|

The Doe Fund says it pays homeless and formerly incarcerated people New York City’s minimum wage of $15 per hour. But the nonprofit charges weekly fees that can drive their wages below the federal minimum of $7.25. Jonathan Ben-Menachem

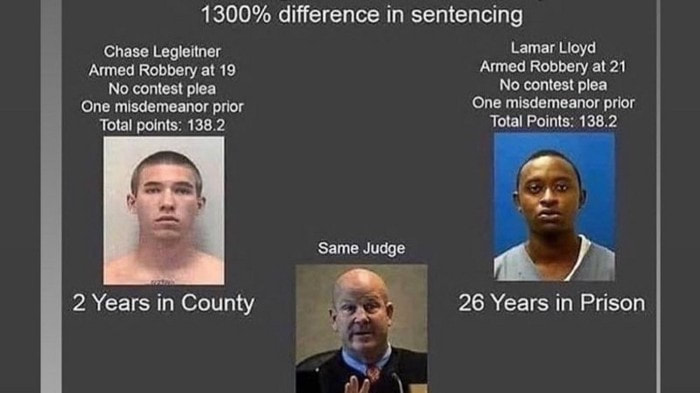

Jul 29, 2020 Blue-shirted men wielding brooms are a common sight in New York City’s business improvement districts (BIDs) where the city entices real estate development and an influx of new business investment. The workers are some of the city’s most vulnerable people—the formerly incarcerated, homeless or sometimes both—and they are paid and managed by the Doe Fund, a nonprofit at the nexus of welfare and the criminal legal system. But the Doe Fund is not their employer. Instead, the nonprofit’s lowest-paid laborers are legally considered “clients” in a workforce development program, so they don’t have the typical protections that New York City workers enjoy. According to contract language reviewed by The Appeal, Doe Fund client pay is not considered a wage, but instead a “training incentive” that recognizes “progress in the program.” The Doe Fund says it pays clients New York City’s minimum wage of $15 an hour, but its workers receive far less. Until this month, the Doe Fund charged a $165 weekly fee to all clients. On July 1, the fee increased to $249 each week. Because it’s a flat fee removed from clients’ weekly paychecks, the fee now drives $15 per hour pay well below $8 an hour—and in some cases, even lower than the federal minimum wage of $7.25. According to the Doe Fund, clients typically work 35 hours each week. A person working 35 hours—30 paid hours, excluding lunch breaks—would earn just $201 after the Doe Fund charges its $249 fee, or $6.70 an hour. In a telephone interview with The Appeal, Bill Cunningham, a Doe Fund spokesperson, noted that the wages from the program aren’t taxed. But a New York City worker making minimum wage earns about $12 per hour after tax, significantly higher than the sum earned by Doe Fund clients. There’s legal precedent supporting the notion that this “workfare” arrangement violates minimum wage laws. In 1995, 40 homeless plaintiffs sued the Grand Central Partnership claiming that they were paid below minimum wage. That BID was paying people $1 to $1.50 an hour, a small fraction of the city’s $4.25 minimum wage; the Doe Fund is paying its clients a slightly larger fraction of minimum wage. “We are alarmed to learn of complaints that the Doe Fund is deducting $100 more per month from the pay of homeless workers, possibly resulting in sub-minimum wages,” said Shelly Nortz, deputy executive director for policy with the Coalition for the Homeless (which represented homeless plaintiffs in that class action suit). In 1998, U.S. District Judge Sonia Sotomayor—now a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court--ruled that the Grand Central Partnership BID violated minimum wage laws. “Despite the defendants’ intent, they did not structure a training program as that concept is understood in case law and regulatory interpretations but instead structured a program that required the plaintiffs to do work that had a direct economic benefit for the defendants,” Sotomayor wrote. “Therefore, the plaintiffs were employees, not trainees, and should have been paid minimum wages for their work.” Critics characterize BIDs as “shadow governments” that rake in millions while paying comparatively little for performing services like cleaning city streets. A 2016 article by Crain’s New York found that clearing litter from sidewalks and gutters accounts for just 25 percent of the $130 million spent by BIDS every year. The Doe Fund’s workforce development program, then, supports the efforts of New York City commercial landlords and business owners to avoid paying for comparatively more expensive sanitation workers. Contracts with unionized workers would cost businesses about three times as much. “It’s feudalism, pure exploitation,” one Doe Fund program client told The Appeal under the condition of anonymity. “They receive money from the city and private donors, and they take money from us. A thousand dollars a month. Where is it going?” The answer to that question remains unclear. Cunningham said the fee was increased for several reasons, the foremost being that BIDs haven’t changed their $12 per hour contracts with the Doe Fund to reflect minimum wage laws. He also pointed to unexpected coronavirus-related costs, such as PPE and transporting meals to hotels leased by the city. And he told The Appeal that the fee funds services for clients—housing, food, clothing, vocational training—and repeatedly compared the program fee to the cost of rent for individuals earning minimum wage while insisting that the Doe Fund was more favorable for clients, even when clients earned below the federal minimum wage. Earlier this year, New York State Assembly member Andrew Hevesi introduced a bill that would prevent homeless shelters from charging rent to residents, and its provisions may apply to the fee that the Doe Fund charges its clients. “People should not be forced to hand over their hard-earned income from low-wage work cleaning city streets to the operator of their shelter,” Nortz of the Coalition for the Homeless told The Appeal in an email. Doe Fund executives George and Harriet McDonald each pay themselves about $430,000 per year, and their son, John McDonald, earns a $290,000 yearly salary as executive vice president of real estate. The Doe Fund’s headquarters is the McDonald family brownstone on the Upper East Side, and the nonprofit pays for that, too, at a yearly cost of $200,000 on “rent and utilities.” Blue-shirted Doe Fund clients clean the McDonalds’ street as part of their “beautification” route, powerfully illustrating the family’s use of formerly incarcerated labor for personal benefit. The Doe Fund is also contracted by the New York City Department of Homeless Services to operate shelters across the city, including facilities in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Bushwick. Over 600 people live in the Doe Fund’s shelters and hotel rooms leased by the city, and 410 of those people participate in the nonprofit’s workforce development programming. The Doe Fund’s shelters don’t just serve homeless people—they also house many formerly incarcerated men. One of the organization’s stated goals is to reduce recidivism and help people successfully re-enter society. About half of the workforce development program’s 410 clients are on parole or community supervision, and roughly 75 percent have had some experience with the criminal legal system. The workforce development program contract specifies that noncompliance with its conditions can result in a parole violation. Former Doe Fund employees say that many of the conditions are racist and paternalistic: Contract language prohibits “visible underwear” and “do-rags,” imposes a 10 p.m. curfew, bans pornography, and requires that clients submit to “random drug and alcohol testing” and fingerprinting. The contract also notes that parole officers will be consulted if shelter residents request a curfew extension to, for example, spend a weekend with a family member off site. In the first month of the Doe Fund’s programming, clients clean and maintain the shelter buildings; once “orientation” is complete, clients begin “beautifying” public and private spaces in the city as part of the workforce development phase. Because sanitation work is legally considered part of the workforce development program and not employment, clients have to work in order to remain in the program and receive vocational training. Clients only “graduate” after completing vocational training classes over the course of nine to 12 months. But these courses disappeared during the coronavirus pandemic, which leaves clients in a state of limbo where they’re expected to work indefinitely while earning below minimum wage. Clients have not been provided a date for when the bulk of vocational training will resume. In an email statement, the Doe Fund said it had resumed some educational and vocational courses with a mixture of in-person and remote learning starting July 3—but clients told The Appeal that they hadn’t been in class since early spring. Researchers say the Doe Fund should be situated not just in business improvement but in the broader political economy of prisoner re-entry. Reuben Jonathan Miller, assistant professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration, told The Appeal that the precarity of Doe Fund clients symbolizes a concept he calls “carceral citizenship,” an alternate form of political membership for people who have been accused or convicted of a crime. “Criminality is doing this interesting work of translation,” he said. “You’ve got 40 hours of work, but I’m going to take $250 each week. The criminal label lets you do that. If this happened with anybody else, you might call it exploitative—but because it’s formerly incarcerated people, not so much. Where are you going to go for a new job? Who are you going to complain to?” Indeed, formerly incarcerated people typically experience much higher unemployment rates than the general population—especially in pandemic era New York City where the unemployment rate is above 20 percent. The Doe Fund’s website proudly notes that clients were deemed “essential workers”—though they don’t have legal status as employees—and deployed to clean streets throughout the darkest stages of the pandemic in the spring. Miller also emphasized that re-entry service providers typically focus on individual transformation—“soft skills” such as changing one’s attitude toward work—instead of direct connections to the labor market and permanent housing. He says the Doe Fund’s use of the term “graduate” is both intentional and meaningful. “Graduates are credible messengers,” Miller said. “They are people who have changed their lives. I was blind, now I see. Now I run a program. This is a redemptive story. But ritual and symbolism aren’t enough.” The Doe Fund’s sanitation services are primarily funded by BIDs, which are part of New York City’s gentrification engine—and policing is deeply connected to gentrification. The city’s first BID was formed in 1984, and the districts function as a sort of public-private extension of city government that have been called “cartels for landlords.” Broadly speaking, BIDs are a symptom of white flight and the reduced tax base that accompanies it; businesses that depended on tax-funded city services (including sanitation) turned to BIDs in order to keep costs low. BIDs played a significant role in former Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s “clean up” of Times Square in the mid-1990s, where adult establishments and sex workers were ruthlessly targeted by city officials. In 1998, the city implemented a zoning law that banned a variety of adult businesses from operating within 500 feet of schools, homes, and churches. The Times Square Alliance BID acted as a sort of anti-pornographic custodian in the 2000s, taking steps to push out businesses that attempted to circumvent loopholes in that zoning law. Although the Doe Fund contracts with several BIDs, including Dumbo and Downtown Brooklyn, not all BIDs use nonprofit intermediaries to reduce wages and deny legal protections to their workers. For instance, the Downtown Alliance BID employs at least some unionized sanitation workers, as does the 34th Street BID. BIDs have close working relationships with the NYPD, and often hire their own security forces to extend “order maintenance” policing more fully. In San Francisco, police used BID surveillance cameras to spy on protests against police violence in real time. So, if police and private security forces can be considered the “front end” of gentrification—ushering “disorderly” people away from sites of real estate and commercial development with tickets and arrests—coercing underpaid formerly incarcerated laborers to “beautify” sites of gentrification might be considered the “back end.” The Doe Fund’s influence extends deep into New York politics. The nonprofit is a real estate developer, and the organization maintains more than 1 million square feet of housing in part through financial support from New York State. In addition to receiving tens of millions of dollars in public funds to operate homeless shelters, the organization lobbies the city on homeless services policy (and situates its own services as a better “solution” to homelessness than permanent housing). This political work also crops up in the personal politics of Doe Fund management; last year, Politico reported that employees who criticized the Amazon HQ2 deal (or Governor Andrew Cuomo more generally) faced retaliation from George McDonald. The McDonald family has donated at least $250,000 to Cuomo’s election campaigns. The Doe Fund is also tied to New York City’s political leadership: former Mayor Michael Bloomberg has given the organization millions of dollars, and the Doe Fund reciprocated this support by sending “van loads” of program clients to testify in favor of his third term in 2008. Connections like these aren’t lost on the Doe Fund’s clients. “George McDonald and Michael Bloomberg are best friends. They were shooting pool in one of the facilities together,” one client told The Appeal. The Doe Fund appears poised to export its welfare-punishment framework nationwide: The organization’s most recent annual report notes that its model is expanding into other cities, including Atlanta, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and two cities in Colorado. But it’s possible that cities where George McDonald holds less political sway could resist the expansions.

4 Comments

Fighting for native rights: Ever resilient, Boulder-based Native American Rights Fund turns 507/29/2020 John Echohawk, executive director and founding member of the Native American Rights Fund, has worked in law for half a century protecting the rights of native people and tribes in court. Now 74 years old, he plans to work as long as he is in good health

NARF, a nonprofit legal firm specializing in federal Indian law, was established 50 years ago. This area of law refers to “a complex body of law composed of hundreds of Indian treaties and court decisions, and thousands of federal Indian statutes, regulations and administrative rulings,” according to NARF’s website. The organization concentrates on existing laws and treaties and takes on cases where those rights are threatened. NARF’s main office is in Boulder, with two others in Anchorage, Alaska, and Washington. Since its founding, NARF has represented plaintiffs in major cases. Some cases take years before seeing progress. That’s just how quickly the wheels of change turn, Echohawk said. We’re resilient. We never give up. And that’s really the history of native people ever since 1492,” he said referring to the date Christopher Columbus reached the Caribbean islands. On July 6, a U.S. District Court’s ruling called for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Lake Oahe easement for the Dakota Access Pipeline to vacate and remove all oil flowing through the pipeline by Aug. 5, while an environmental review is conducted. The federal judge’s decision stated that the easement to Energy Transfer Partners violated national environmental laws. The pipeline struck up protests throughout 2016 in North Dakota, led by the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. A portion of the $3.8 billion, 1,172-mile underground pipeline runs under South Dakota’s Lake Oahe, a source of drinking water for the Standing Rock Sioux. NARF was legal counsel to the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association and the National Congress of American Indians. NARF filed an amicus brief on behalf of the organizations in support of the plaintiff tribes: The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, the Yankton Sioux Tribe and the Oglala Sioux Tribe. Echohawk was the first Native American to graduate from the University of New Mexico School of Law in 1970. He attended on a scholarship funded by the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity, an agency that oversaw the War on Poverty programs during President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration. His Federal Indian Law classes taught him about the legal protections he had as a young Pawnee man. “This is all new information that none of us had before. And we realized that our tribal leaders didn’t really know all this, either,” Echohawk said. “We had a lot of rights that just were not being recognized or enforced.” He said that nonprofit groups that focused on legally defending specific demographics, including the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, highlighted the lack of counsel for federal Indian law. Shortly after graduating in 1970, Echohawk was asked to join a pilot program to bring legal services to Indigenous clients by the California Indian Legal Services, funded by the Ford Foundation: the Native American Rights Fund. A year later, NARF broke off from CILS and moved to Boulder. Echohawk said Colorado is a good base for the organization, as it’s centrally located to several native nations. That same year, it established the National Indian Law Library next to the office. NARF grew from a handful of attorneys in the 1970s to a counsel team of 18 lawyers among three offices. The organization is working on at least 50 cases annually, Echohawk said. Echohawk said the pool of Native American attorneys and those practicing Indian law was shallow when he started his career. It has increased alongside awareness of Native American legal rights, he said. According to a report in 2015, The National Native American Bar Association “represents more than 2,500 American Indian, Alaska Native and Hawaiian Native attorneys throughout the United States.” For one of NARF’s newest attorneys, working for the legal team has long been her dream job. Jacqueline De León, an attorney out of the Boulder office, joined three years ago. As a child, her family said that she would make a good lawyer because she enforced order in their household. She found that calling for herself in her adulthood. Throughout law school, two clerkships and a position at a Washington firm, De León had an end goal of joining NARF, or what she referred to as a beacon of hope for Indian Country. “I was specifically working toward this organization,” De León said. “And I’m a member of the Isleta Pueblo and somebody who cares about Native American law. I know that NARF is the top organization in the world advancing the rights of Native Americans.” Most of her docket consists of Indigenous voting rights cases. A win for NARF in North Dakota wrapped up earlier this year. North Dakota tightened its voter ID law in 2013. New restrictions required individuals to present identification listing their residential street address. It’s common for tribal IDs to lack a residential listing, De León said. According to NARF, “This is due, in part, to the fact that the U.S. Postal Service does not provide residential delivery in these rural Indian communities. Thus, most tribal members use a P.O. box. If a tribal ID has an address, it is typically the P.O. box address, which does not satisfy.” In January 2016, NARF counseled a lawsuit filed to block the voter ID law on behalf of eight Native Americans. It was on the basis that the North Dakota law disproportionately disenfranchised Native American voters and violated the Voting Rights Act and state and federal constitutions. In 2018 NARF, Campaign Legal Center, Robins Kaplan LLP, and Cohen Milstein Sellers and Toll PLLC filed a separate but related lawsuit on behalf of the Spirit Lake Tribe and six individual plaintiffs. The North Dakota Secretary of State agreed to settle the two cases in February. The Secretary of State agreed to work with the Department of Transportation to develop and implement a program with tribal governments to distribute free nondriver photo IDs. The Spirit Lake Nation and Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed a binding agreement with the state of North Dakota in April. Once accepted, the state will consider tribal IDs valid and enforce the agreements from February. According to NARF, there are more than 7,000 residents of voting age between the two tribes. There are more limitations that hinder Native Americans from fully exercising their franchise, De Leon said. NARF released a 175-page study in June, “Obstacles at Every Turn: Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters.” The report uses 120 testimonies from nine public hearings between 2017 and 2018. NARF intended to celebrate its 50th anniversary at a gala set for May 4, but the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in NARF postponing until spring 2021. NARF’s official anniversary is in September, said Echohawk. Don Ragona, development director for NARF, has worked with the organization in different positions since the 1990s. His department oversees funds and donations to NARF. NARF requests legal fees from its clients, meeting any budget, but will work pro bono. Its board of directors, an elected group of Native American leaders, gives guidance on which cases should be pursued. Legal resources are concentrated in five areas: Preserve tribal existence, protect tribal natural resources, promote Native American human rights, hold governments accountable to Native Americans, and to develop and educate the public on Indian law. Ragona said NARF performs a cost analysis of considered cases. But once it takes on a case, the legal team sees it through no matter the time or cost. “Litigation cases can be very, very expensive, and when your adversary is sometimes the federal government, it could take a long time,” he said. He recalls NARF nearly running out of funds while working on the Cobell v. Salazar class-action lawsuit of 1996 to 2009. NARF was active from the first filing through 2006. The case was filed in federal district court in Washington to force the federal government to provide an accounting to approximately 300,000 individual Indian money account holders who had their funds held in trust by the federal government. “We almost went broke because we took on that fight, but it was so important that we froze salaries,” Ragona said. “Attorneys didn’t take vacations for years, but that fight was so important. And we took on that role as that modern-day warrior.” On Dec. 8, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law a settlement of $1.5 billion to the 300,000 account holders. Another $1.9 billion was made available to pay individual Indians who want to sell their small fractionated interests in their trust lands to the federal government to be turned over to their tribes. Financial donations are necessary to keep NARF afloat. Ragona said funding is raised through a mail program, gifts program, in-house administrative donations, foundations and support from native tribes. Despite financial pressure of COVID-19 on the country, donations remain steady, he said. He added that a pandemic doesn’t pause the threats to Native American rights. “It’s been wonderful in that even through this — and I’m sure in some cases a personal sacrifice — they still gave to the work that we do on behalf of Indian Country,” Ragona said. NARF’s legal team isn’t in it for the dollars. Melody McCoy, who has worked as a staff attorney for NARF out of Boulder since 1986, could have pursued a part of law that’s more affluent. She was a part of the Cobell case that almost depleted NARF’s resources. She comes from a family of lawyers, but her drive to complete law school didn’t arrive until she was introduced to Indian law at a clerkship as a first-year student. After her second year of law school, she practiced for a short time on Wall Street. “I made more money than I’d ever made in my life — this was back in the ’80s — and I hated it,” McCoy said. She is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and calls on the spiritual guidance of her ancestors and the spiritual leadership of her tribe when waiting to argue in the courtroom. McCoy believes in the points and arguments she makes, she said. “I could have gone into private practice out of law school, and I almost did. But then I came to NARF and I took a two-thirds reduction in salary to come here,” McCoy said. “And yet, here I am 34 years later, and I’m probably more satisfied with my work than 90% of my law school classmates who did go into private practice.” Echohawk called the development of NARF into a well-known entity with many courtroom wins over the last 50 years “a dream come true.” But there’s still a ways to go. Outside of legal advocacy, NARF puts resources into educating law students and professionals, elected officials and the general public on Indian law and Native American rights. Often, misunderstandings surround nation sovereignty and treaty rights, he said. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling on July 9 reaffirmed the jurisdictional boundaries of tribal nations in Oklahoma that are guaranteed by U.S. treaties from the 1800s. The 5-4 ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma decided that much of eastern Oklahoma is in Indian Territory. Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and Cherokee reservations sit within the eastern part of the state. NARF filed an amicus curiae representing the National Congress of American Indians — the oldest, largest and most representative American Indian and Alaska Native organization in the country — in a similar case, Sharp v. Murphy. The case centered around Patrick Murphy, a Creek citizen who was prosecuted by the state for a murder that occurred on Creek Reservation and sentenced to death row. For crimes within Indian Territory, defendants must be tried within the reservation boundaries where it took place or in a federal court. Sharp V. Murphy was heard during the 2018-2019 session but came to a halt after Justice Neil Gorsuch — a former Boulder County resident and judge in Colorado — recused himself, putting the decision in a deadlock. The recent landmark win followed the Murphy case. Jimcy McGirt, a Seminole Nation citizen, was prosecuted by the state of Oklahoma for sex crimes against a minor within Creek Nation boundaries. The Supreme Court decision solidified that reservations within Oklahoma were never disestablished. “We have substantial legal rights in this country under this legal system, and they were just going unenforced,” Echohawk said. “We’re gonna be able to enforce those and help educate people about our continued existence in this country. It’s a country made up of three governments: federal government, state and tribal governments. That’s what the USA is.” Why you should care even if you don’t smoke weed or eat edibles GFC: Grown Folk Conversations Imagine a plant that was found in Asia 500 BC and used by indigenous people around the world for medicinal reasons and part of religious ceremonies was made illegal in 1925 based on propaganda, rhetoric and racial bias against Mexican immigrants and Black people (sound familiar). That plant is cannabis. Imagine a country where almost 95 years later, the same plant is being used to help a wide variety of mental and physical ailments like cancer and epilepsy, anxiety and PTSD. Yet, it’s resulted in 700,000 people arrested, 85% are people of African descent (Black) or Hispanic even though they use the drug at the same rate as white people (who are 76% of the country’s population). That country is America. Now imagine you got caught and arrested without incident for having a small amount of marijuana/cannabis when you were 18 and you’re STILL incarcerated during the Covid-19 pandemic. Then, you discover that a white boy, same age with the same amount of marijuana in a neighboring suburb is graduating from college this year because he caught, but wasn’t arrested. Instead, his drugs were confiscated, he was given a verbal warning and allowed to go home. The police use their “discretion” to warn, fine or arrest a person and although the white boy has been caught 2–3 more times in college he’s NEVER been arrested or faced a major consequence at his school. Two kids same crime — totally different consequences and outcomes. Juvenile justice scholars confirm that this scenario is real and has played out thousands of times and is a major factor in why Black and brown boys 18–24 disproportionately have adult criminal records and why white males don’t have any criminal records and finish college at a higher rate. Did you know that if you have a criminal record with a felony drug or violent offence most colleges won’t accept your applications, you’re ineligible for college financial aid and low income housing? In several states, you also lose your voting rights and it limits job opportunities. Marijuana/cannabis is now legalized for medicinal and/or recreational use in 30 states including the District of Columbia and has created a multibillion-dollar industry that disproportionately benefits rich, white men like politicians who were once tough on drugs — like John Boehner. Imagine if American citizens were STILL being arrested and held in states where this plant is legalized — while thousands quietly die from Covid-19 everyday… Well, thousands of nonviolent drug offenders are in American jails and prisons NOW waiting to be released under the CARES Act, but they aren’t and thousands are dying. I’m appealing to every person and parent — imagine if one of these people were you or your child? How would you feel right now? For the record, I have never used marijuana or any illegal substance. I’ve just seen the devastation the war on drugs has had on my family and in my community. The racial and socioeconomic disparities with drug-related laws, regulation, enforcement, convictions and incarceration have destroyed a whole generation of poor, Black and Hispanic families. It’s time to make this right. On cannabis equity and finance Unfortunately, it’s very hard to get any statics on how many Black or minority-owned cannabis businesses there are, but we know it’s low based on several reports from Vice and cannabis activist groups in Colorado, California and emerging markets like Chicago. For example, in Chicago’s 2019 cannabis dispensary lottery, ZERO applicants were Black. Yet, the majority of men incarcerated for marijuana violations are Black. The biggest and most blatant racial injustice and intentional financial barrier to keep smaller, minority business owners out of the cannabis industry are vertical integration requirements and regulations. Vertical integration means that a business owner will need to prove they have the money and infrastructure to control and comply with EVERY aspect of the cannabis operation from seed to sale. This includes R & D, growing and cultivation, processing, packaging, marketing, retail sales and distribution, and tedious and dangerous money management (see below). I need you to understand that how bad and totally discriminatory this policy is! It’s like saying — you can’t open a bakery unless you can prove that you can grow, harvest, and process the wheat, and bake EVERYTHING in your own facilities, in compliance with USDA, local grow, harvest, transport and baking regulations just to enter the million dollar license lottery. But larger corporate bakeries are allowed to buy multiple licenses, so the smaller shops, bakers and growers never have a chance or are forced to work for the corporate bakeries and never own their own business. This government model is totally biased and creates corporate monopolies that freeze out essential small businesses. Barring smaller, niche businesses from any industry, stifles community based business and over all financial growth. Big businesses cause HUGE problems when they fail — like we’ve seen in the banking industry and now in our food supply chain during the pandemic. If several smaller, local and regional produce and meat farmers, processors and packagers were supported versus a few large companies — our food supply would be safer, more sustainable and easier to transport and distribute to communities. Right now a few small companies own everything and it’s not good for the economy. The business management issue is further complicated by the fact that the cannabis/marijuana remains a Schedule I illegal substance like heroin or LSD according to the federal Controlled Substances Act. This creates a dangerous misalignment with State and local governments and law enforcement. This loophole allows companies to open, but doesn’t allow legal marijuana companies to put their money in banks making them susceptible to robberies and raids. Imagine, you’re a smaller cannabis company that was lucky enough to get a license and open but because you don’t have political or celebrity connections or clout, the Federal government raids your business, arrests you and legally seizes your money and inventory. Well, this is really happening, but strangely not to any celebrity owned or politically affiliated cannabis businesses. Like a lot of government enforcement efforts, they tend not to go after the multimillion dollar companies and focus their efforts (and taxpayer funds) on raiding small businesses that don’t have the resources to hire a team of connected corporate lawyers to negotiate and advocate on your behalf. So again, the big corporations win… either knocking out or swallowing up the competition with the help of the federal government. This is not fair. There should be a law against this type of legal inconsistency which gives amnesty or autonomy to states where cannabis is legal. But for now, the scales of equity and justice favor rich, white people again. If you have a prior drug offense you can’t get a license to open a legal cannabis business and you need political connections and millions of dollars to get a marijuana license in most states. Cities like Philadelphia are having discussions about Racial Equity Solutions with politicians and social justice organizations to discuss the long term effects of systemic and institutionalized bias and racism that the war on drugs, mass incarceration and lack of equity, oversight and accountability in the police, court, education and employment systems and economic development programs. Most urban cities are seeing a greater educational and economic divide within and outside Black and brown communities and Covid-19 has deepened the gap by exposing how many people have limited access to computers and basic internet service. The legal revenue from cannabis could fund infrastructure projects to increase internet access to low income communities which support and empower communities. The expansion of opportunities for smaller businesses like local farmers, culinary cannabis artists, scientists, processors, packers and transportation could bring much needed revenue and jobs to boost local economies. Once the laws are aligned this would end cannabis related arrests, incarceration and raids which offer community and business stability. What can you do? 1. Get informed and understand the injustice and bias in the creation and implementation of the Cares Act, the war on drugs and cannabis legalization, licensing and vertical integration policies (see links below) 2. Know your local and State representatives position and policies as it pertains to legalization and drug related criminal justice reform. Then call, email or reach out via social media and ask them what are they doing about releasing non violent inmates and ask them not to support vertical legalization 3. Push for the Federal government to remove cannabis from the Controlled Substance Act and make “vertical integration” stipulations on make licenses accessible to small businesses along the supply chain and limit licenses to larger corporations to avoid monopolies and make the cannabis business more diverse, sustainable and equitable. 4. Advocate, write letters supporting clemency, pardons and parole and push for the release of nonviolent inmates Imagine a country that rights its wrongs by using this healing plant and the income it generates to help heal and revitalize communities that are still suffering decades later from the trauma of lives lost and families torn apart from the violent war on drugs… This small step can make a HUGE impact — if done right. It could replace blight with bright, green spaces for gardening and play and communal space, affordable, housing and fund much needed community based social, medical and mental health services (including crisis teams as first responders). The funds could also provide gap funding in K-12 and college funding and local jobs and entrepreneur opportunities… The possibilities are endless when inclusion and empowerment is the goal. Thank you for reading! I hope this piece helps you understand that regardless of your views on legalization, this plant has become a serious social justice issue that needs to be addressed. Sources

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/9747/juvenile-crime-juvenile-justice https://www.fd.org/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/cares-act https://www.britannica.com/story/why-is-marijuana-illegal-in-the-us https://www.factcheck.org/2019/07/biden-on-the-1994-crime-bill/ https://www.countable.us/articles/849-date-fdr-made-marijuana-illegal-81-years-ago https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/30/shrinking-gap-between-number-of-blacks-and-whites-in-prison/ https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/yw4pkw/weed-industry-equity-black-business https://blockclubchicago.org/2019/11/18/dispensary-lottery/ This Voices in Food story, as told to K. Astre, is from Dr. Carrie Kholi-Murchison. She’s an entrepreneur and growth strategist who leads all of the diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives as the director of people and culture at Whole30, the popular elimination diet program. As someone who grew up eating from her grandfather’s garden and witnessed her mom and grandmother feed entire neighborhoods throughout her life, she understands that the conversation around food justice is just as much about building an equitable future for historically marginalized communities as it is about tapping into self and communal actualization.

On the history of food justice efforts within the Black community When we talk about the term “food justice,” I think there are lots of ways that people exclusively associate it with poverty and humans that have been forced to live in poverty, even though we have found ways to thrive. Black people have a long history of feeding each other, finding creative ways to nourish each other, using whatever privileges we have to move resources around and redistribute information to get more folks aware of our agency. Because of the multiple communities I live in and where I stand within the spectrum of those communities, I have seen white folks with power and money who are only looking at the work that needs to be done, in comparison to the Black and Indigenous folks who are actually doing the work. Not in a fancy, social justice way, but because they have been caring for their community for a very long time. On understanding structural inequities when it comes to food justice Society at large has capitalized on the human desire for convenience and this fast pace has really pushed us into letting other folks care for us and feed us. In many ways, Black people haven’t received the same kinds of information as other communities. If you look at the ways we are advertised to, marketed to and told what we can and cannot eat — those are justice issues as well. The way I try to think of it, and the way I try to get folks at Whole30 to look at it, is that it’s not only an issue of access but also awareness. I don’t mean awareness in the sense that some of us are uneducated, but because of the systems around us, many of us live very different lives and sometimes the information simply does not reach us. However, there are so many narratives that need to be fixed about Black food culture and our traditions. Yes, we have had to make do, but our food has not always been unhealthy. There are some habits that have been long-lasting because that’s what we have had access to as these are the brands that have catered to us. On the shortcomings of language to address systemic injustice As much as I love language, I feel there are too many ways we use it to erase the real meaning behind things. In my work, I frequently use the term “historically and socially marginalized,” but I use it in order to be able to make sure people are not using the term “minority” to address the fact that Black and brown people have been moved into these inequitable spaces by design. The ways I want people to understand historical marginalization is due to the habits that all of our privileges allow that have then pushed folks further and further away from the resources they need to live. Because I work with organizations that are white-run who are serving communities who are usually referred to as “underserved,” that’s a term that often comes up. I think that although we use those terms, we need to understand that they are really just euphemisms. It’s true that there are people who have been historically marginalized and underserved, but it leaves so much out and ignores the conversation of racial injustice if we fail to explain why or understand how these inequities came to be. On advocating for food justice in your own life I am always thinking high-level and visionary, but on a day-to-day level, we should always be thinking about how we can better care for and feed folks. The first step to beginning to think about food justice is on a micro level. Until we figure out for ourselves that we have choice around what we put in our bodies, trying to fix that on a macro scale will be difficult. For instance, let’s say that between your house and school or work, there is only fast food. Your schedule may dictate the food that you put into your body until you begin to separate yourself from your habits and look at food as not just something you’re eating but something that nourishes you. It’s how you care for your body. It affects not only your physical health but your mental health. Asking questions like, “Are there foods that can make me feel better?” and then really digging into why some people don’t have access to that food. Then you start figuring out who you need to start talking to. You can think about whether your community needs a garden. But that’s just an example. Not everyone wants to be in the dirt, growing food, but I encourage that curiosity and then leaning into where it takes you around your own food habits. On understanding your role in the fight for food justice There’s a big difference between charity or philanthropy and real justice that comes from eliminating the barriers to create an equitable future. The energy is different, the aim is different and the actions are different. It’s important for white folks to learn how to pour their resources into people that are already doing that work, as opposed to trying to come into it and taking over. When you give your money over to someone else, you are saying, “I trust you to solve this issue.” I see food justice the same as I see the need for other justice. It’s going to take a lot of us really digging in and focusing. I want to be fully actualized and I want to see other folks fully actualized. I want people to be free. I want them to be in control of themselves. But everyone doesn’t necessarily want to be able to grow their own food or be on a homestead. That means figuring out what your role is in your process of wellness. For me, growing food, figuring out ways to help people build a better relationship with food and helping to educate more people around food is important. I was intentional about working in this larger food industry because it gives me more connections to even more companies that have resources who may not be thinking about the communities they could be serving. BY MIHIR SHARMA CLARK RANDALL In St. Louis, the demand to defund the police has dovetailed with long-lasting struggles against cash bail and the abuse of prisoners. The Board of Aldermen’s passing of a bill that promises to start closing the city’s most notorious jail reflects the movement’s strength — but also the need for pressure to ensure that abolitionist demands are not watered down into merely cosmetic reforms. On June 29, the president of the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, Lewis Reed, filed Board Bill 92 — a motion to begin a process to close the city’s notorious Workhouse jail and reinvest the funds elsewhere. The Workhouse effectively operates as a debtor’s prison: it almost exclusively cages legally innocent residents, i.e., “nonviolent offenders” pre-trial, indeed for an average of 290 days. Their only offense is that they can’t afford cash bail. Formally called the Medium Security Institution (MSI), conditions in the Workhouse are squalid — and abusive. In 2009, the Missouri ACLU told of “endemic abuse of inmates” in the jail, reporting that guards regularly encouraged and organized fights among captives; in a 2013 survey of 358 jails by the Department of Justice, the Workhouse ranked third in reports of sexual misconduct by staff. The last five years have seen the death of six detainees inside the jail. Medical assistance is scarce at best, and outright neglect is common. In summer 2017, Heather Ann Thompson reported on the temperatures north of 110°F repeatedly endured by those trapped inside the Workhouse, without air conditioning. In one video, prisoners were heard crying out for help — after the footage went viral, protesters rallied outside the gates. Conditions in the jail have long sparked uproar. “We must say, in no way did we discover these things for the first time,” Blake Strode of the nonprofit civil rights legal advocacy organization ArchCity Defenders told listeners of his podcast Under the Arch. “You can trace litigation against the Workhouse back to the 1970s. It was like the same things had been happening for decades.” Indeed, already in 1975, revered St. Louis activist Percy Green, then the chairman of ACTION (Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes), wrote an op-ed in sharp opposition to the expansion of the Workhouse through a city bond issuance. In 1990, Clyde S. Cahill — the city’s first African-American district judge — filed a court order on the Workhouse and its conditions. Here, District Judge Cahill wrote, “The police have no trouble finding these offenders, they scoop them up from the corners of North St. Louis like shovelfuls of sand from a beach,” but, he added, “These persons are still men and women who are entitled to be treated with dignity as human beings.” So, the resistance in St. Louis is far from new. But it has picked up steam in recent years, and now even more so alongside national calls to defund the police and dismantle the carceral state. “At this point, where do we find the real change?” St. Louis organizer Michelle Higgins asked in a video interview with Jacobin. “It’s hyper-local.” Higgins is a leader with the Close the Workhouse campaign which she cofounded in 2018, and serves as the director of Faith for Justice and as pastor at St. John’s Church, where she continues to hold her revolutionary womanist sermons. The campaign to Close the Workhouse works closely with ArchCity Defenders, Action STL, and the Bail Project. “What we have been fighting for the last few years collectively,” Higgins said, “is control. Control through mass public education. And our work has been intersectional abolitionism.” Most of the organizers in these groups work at the regional and national level with the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), which has fortified a network of black organizers — both existing and new, to comprise over 150 black-led organizations. Their organizing recognizes the truth of Angela Davis’s argument that “prisons do not disappear social problems, they disappear human beings.” Donkey Capitalism “Thousands of hours, y’all, thousands and thousands of hours of canvassing, advocacy, and talking to people,” organizer at ArchCity Defenders Inez Bordeaux told an interviewer, “that’s what it took to finally get this legislation passed.” Bordeaux became a leader in the movement shortly after she was incarcerated in the Workhouse in 2016, when an error in the system left her with a probation officer who had left the department. Bordeaux’s crime was the failure to report to an officer who she could not report to. “I’m hopeful, but not quite celebrating,” she said. “We can’t let the city drag this out: no more writing reports and collecting data and all the talk. We simply refuse to step into 2021 with the Workhouse open — period.” Bordeaux and the coalition expressed only measured hopes in Lewis Reed’s Board Bill 92 when it was introduced, since it appropriated most of its proposals directly from movement demands. It initially called to have the Workhouse closed within six months and only half of the total current operating budget, i.e., $8.8 million, reinvested into crime reduction measures and reducing recidivism. But Reed managed to initially circumvent the amendment to close the Workhouse the activist coalition had been crafting and chose instead to legislate unilaterally. “Lewis essentially went out and copied our homework in an attempt to save face and take credit, but he still managed to miss on many points,” Bordeaux said. As well as their skepticism in the Democrat Reed, activists were troubled by loopholes in the language of the bill, as well as its timing. Reed has long been integrated into the city’s ruling elite, with ties to capitalist “special interests”; and his proposal does not represent a simple victory for the people of St. Louis or for movement leaders. After releasing Board Bill 92, Reed told local reports he “always supported” criminal justice reform. “First of all,” Higgins told us in response, “no he ain’t. We questioned him repeatedly about closing the workhouse in 2018 when he ran for president of the Board of Aldermen, and we organized the debates. His responses were worthless.” Indeed, in early 2019, in the run-up to those elections, Reed was the only candidate who refused to sign a pledge proposed by the coalition to definitively close the Workhouse. And even in the days and weeks leading up to his bill, Reed and his staffers publicly opposed such calls to shut it down. Bait and Switch On July 2, Reed finally introduced the bill to close the Workhouse, following a special meeting originally scheduled to discuss the city budget. While Reed’s bill might actually end up delivering part of what activists have been advocating for decades, they all note the bait and switch in the works. “It’s always been clear that Lewis [Reed] needed something big to cover up the airport privatization plan,” Higgins said. “We just never thought it would be closing the Workhouse.” The loose wording of the bill was widely criticized, most notably by ArchCity Defenders; indeed, the coalition introduced nearly a dozen amendment suggestions. “On the one hand, I am thrilled that the bill appears to be advanced,” Montague Simmons, a longtime organizer with the coalition told us, “but knowing St. Louis, the devil is always in the detail.” The bill as introduced did not necessarily guarantee the closure of the Workhouse, or respond adequately to the decades-long demands to address structural inequalities by reinvesting in public health, education, and social programs. The coalition’s amendments to the bill compensate for these weaknesses. The most successful amendments enforce participatory budgeting, allocation of local decision-making powers, and a holistic approach to addressing the needs of incarcerated persons. Thus the coalition managed to mold the bill closer to their original plan of radically reenvisioning the city’s “dangerous, deeply racialized, and violent definition” of public safety, as Mike Milton, director of the Bail Project St. Louis, called it. “So in early July, the strategy was twofold,” Higgins argued. “One, we asked alders to push [our] amendments. The second part was the power of the people to move elected officials who need to be unelected with the understanding that people power is strong.” Private Interests, Public Costs The airport privatization plan is, indeed, central to what is going on in St. Louis. It has been underway since at least 2017, when exiting mayor Francis Slay set the ball rolling, assisted by Grow Missouri, a nonprofit funded by Republican donors and St. Louis billionaire Rex Sinquefield. Public outrage ensued as Slay began the privatization process while mayor, and then his own law firm, Spencer Fane LLP, was hired to represent the potential buyers less than a year after he left office. Eventually, after a long fight, anti-privatization activists claimed victory last December when Mayor Lyda Krewson halted the process, citing the risk of any such sale, faced with the near-complete lack of public support. But with the deal apparently dead, tens of millions of dollars in consulting fees were left on the table — for they were only contractually obligated if the move were to go through. Many suspect that the key driving force behind the specter of privatization has reemerged: Sinquefield and his associates want to recoup what was owed from the city.At the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, Lewis Reed introduced Board Bill 71. If successful, this would make the St. Louis Lambert International Airport the second privatized airport in the US mainland (leaving aside the airport privatization in Puerto Rico). Lewis Reed and other city politicians have consistently proclaimed that the money from the sell-off will be used to address structural problems in the impoverished, overwhelmingly black neighborhoods on the North Side of St. Louis, long neglected by the city. Given the acceleration of the city’s existing fiscal crisis, its declining population, and increasing inequalities, privatization might appear as an attempt at damage control. “Theoretically, I understand the city and the North Side is in such dire straits . . . when you’re drowning, let’s be honest, everything looks like it could be a lifeboat,” Bordeaux said. “But we could do it a different way.” In light of Reed’s attempt to bury airport privatization with a call to close the Workhouse jail, a broad resistance front has been forming in St. Louis. The Close the Workhouse coalition, the anti-privatization activists at STL Not for Sale, union members with SEIU 1, and alderpersons seen as progressive are collectively resisting the false dichotomy put forth by some city officials. “Lyda [Krewson] and Lewis [Reed] — I think they have decided they can’t lose both fights,” said Josie Grillas, a member of STL Not for Sale, “so they wanted to make us choose: close the Workhouse or stop airport privatization. It’s best if they can pit us against each other.” But Bordeaux said the two coalitions are working together now. “We’re pretty much on the same page, now it’s a matter of figuring out what that looks like,” Grillas added. “Any chance we have to amplify the call to close the Workhouse, we need to do it. But we believe there is no choice here — we can win both.” Megan Green, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and alderwoman for the 15th Ward, has been one of the most vocal opponents in City Hall of the privatization of public assets in St. Louis. She argued: “While I disagree with privatization as a public policy option, now would actually be the worst time to privatize if you wanted to get the most amount of resources to such a deal in St. Louis city.” No industry has been more utterly grounded by the coronavirus than air travel, and St. Louis is no exception. “We have a lot of instances where privatization has not worked out in the public interest, whether it’s the water lines in Flint or the parking meters of Chicago, it has only worked out to make already rich people richer,” Green insisted. “Privatization,” Grillas said, “when it’s studied, has been proven to disproportionately harm Black women and communities plagued by divestment. This is neoliberalism or capitalism. Public-sector jobs have historically been a vector to the Black middle class — so as I see it, anti-privatization is an effective piece of antiracism work in St. Louis.” “It’s been very hard to build a sustained coalition,” Simmons told us. Since the legislative side of effecting policy changes goes through the bureaucracy of City Hall, sustaining any coalition would require a continued effort to work with alderpersons and city officials. Megan Green pitched in: “Most of the coalition that I am working with is in favor of closing the workhouse but also against privatizing the airport, and so we are going to have to keep our coalition together, both in the community and at the board to make sure that we can get the Workhouse closed but that we do not send forward a bill that would privatize our airport.” Theory in Action What does defunding the police mean? What does abolitionism look like? These questions were hotly discussed in St. Louis as across the United States following the tide of protests sparked by George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police. On Friday, July 17, 2020, the Board of Aldermen in the city of St. Louis unanimously passed Board Bill 92. Now that it seems certain the Workhouse is shut down, it remains unclear what might follow. The city’s larger jail, the Justice Center, has enough capacity to house the inmates currently in the Workhouse. “The reason for the emphasis on the Workhouse is that it’s a hellhole,” Jamala Rogers, leader with the Organization for Black Struggle told us. Montague Simmons agreed, insisting on the need for a wider conversation around the carceral system, including the city’s other jail: “We have heard Jimmy Edwards [the director of public safety] say explicitly that that is his cash cow — he keeps the Workhouse, so he can keep generating funds for the other facility.” But for Simmons, ending the mass incarceration of innocent people also demands an end to cash bail: “Even the courts were just outraged by the way that cash bail has been applied in the city. I think honestly it’s about time; that’s not just a local turn, that’s a national turn.” “The cash bail system is deeply racialized,” argued Kayla Reed in an interview in 2019. As Bordeaux has consistently stated, “If you are Black in St. Louis, either you or someone you know has been in the Workhouse.” Forty-nine percent of St. Louisans identify as African-American, and over 90 percent of the people in the Workhouse at any given time are African-American — the vast majority of them with an income under $40,000. Defunding the Police

The campaign to Close the Workhouse was inspired in large part by cofounder and executive director for Action St. Louis, Kayla Reed, who fundraised $17,000 in 2017 to help bail out black mothers of the Workhouse on Mother’s Day. She in many ways foresaw Board Bill 71, writing previously about the need to ensure “the opposition doesn’t co-opt our language to create a reality” that comes up short of their demands. But now, as she warned, the fight begins to ensure that the closure of the Workhouse doesn’t come alongside the expansion of the carceral apparatus elsewhere — as was the case when New York’s Rikers Island shut down, only for jails to be opened in each of the city’s five boroughs. Even the passing of the amended bill to close the Workhouse is testament to the industrious organizing by the city’s black-led coalition. The effort to close the Workhouse is part of a larger strategy to address the injustices of “the prison-industrial system,” as organizers with the campaign have repeatedly formulated. The larger abolitionist framework seeks to abolish the “criminalization of poverty,” Bordeaux insisted. Similar to other initiatives across the United States, defunding the police is also part of the local agenda for the coalition in St. Louis. The current St. Louis budget dedicates 53 percent to “public safety,” a large part of which consists of funding police ($234 million) and the carceral system. Reenvisioning this is central to the coalition’s goals. “We should rethink what it looks like for jail is not the first place a person lands,” Milton said. “We need to change the conversation from public safety to public health — what does the public need to be healthy, and what does community well-being look like?” “Some abolitionists make the argument of moderation: one goal post at a time,” Higgins said. “Either way, the thing that will create generational or legacy changes is undoing the criminality of the budget itself.” What is clear is that the efforts of the organizers and activists have been essential to transforming both the discourse and the material conditions toward these ends. As Thomas Harvey of the Advancement Project put it, “because everyone realizes the law isn’t going to set everyone free, it is going to be other people doing it.” “I just don’t understand why it’s the city’s largest asset, our airport, that they are willing to sell off for the next fifty years,” Bordeaux concludes, “when we could literally just defund the police.” By Lance Dixon on July 21, 2020

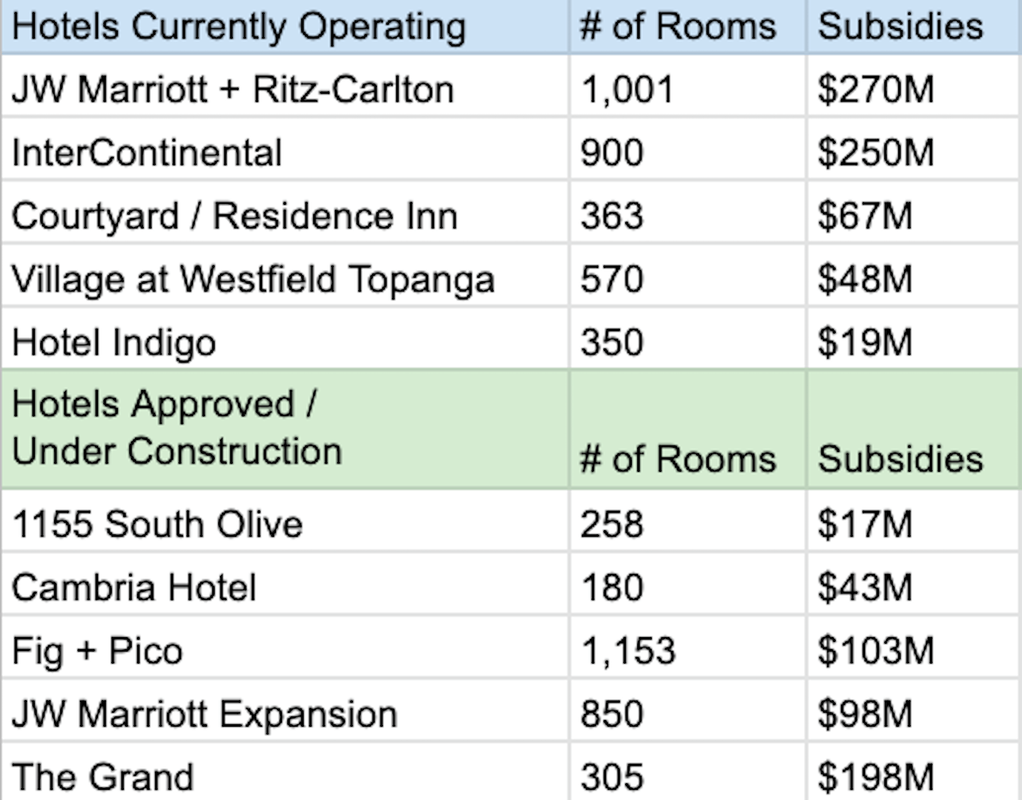

I’ll spare any readers of this post the rehashing of the lengthy rolodex of Black death that has happened in this country as a result of police violence, armed vigilantes or the failures of similar systems. But these names are obviously very much on the minds of people taking to the streets, having tough conversations with loved ones and calling for substantive changes to existing structures (both literal and figurative). In the middle of all of this I find myself, a millennial Black man working in the news industry, trying to simply navigate my day-to-day life without feeling waves of any mix of these feelings: guilt, anger, remorse, frustration, disappointment, sadness, fear, anxiety, helplessness, strength, pride and courage. Because the rolodex of names—which sadly continues to grow or be raised into the public consciousness—is not new. Being faced with the list of names, images, stories, videos, cries and screams doesn’t create a new wave of emotion. It’s the latest in an ocean I’ve been wading through as I approach a decade as a professional journalist. I’ve worked and lived for most of my life in Miami and grew up in neighborhoods that often attracted negative attention for gun violence. My family members also spent much of their early years in, and were impacted by, poverty and gun violence. And I spent several years as a reporter covering so many of these instances of violence—many of them near streets I played on, near my high school, near my aunts and uncles’ houses or not far from where my grandma used to live. All in all—and it shouldn’t impact whether these situations are any more or less tragic—I see faces that look like me trying to make the most out of their circumstances, trying to build up these places, and trying to make the most of what is often a highly inequitable, unaffordable and divided city. That story isn’t exclusive to Miami; it’s true from Minneapolis to New York to Louisville to Seattle. And so these names and situations stick with me because they aren’t just tragedies that happen at a distance, they are added to so many other names I’ve become familiar with here in South Florida. The names I can’t shake every time I have to #SayHerName or see another beautiful image made out of the smiling face of a young person whose life was taken before they could stand trial or simply make it home. Three names in particular hit me every time: Lavall Hall. Tequila Forshee. James T. Anderson. Lavall was a 25-year-old man with mental health issues who was killed by Miami Gardens police officers. Miami Gardens is a large, mostly suburban and predominantly Black city in South Florida, which I covered for most of my four-and-a-half years as a reporter at the Miami Herald. This case riled up people locally as activists called for the release of body-camera footage, pleaded for charges to be filed and ultimately, watched as neither of the officers involved in the case were ever charged. Tequila was a pre-teen simply getting her hair done before the start of her school year when she was shot and killed in a drive-by as people opened fire on the home she was sitting in. Nearly seven years later, no one has been arrested or charged in that case. James was my classmate. He was also the unintended victim of a shooting and he died when I was a sophomore in high school. My graduating class ultimately paid several tributes to him but I can’t ever shake the feeling of the texts I got from friends and the sadness that swept all of my classes when we went to school that Monday. I think of all these names, and highlight them, as a way of saying that Black reporters are walking into covering these stories with all kinds of experiences and lasting trauma that many of our non-Black, and non-BIPOC colleagues just don’t know and can’t speak to. And that’s not a slight to reporters who have navigated conflict zones, queer people having to write about the abuses and injustices brought on members of their community, crime reporters who have talked to many families of victims just like the ones I’ve named, or myriad other examples that I know are scarring for the people who have lived through them — and kept reporting. There’s just something different for me when I see the cries of mothers (who look like my mom) and partners and family members of victims at press conferences. Or when I see the words of exasperated community organizers as I’m editing stories about local responses to these cases. As I read the stories of so many people reckoning with their past mistakes and missteps in overlooking the experiences of Black professionals, I can’t help but see myself in my science class as a 10th grader wondering if things would change so there wouldn’t be more James Andersons. Or sitting in the home of Tequila Forshee’s father, years after her death, as he grappled with the loss of his daughter. A daughter who lives in the same city as my younger cousin, a bright young girl who has just been fortunate not to have something like this happen. And wondering if things would change. Or I think of sitting in Miami Gardens City Hall as protesters came in demanding justice, and then sitting in the newsroom as my colleague finished up a story noting that the officers wouldn’t be convicted of any wrongdoing. And wondering if things would change. And some potential progress has been made in recent months. More and more folks are taking sharp new looks at systemic racism while calling into question the structure, funding and ideology behind police departments. There’s also been much greater consideration for changing the way Black reporters talk about and share their experiences, without fear of being seen as biased. But when you see a Black person still struggling with “these times,” and wonder why they can’t just shake it, know that there’s so much more there and it didn’t start with George Floyd, or Breonna Taylor, or Elijah McCain, or Riah Milton, or Ahmaud Arbery, or Philando Castile, or Corey Jones, or Dominique Fells, or Eric Garner, or Trayvon Martin, or Sean Bell, or Rodney King, or Arthur McDuffie, or… Tens of thousands of people in Los Angeles County are at high risk for becoming homeless after the temporary halt on evictions is lifted—one of the largest mass displacements the region has ever seen.  Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the numbers have been dizzying. Infection rates. Deaths. Unemployment claims. The numbers tell the story of structural racism, with rising burdens of disease, death, and dispossession borne disproportionately by Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities. They reverberate through the national uprising for Black lives and racial justice, which also recounts numbers—of killings and excessive force by police, and of the millions of dollars allocated to bloated police budgets. We, too, are concerned with numbers. Ponder this: In January 2020, prior to the economic and social devastations wrought in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, 66,436 people were experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County, a region with approximately 10 million people. Seventy-two percent of them were unsheltered. Our UCLA colleague, Gary Blasi, estimates that once the halt in evictions due to the COVID-19 emergency is lifted, 365,000 renter households will be in imminent danger of eviction in Los Angeles County. Of these, as many as 120,000 renter households in Los Angeles County, including 184,000 children, are at high risk of not only being evicted but also becoming homeless. The lowest projection provided by the Blasi report is 36,000 newly homeless households, including 56,000 children. This will be one of the largest mass displacements to unfold in the region. Meanwhile, Los Angeles, emblematic of the inequalities that structure life and death in the United States, is gripped by political inertia. Public officials at all levels of government have failed to enact policies that would protect tenants from displacement. In 2018, the Economic Roundtable reported that nearly 600,000 Los Angeles County residents were not only in poverty, but were also in households spending 90 percent or more of their income on housing. That was in the time of robust employment and somewhat stable incomes. Now these households are on the brink of disaster, having to make the choice between food or rent, most likely unable to afford either. Where will the currently unhoused and the newly unhoused go? Decades of disinvestment in low-income housing and investment in policies of gentrification and luxury urban development have created a crisis of housing insecurity that now conjoins with the political failure to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. The construction of new affordable housing in Los Angeles has been excruciatingly slow, and the waiting lists for housing vouchers are painfully long. But here’s another set of numbers. There are over 100,000 hotel and motel rooms in Los Angeles County that serve tourists. Hotel industry estimates indicate that, given the downturn in the global tourist industry, around 70,000 of these rooms will lie vacant for several years to come. Moreover, many hotels and motels will most likely never recover because of their debt structures. Such distressed properties will most likely be bought up by Wall Street actors such as the Blackstone Group, which went on a buying spree in the wake of the Great Recession and purchased budget motel chains such as Motel 6. Especially vulnerable are the neighborhoods that are already on the front lines of gentrification, where property ownership is shifting from communities to corporations. Often places with long histories of exclusionary and predatory finance (redlining and subprime loans), these were hotspots of foreclosure during the Great Recession. In this round of crisis, they are at risk of more wealth loss. The public already has a stake in the county’s hotels. A chunk of these vacant rooms are in publicly subsidized hotels, or hotels whose development has relied on public sector investments, financial incentives, tax rebates, and deferrals, as well as land assembly through eminent domain and redevelopment. Just in downtown Los Angeles, the financial costs of such subsidies amounted to $1 billion between 2005 and 2018, and the city has committed at least $114 million more since then in poorly negotiated deals. These numbers, of course, do not include the incalculable human costs of displacement nor the impact of diverting these resources away from the provision of housing, schools, libraries, parks, and many other necessities that LA’s working-class communities of color sorely lack. And what did Angelenos get in return for these gigantic corporate handouts? Increasingly unaffordable, over-policed neighborhoods. The largest subsidy, a whopping $270 million for the Ritz-Carlton and JW Marriott at LA Live, was gifted to AEG to create 1,001 rooms, representing roughly 1 percent of the overall county stock. At the same time, many of our local officials are embroiled in obscene developer-driven corruption scandals, in addition to the influence that developers openly wield at City Hall, while homelessness and housing precarity have skyrocketed. In our recently released report, “Hotel California: Housing the Crisis,” we do the math. Inspired by housing justice movements that have drawn attention to the cruel paradox of vacant property while thousands of people experience homelessness or housing insecurity, we advocate for the public acquisition of vacant tourist hotels and motels in Los Angeles and a shift in their use from hospitality to housing. Here is the opportunity to significantly enact the mass expansion of low-income housing, and to even convert such property into social housing. No other existing mechanism of housing provision in Los Angeles can add this many housing units at a reasonable price point and in a relatively compressed timeline. The time is one of reckoning. As the national uprising for Black lives and racial justice intersects with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear that the human suffering, so poignantly visible through protest and outrage, is state-sanctioned and never inevitable. It represents a conscious policy choice. But it does not have to be this way. In Los Angeles, as in other U.S. cities, publicly subsidized hotel development has been underwritten by what urban studies scholars have called “geobribes”—largesse from public coffers distributed to global corporations and real-estate developers in the (rarely met) hope of spurring economic benefits. Accompanying such subsidies have been institutional forms of displacement and social cleansing, from Business Improvement Districts to zero-tolerance policing. It is time to redirect public resources and public purpose tools such as eminent domain for housing, especially for Black and Latinx communities where public investment has primarily taken the form of policing and where the devastation of impending evictions will be most acutely felt. Spatial justice is the urgent task at hand. If it does not seem possible to imagine the acquisition and conversion of vacant tourist hotels and motels into social housing, then it is worth reflecting on how the present moment of compounding crises has broken past the limits of the possible. In California, Project Roomkey is both a statewide and local program to use vacant tourist hotels and motels as shelter for people experiencing homelessness during the pandemic. In Minneapolis, amid the protests following the murder of Mr. George Floyd, who himself worked as a security guard in the state’s largest homeless shelter, the unhoused came together to create a community in a vacant Minneapolis Sheraton Hotel. The Minneapolis experiment was short-lived, and because Project Roomkey is reliant on negotiated occupancy agreements with hotels rather than on the commandeering of property, an emergency power that rests with government executives, it has failed to meet its targets. But both hint at what could be possible with more political will. The relationship between property and housing is a complex one. From Indigenous dispossession to financial speculation, it has been a key logic of inequality in the United States. But the vacancy and indebtedness of property presents an opening to reconsider its use and ownership for a social purpose: housing. Ananya Roy is professor of urban planning, social welfare, and geography at UCLA and director of the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy. Her research and scholarship is concerned with housing justice and racial justice. Jonny Coleman is a writer and organizer with NOlympics LA. In many states, transgender people face hurdles to voting and other discrimination to which the amendment could apply. Newly 18 years old, Oliver was thrilled to cast a ballot for the first time. At his voting location in a Maryland suburb of Washington, D.C., Oliver presented his identification when asked for it by a poll worker. This couldn’t be Oliver’s ID, the poll worker claimed, because the card indicated that Oliver was female. But Oliver identifies and presents as male; he is one of the 1.55 million transgender people in the United States. Jody L. Herman et al., Williams Inst., Age of Individuals Who Identify as Transgender in the United States (Jan. 2017). Although Oliver had legally changed his name, he had not updated his ID to reflect his gender identity because doing so is “a really expensive process,” as he recounted to NBC News in 2018. Julie Moreau, Strict ID Laws Could Disenfranchise 78,000 Transgender Voters, Report Says, NBC News, Aug. 17, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/strict-id-laws-could-disenfranchise-78-000-transgender-voters-report-n901696. The poll worker asked Oliver to step aside, and he was able to vote only after waiting an hour for poll workers to assess the situation. He felt humiliated, anxious, and discriminated against. Oliver decided that in the future, he would vote by absentee ballot to avoid a repeat scenario.