the Harris County Sheriff's Department escape civil liability is a miscarriage of justice that I have to deal with every single day for the rest of my life. That is why I advocate for reform of qualified immunity laws. In March, the U.S. House passed the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. It would lower the criminal intent standard from “willfully” and inserting “knowingly or recklessly” to convict a law enforcement officer for misconduct in a federal prosecution. It also would limit qualified immunity as a defense to liability in a civil action against a police officer and grant subpoena power to the Department of Justice Qualified immunity keeps bad cops on the streets, prevents victims from recovering for damages and shields police departments from their legal obligations. Harris County and Sheriff Jolley gave Thomas Pierson access to his badge and sent him out to “work.” They should be held accountable. Lynette Christmas, a mother of three and grandmother of five, is a sexual assault survivor and local advocate for justice. This column is part of a series by the USA TODAY Opinion team examining the issue of qualified immunity. The project is made possible in part by a grant from Stand Together. Stand Together does not provide editorial input. Two weeks after the 6o-foot-tall statue of Robert E. Lee was removed in Richmond, Va., the former Confederate capital city has become home to a new statue, this one commemorating the abolition of slavery. The Emancipation and Freedom Monument — designed by Thomas Jay Warren, a sculptor based in Oregon — was unveiled Wednesday on Brown's Island on the James River in downtown Richmond, about 2 miles from where the Lee statue once stood. It consists of two 12-foot bronze statues of a man and a woman holding an infant who have been newly freed from slavery. The statue's pedestal includes the names, images and stories of 10 Virginians who contributed to the struggle for freedom before and after emancipation, including Dred Scott, whose lawsuit led to the Supreme Court decision that persons of African descent were not U.S. citizens; Nat Turner, who led a successful slave rebellion; and educator Lucy Simms. "It really captured what we were trying to do in that the figures capture the emotion of emancipation, but the people on the base capture who else was involved of the process of fighting against slavery, leading to emancipation, and fighting for freedom and equality going forward," state Sen. Jennifer McClellan told NPR.

McClellan, who is head of the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Commission, which took the lead on commissioning the statue, has been working to build the monument since 2011. The monument was originally supposed to be revealed in 2019 as part of the 400th anniversary of 1619, when the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia. But the fact that the monument will now make its debut after some of the largest Confederate statues in Richmond of Lee and other generals are gone is a moment of "poetic justice," McClellan says. "This monument has always represented an important part of healing," McClellan said. "Having that happen after COVID, after the George Floyd murder and the reckoning with racial inequity and after the monuments started coming down, it's much more healing than it would have been in 2019." by Deepa Shivaram By Sam Reisman

(September 8, 2021, 6:35 PM EDT) -- California's newly centralized Department of Cannabis Control on Wednesday published its proposed regulations governing how all legal commercial marijuana activity in the Golden State will be overseen. The publication of the emergency regulations — approximately 400 pages of revisions and deletions — comes some two months after the state unified its regulation of all aspects of its cannabis market, including cultivation, manufacture and sale, under the DCC's purview. "Today's action reflects the governor's commitment and our ongoing effort to streamline requirements for California cannabis businesses and simplify participation in the legal, regulated market," said Nicole Elliott, director of the DCC, in a statement. "Many of the proposed changes are the direct result of feedback received during consolidation." The DCC consolidated functions that were previously performed by three entities: the Department of Consumer Affairs' Bureau of Cannabis Control, the Department of Food and Agriculture's CalCannabis Cultivation Licensing Division, and the Department of Public Health's Manufactured Cannabis Safety Branch. The agency said the new emergency regulations are meant to codify and harmonize the once distinct regulatory schemes, particularly over license application criteria and who can hold equity interest in a cannabis business. Griffen Thorne, a cannabis attorney at Harris Bricken LLP, told Law360 that the legacy rules governing ownership of cannabis licensees from the BCC, which oversaw retailers, seem to have in large part been applied to cultivators and manufacturers. "I think life is going to be a little more difficult for manufacturers and cultivators in general," he said, referring to the need to disclose ownership to regulators. "People are going to have to go back and reevaluate, just to make sure they've done things in a kosher way." The rules also address how to properly handle trade samples within the cannabis industry. Overseeing trade samples is a responsibility specifically delegated to the DCC by A.B. 141, the legislation that created the agency that was signed into law in July. "Trade samples had been the bane of everyone's existence in the industry," Thorne said. "In any industry you need to sample goods. We knew that was going to come down." The release of the regulations kicks off a five-day public notice after which the rules will be filed with the state's Office of Administrative Law. The DCC will accept comments on the regulations until Sept. 21. -Additional reporting by Hailey Konnath. Editing by Adam LoBelia. Documentary in the Works Oglala Sioux Jesse Short Bull is directing the film by Mia Galuppo

Lakota Nation vs. the United States, a feature-length documentary chronicling the Lakota Indians’ quest to reclaim the Black Hills, is in the works from non-fiction studio XTR with Mark Ruffalo attached as an executive producer. The film is currently in production, with Oglala Sioux Jesse Short Bull directing, with MLK/FBI editor Laura Tomaselli. The doc features the work of Nick Tilsen and Krystal Two Bulls, activists and founders of the #landback movement in South Dakota. “Lakota Nation vs. the United States isn’t an isolated event in history books — we’re all still paying for it. Our work through this film confronts episodes of our history that have conveniently been chosen to be forgotten, in order to lead to solutions and cease such deplorable atrocities from happening against generations to come,” said Jesse Short Bull. Benjamin Hedin is producing, with Ruffalo and Sarah Eagle Heart executive producing, along with Kathryn Everett and Bryn Mooser from XTR. “Our hope is that this stirring meditation on the nature of justice highlights the much-needed atonement for the misdeeds of history and what can be done in the present day to begin repairing the wrongs of the past,” said Everett, head of film at XTR. Said Eagle Heart, “Our work through this film confronts episodes of our history that have conveniently been chosen to be forgotten, in order to lead to solutions and cease such deplorable atrocities from happening against generations to come.” Added Ruffalo: “The fight for Black Hills is far from over and our intention is to support the Lakota people by raising awareness for the injustices they face in present-day America. The perception in many Americans’ minds is this is only historical, this ‘happened.’ What they don’t understand is that it is happening now. It is today, it is immediate and mostly hidden from your eye. This is a current issue.” By Khorri Atkinson

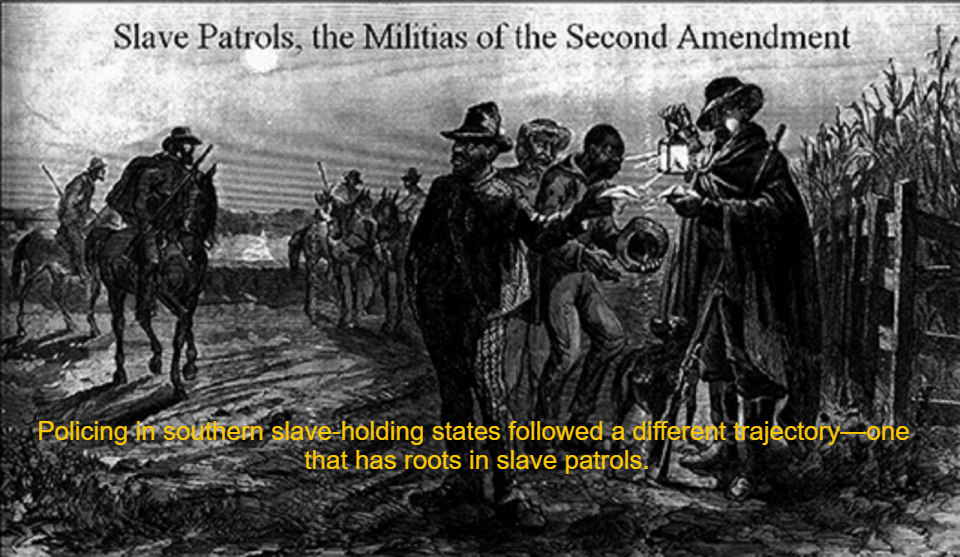

(September 21, 2021, 5:27 PM EDT) -- The U.S. Senate voted along largely partisan lines Tuesday to confirm President Joe Biden's selection of a civil rights and criminal defense attorney for a long-vacant lifetime judgeship at the District of New Mexico. Margaret Strickland, who formerly worked at the New Mexico Law Offices of the Public Defender, won confirmation by a vote of 52-45 that saw Republican Sens. Susan Collins of Maine, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska joining all Democrats present in support. Strickland was on Biden's first slate of 11 judicial nominees announced in March, and her confirmation comes as the White House is making an unprecedented push for race, gender and professional diversity on the federal bench across the country. She's also one of a growing number of criminal defense lawyers Biden is naming to the federal judiciary's ranks amid objections from Republicans who complain about their weak civil litigation expertise. During a May confirmation hearing, Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the top Republican on the Judiciary Committee, said "there's nothing wrong with being a criminal-defense attorney" as they provide legal service to "protect their clients' constitutional rights." But he rebuked liberal groups like Demand Justice he argued "have made it clear that's not what they want. They seem to think that these criminal-defense judges will defund the police from the bench." The advocacy organization, founded by two veterans of the Obama administration, has been pushing the Biden White House to look beyond BigLaw for judicial candidates and not to select former prosecutors or corporate attorneys who they say too often align with conservative interests. Strickland told Grassley at the May hearing that she had spoken two or three times with Demand Justice leader Christopher Kang. The nominee also insisted that she knows the difference between an advocate's role and that of a judge, who must "approach every case neutrally, deliberately putting aside any personal opinions in order to fairly consider the facts, the law and any arguments from counsel." Strickland had started McGraw & Strickland LLC in 2011 after her five-year stint as a state public defender. Her firm biography calls her "Your Voice Against Police Brutality" and noted that she won a $1.6 million jury verdict in a civil rights case against Las Cruces, New Mexico, police officers. At her confirmation hearing, Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., took Strickland to task over her views on qualified immunity, the 50-year-old U.S. Supreme Court doctrine that limits private civil rights suits against government officials including police officers. Kennedy said she had "spent [her] entire adult career arguing against qualified immunity." Strickland told the lawmaker she would not apply her personal views while on the bench, but Kennedy insisted she would. "You're going to do everything you can to undermine qualified immunity, aren't you?" he asked. "No, senator, qualified immunity is the law of the land … and I would apply it," the nominee replied. "I do believe, senator, in qualified immunity. It is the law of this country." Ahead of Tuesday's vote, Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., said on the floor that Strickland "is a highly qualified nominee with the right experience, temperament and disposition to be a fair-minded district court judge." "She has spent her entire professional career working in the community in which she will sit," the senator added. "She knows intimately the impact the legal system has on everyday Americans and she understands that serving as a judge is very different from serving as an advocate." The Las Cruces-based judgeship Biden selected Strickland for has been vacant since July 2018 when U.S. District Judge Robert Brack, a George W. Bush appointee, assumed senior status. This was also one of the 26 vacancies then-President Donald Trump lost his shot to fill in January after lawmakers voted to certify Biden's presidential victory and then went on recess. Trump had selected Fred J. Federici, a Venable LLP alum and a top federal prosecutor in the state, for the post. Strickland earned degrees from the University of Texas at El Paso and New York University School of Law. She started her career at the Las Cruces Office of the New Mexico Public Defender and then started her own firm, representing indigent defendants in federal court. by Connie Hassett-Walker Before the summer of 2020 #BlackLivesMatter demonstrations nationwide following the death in May of George Floyd from a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on his neck; before the 2015 Baltimore, Maryland, protests after the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody; and before the Ferguson, Missouri, protests after the 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown by a police officer (and the lack of indictment of the officer who shot Brown); there were the Los Angeles riots of 1992 after the acquittal of police officers for beating up Rodney King. Before the 1992 Los Angeles riots came the 1965 Watts Riots (also in Los Angeles) after an African American driver and his stepbrother were pulled over by the police. The Watts Riots occurred in August 1965, days after the Voting Rights Act was signed, months after the Selma-to-Montgomery Civil Rights march occurred, and a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Civil Rights Act banned segregation in public spaces, as well as employment discrimination based on race, gender, national origin, or religion. Building on this, the Voting Rights Act targeted legal barriers that states and municipalities had erected (e.g., poll taxes, literacy tests) to prevent African American men from voting in the wake of the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870. Perhaps it was the possibility that ending discrimination against African Americans might be possible that caused frustration that was previously tamped down to finally became unbearable. Centuries of suppressed anger—over systemic racism, housing discrimination, Black/white income disparities, poverty, police harassment—finally boiled over in 1965 in Watts, a Black neighborhood in Los Angeles. African Americans took to the street to say, “enough is enough.” Yet, tenuous police/Black community relations arguably haven’t improved that much during the past 50 years. The protests, and mistrust, continue to this day (see, for example, the 2016 documentary Stay Woke: The Black Lives Matter Movement). How did we get here? There are two narratives of how U.S. policing developed. Both are true. The more commonly known history—the one most college students will hear about in an Introduction to Criminal Justice course—is that American policing can trace its roots back to English policing. It’s true that centralized municipal police departments in America began to form in the early nineteenth century (Potter, 2013), beginning in Boston and subsequently established in New York City; Albany, New York; Chicago; Philadelphia; Newark, New Jersey; and Baltimore. As written by Professor Gary Potter (2013) of Eastern Kentucky University, by the late nineteenth century, all major American cities had a police force. This is the history that doesn’t make us feel bad.

While this narrative is correct, it only tells part of the story (Turner et al., 2006). Policing in southern slave-holding states followed a different trajectory—one that has roots in slave patrols of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and police enforcement of Jim Crow laws in the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. As per Professor Michael Robinson (2017) of the University of Georgia, the first deaths in America of Black men at the hands of law enforcement “can be traced back as early as 1619 when the first slave ship, a Dutch Man-of-War vessel landed in Point Comfort, Virginia.” When a relationship begins like this, can citizen mistrust of police ever fully be overcome? Has policing as an institution evolved far enough away from its origins to warrant Black communities’ trust? This article isn’t the first public discussion of the history of racism in policing. Indeed, racism in policing is officially acknowledged by the National Law Enforcement Museum. More famously, comedian Dave Chappelle did a bit about it at the Brooklyn club, the Knitting Factory, back in 2015. A piece about the issue, published by the author in 2019 in the scholarly magazine The Conversation, got a lot of traction after the death of George Floyd. As of this writing, over 240,000 people have read that article. The reactions to The Conversation article have varied from positive to negative. Some readers agreed or wrote that it confirmed what they already suspected. Others disagreed (“It’s [police/citizen relations] not much better for white people”) or tried to minimize feelings of guilt (“black Americans played a significant role in the slave trade! So there is lots of blame to go around”). A few annoyed readers took the time to send an email rather than simply posting a comment in the comment section. One email received simply said, “Your a moron.” (The author resisted the urge to reply that if the emailer wished to call the author a moron, then the emailer should use proper grammar.) Why should there be hostility to simply reminding people of the history of events that already happened? After all, we—Americans—did this. Isn’t owning one’s actions the right thing to do, even if it makes us feel bad for a while? The ugly past should be revisited because there is still a problem with police/community relations with respect to African Americans. How You Start: Slave Codes and Slave Patrols Originating in Virginia and Maryland, the American slave codes defined slaves from Africa as property rather than as people (Robinson 2017); that is, without rights. American slave codes were rooted in the slave codes of Barbados. According to Dr. Robinson (2017), the British established the Barbadian Slave Codes (laws) “to justify the practice of slavery and legalize the planters’ inhumane treatment of their enslaved Africans.” American policing in the South would begin as an institution—slave patrols—responsible for enforcing those laws (Turner et al., 2006), as slave uprisings were a threat to the social order and a chronic fear of plantation owners. The first slave patrols were founded in the southern United States, the Carolina colony specifically (Reichel, 1992), in the early 1700s. By the end of the century, every slave state had slave patrols. According to Dr. Potter (2013), slave patrols accomplished several goals: apprehending escaped slaves and returning them to their owners; unleashing terror to deter potential slave revolts; and disciplining slaves outside of the law for breaking plantation rules. Described by Turner et al. (2006), slave patrols were a “government-sponsored force [of about 10 people] that was well organized and paid to patrol specific areas to prevent crimes and insurrection by slaves against the white community” in the antebellum South. Without warrant or permission, slave patrols could enter the home of anyone—Black or white—suspected of sheltering escaped slaves. (In modern times, this would be a clear violation of the Fourth Amendment and constitute an illegal search.) After the Civil War ended, the slave patrols developed into southern police departments. Part of the early police’s post–Civil War duties was to monitor the behavior of newly freed slaves, many of whom, if not given their own land, ended up working on plantations owned by whites and to enforce segregation policies as per the era’s new Black Codes and Jim Crow laws. The first Black Codes were passed in 1865, shortly after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery. The codes were laws that specified how, when, and where freed slaves could work and how much they would be paid. Essentially, the Black Codes maintained the de facto structure of slavery without formally calling it “slavery.” Other Black Codes restricted Blacks’ right to vote, dictated how and where they could travel, and where they could live. Because many ex-Confederate soldiers had transitioned to working in policing or elsewhere in the justice system (e.g., as judges), the justice system, including law enforcement, perpetuated the oppression of African Americans. In the 1880s, new forms of Black Codes known as Jim Crow laws were enacted across southern states. In effect until 1965, these new laws prohibited Blacks and whites from sharing public spaces, such as schools, libraries, bathrooms, and restaurants. The hardships of life for African Americans in the Jim Crow South (Mississippi, specifically) are the focus of a recent book by Jim Sturkey, Hattiesburg: An American City in Black and White. Perhaps the most infamous image from this era is the separate but “equal” water fountain for white versus colored individuals, taken in 1950 by Elliot Erwitt in North Carolina (see here). Blacks who broke the law or violated norms during the Jim Crow period were often met with brutality at the hands of the police (Robinson, 2017). Fast forward to the 1960s and the formal end of the Jim Crow era. The Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act came during a decade of much social and political upheaval. Opposition to the Vietnam War and other protest movements—for civil rights, women’s rights, victims’ rights, prisoners’ rights—signaled that America had entered a new era of challenges to the status quo. In July 1964, civil rights activist Malcolm X would denounce what he called New York police’s “outright scare tactics” in responding to racial tensions in the city. During this time of upheaval, the police acted as enforcers of the status quo. It was no longer about quashing slave uprisings. Indeed, citizen protests and police response to those protests were not just happening in the former slave states but throughout the country. According to Dr. Victor Kappeler (2014) of Eastern Kentucky University, the police were now tasked with responding to anyone who pushed back against the existing social, political, and economic structure of America—which seemed to disadvantage the poor and people of color. During the summers of the late 1960s, race riots broke out in cities across the country, particularly in 1967 and after the 1968 assassination of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The police responded at times harshly to the riots using dogs, fire hoses, and tear gas. As an aside, it is worth mentioning that policing isn’t alone in the criminal justice system in having an issue with institutional racism and discrimination. Other parts of the system—including courts and corrections—are also affected. Two words: wrongful conviction. Ava DuVernay’s excellent Netflix miniseries When They See Us portrays the heartbreaking ordeal of the men—Korey Wise, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Antron McCray, and Yusef Salaam—known as the Central Park Five. Decades earlier came the wrongful conviction of teenagers known as the Scottsboro Boys. They were also falsely accused of raping two white women. These are not isolated incidents. How We Finish? For the record, the point of this article is not to assert that individual police officers are racist. The author has friends, family, and students in law enforcement who are good, ethical people and who view their primary job as to protect and serve the public. When speaking with police officer friends and family members in the wake of George Floyd’s death, the word that came up most often was “disgusting” (how Floyd died). The point is that the overall institution had a terrible start in some (not all) aspects, for which there has never been a reckoning. Perhaps if policing—and the justice system more broadly—had done a better job of reconciling with its racist past, there wouldn’t be calls currently to defund the police. There have been some improvements. There is greater awareness of the need to have a more diverse police force. There is also more understanding among police of the importance of handling citizens with care; and that brutality—particularly lethal force—against citizens can lead to citizen mistrust of police and community outrage. There are calls for police to wear body cameras to monitor police behavior so as to reduce police abuse of their power by increasing transparency of police behavior. (Studies [e.g., Hedberg et al., 2017] on the effectiveness of body-worn cameras show mixed results. See, for example.) Groups like Blacks in Law Enforcement of America and 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care (“100 Blacks”) now exist and have a voice as well as a social media presence. Police departments nationwide are more diverse, including the hiring of more Blacks, Hispanics, and women, although there is room for improvement. In the past 10 years, the rise of technology, like smartphones, and social media platforms, like YouTube and Facebook, have empowered citizens to capture real-time video of police encounters. The author is cautiously optimistic that the institution of policing is evolving away from the racially oppressive part of its roots. Yet, issues remain, such as racial profiling (Meehan & Ponder, 2002). In New York City, police stop-and-frisk practices have been the subject of a recent federal lawsuit that found them to be unconstitutional in that they unfairly target Blacks and Hispanics. A new study by Stanford University researchers of 100 million traffic stops nationwide found evidence of racial profiling by officers in stopping drivers (Pierson et al., 2020). The researchers found that Black and Hispanic drivers were stopped and searched more frequently than were white drivers, but this drops after sunset when the driver’s race is harder to spot from a police car. How far we have come, how far we have yet to go. (September 9, 2021, 10:40 PM EDT) -- Cannabis policy experts warned on Thursday that federal legalization could trigger a regulatory crisis for an industry that's been governed by state law for close to a decade, potentially rolling back social equity programs and eroding years of regulations.

The ramifications of creating an interstate cannabis market overnight would be felt most acutely by smaller businesses unable to compete with multistate giants, and by state regulators suddenly forced to adapt their policies in ways that would likely limit their power. The comments were aired at a webinar moderated by Andrew Kline, senior counsel at Perkins Coie LLP, and echo many in the industry who have urged federal lawmakers to slowly roll out legalization so as not to radically alter state cannabis markets. "It's always the smallest businesses and most marginalized groups that suffer the most when you introduce this kind of chaos," said panelist Shaleen Title, a former regulator with the Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission and CEO of the social equity-focused think tank Parabola Center. According to panelist Robert Mikos, a professor at the Vanderbilt Law School who has studied the intersection of federalism and cannabis policy, many states enacted their regimes under the assumption that the federal prohibition on cannabis effectively turned off the dormant commerce clause: a constitutional doctrine that limits states' power over interstate commerce. Federal legalization, as envisioned by the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, or CAO Act — released in draft form in July by Senate Democrats — would "remove any doubts that this normal background principle of constitutional law applies to the cannabis market," Mikos said. "And because of that principle, you're going to see challenges to all sorts of state regulations." For example, many states put in place residency criteria requiring that cannabis licensees have in-state residency on the grounds that it makes the industry easier to oversee or because voters expected legalization to benefit their fellow residents. These requirements have been frequently challenged in court on constitutional grounds, with uneven results, but panelists warned that federal legalization without explicit congressional legislation suspending the dormant commerce clause could be their undoing. Some states implemented their social equity policies by privileging applicants that hail from certain zip codes disproportionately harmed by prohibition, and these rules too could be struck down as de facto residency requirements, the panelists said. While some of these policies may have been designed with protectionist intentions, many were developed as practical matters to help regulators track marijuana to guard against diversion to minors, non-patients and out-of-state sellers, Mikos said. "They developed these track-and-trace systems, and those are only feasible as long as you restrict interstate commerce in cannabis," he said. "They created these closed-loop systems within a state. ... Those sorts of things don't work very well when you bring in product from outside the loop." The panelists also warned of a potential "race to the bottom," with more onerous regulations being struck down in favor of more relaxed ones as policymakers angle to make their state more welcoming to cannabis businesses that can freely move to another state. The panelists were generally supportive of the CAO Act — co-authored by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and Sens. Cory Booker, D-N.J. and Ron Wyden, D-Ore. — and they applauded its criminal justice reform and cannabis descheduling components. Kline, former director of public policy for the National Cannabis Industry Association, said that despite the draft bill's silence on the dormant Commerce Clause and the industry's concerns about an interstate market, stakeholders agreed that descheduling cannabis should have happened "yesterday." But the bill's relative lack of substance in preserving state autonomy is still a pressing concern. According to panelist Jeremy Unruh, a public and regulatory affairs executive at multistate cannabis company PharmaCann LLC, the provision of the CAO Act that outlines states' rights to regulate cannabis may be more toothless than it seems, since it borrows language from preprohibition laws governing how states can regulate alcohol. Decades of Supreme Court decisions have interpreted those laws under the 21st Amendment, which ended alcohol prohibition, with the upshot that states have less power. "They've eroded that language that's in the CAO Act so it doesn't give the states much more discretion to regulate cannabis coming in from other states than any other commodity," Unruh said. "There really aren't any special protections states can use to ensure the stability of their state programs," he added. By Sam Reisman |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed