|

Across the country, the death penalty is in steep decline. But in September, the state’s attorney general sought execution dates for nine men, and its Supreme Court set dates for two of them.

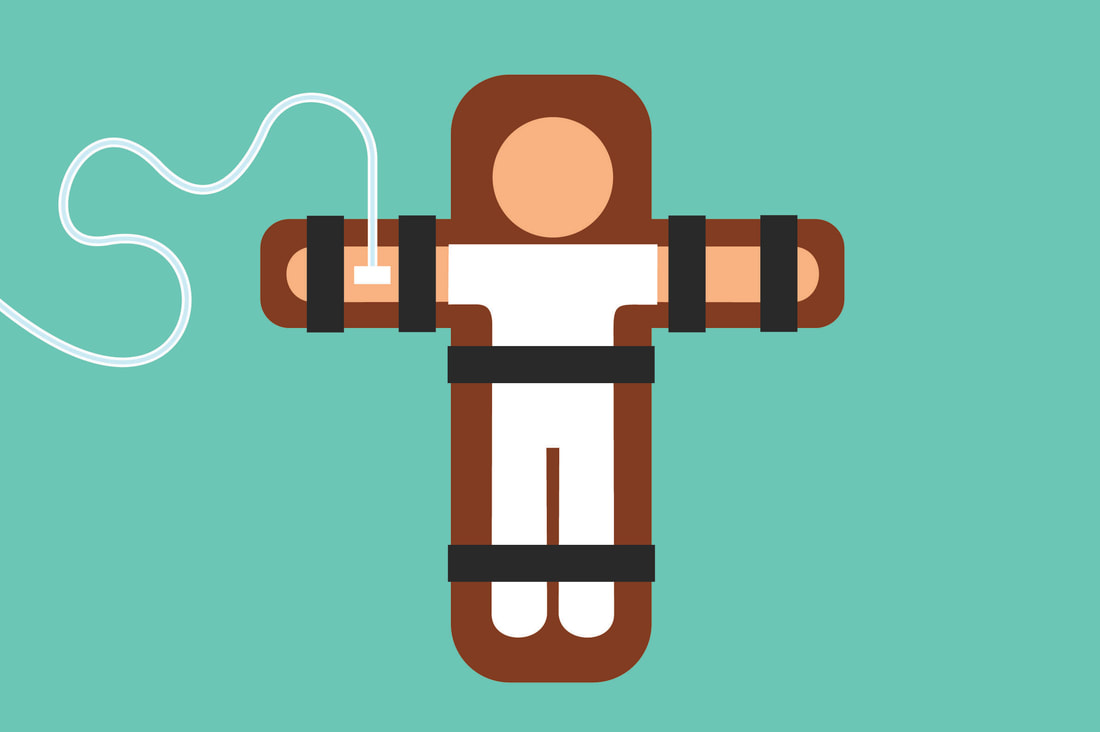

In April 1996, Tony Carruthers, charged with kidnapping and murder, stood in a Tennessee courtroom. Despite the severity of the case against him—he was charged with three counts of first-degree murder and faced the death penalty—he did not have an attorney by his side. Carruthers represented himself. Two years earlier, Carruthers and James Montgomery were arrested in Memphis, accused of killing Marcellos Anderson, his mother Delois, and Anderson’s friend Frederick Tucker. The three disappeared on the night of Feb. 24, 1994, and their bodies were found seven days later, buried beneath a casket in a local cemetery. By the time his trial began in 1996, Carruthers had gone through six attorneys. He asked to have another attorney appointed to him, but the judge refused. He was convinced that Carruthers was trying to delay his trial and forced him to proceed pro se, or arguing on his own behalf. Carruthers’s self-representation in a triple murder case was made all the more perilous by the fact that the state’s case against him relied heavily on the grand jury testimony from a career informant, Alfredo Shaw. The Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University’s law school issued a report finding that over 45 percent of all wrongful convictions in death penalty cases stem from lying by criminal informants, making “snitching the leading cause of wrongful convictions in U.S. capital cases.” Shaw’s story was deeply flawed; he said Carruthers confessed to him in a jail law library but later admitted he had not seen Carruthers since 1988. In a statement to local media before the trial, Shaw recanted his story. Prosecutors branded Shaw a liar and decided not to use him as a trial witness. But serving as his own attorney, Carruthers went forward with Shaw as a witness and, in a bumbling cross examination, mistakenly led Shaw to repeat his previously recanted testimony implicating him in the murders. On April 26, 1996, Carruthers was convicted and sentenced to death even though there was no forensic evidence linking him to the triple homicide. “The end of Mr. Carruthers pro se cross-exam of Alfredo Shaw is one of the most singularly inept, ineffective and disastrous cross-examinations, possible, one that seemed designed to secure not only a guilty verdict, but a death sentence,” Carruthers’s attorneys wrote in a post-conviction filing. Carruthers’s act of representing himself was so damaging that it eventually led to his co-defendant James Montgomery’s release. An appeals court granted him a new trial due to the prejudicial impact of being tried alongside a pro se defendant. In 2000, Montgomery agreed to a guilty plea to lesser charges of second-degree murder and was released in 2015. Nearly 24 years after the two were convicted, Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery requested that the state Supreme Court set execution dates for nine men, including Carruthers. In a Dec. 30 filing in opposition to the state’s motion to set an execution date for Carruthers, his attorneys with the Federal Public Defender for the Middle District of Tennessee wrote that by representing himself in court, he “did more to get himself convicted and sentenced to death than did the prosecution.” They also argued that Carruthers was incompetent to stand trial because he is seriously mentally ill “and that the manifestations of this serious mental illness include paranoid delusions, distorted thought processes, conspiratorial misapprehension of fact, a gross inability to make prudent decisions, and a complete inability to rationally perceive or understand the world around him. He also has significant brain damage which exacerbates the debilitating effects of his serious mental illness.” Carruthers’s case would be historic: If executed, he would be the first person in nearly a century to be put to death after being forced to represent himself at trial. Slatery’s request for a slew of executions in 2020 is so unusual because use of the death penalty is at near record lows. Death sentences declined from 298 in 1975 to 34 in 2019. Last year, 22 prisoners were executed nationwide, making it the second least active year for American death chambers since 1991. It was the fifth year in a row in which fewer than 30 prisoners were executed. For nearly a decade, Tennessee was part of this trend. The state didn’t execute a single prisoner from 2010 through 2017, although it did try. The state set execution dates for 10 men in 2014, scheduling regular executions between April 2014 and November 2015. All were called off because of legal challenges over the state’s execution methods. In early 2018, however, the death penalty returned to Tennessee. The state adopted a new lethal injection protocol, a three-drug cocktail that starts with the sedative midazolam. The protocol became notorious after it was used in botched executions in other states, including the execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014. After the midazolam was administered, Lockett struggled for several minutes, saying “something is wrong” and “this shit is fucking with my mind.” A nurse then closed blinds to observers and, according to The Intercept, “the blanket was lifted to reveal that the drugs were seeping into the tissue of his inner thigh instead of his veins, causing his skin to swell.” Officials called the governor’s office and then halted the proceedings—but by then Lockett was dead. Tennessee’s new protocol came with warnings from the state’s own consultants that midazolam might not be sufficient to prevent a person from feeling the effects of the next two drugs, vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride. The new protocol also prompted a legal challenge filed in February 2018 by 33 death row prisoners who argued that it would effectively torture them to death. That same month, Slatery asked the state Supreme Court to schedule executions for eight men and asked that all the dates be set before June 1 due to concerns about the acquisition of execution drugs. That request was denied, but the court did start scheduling men to die, albeit on a slightly slower timeline. Beginning with the execution of Billy Ray Irick on Aug. 9, 2018, Tennessee executed six men in less than 16 months, second only to Texas during that timeframe. Each of the men—Irick, Ed Zagorski, David Miller, Don Johnson, Stephen West, and Lee Hall—had a history of mental illness, childhood abuse, or both. West was being treated with powerful antipsychotic drugs up until his execution, and Hall was functionally blind. Another condemned man, Charles Wright, was spared only because he died of cancer months before his execution date. The next man scheduled to die in Tennessee is Nick Sutton, who is set to be executed in the electric chair on Thursday. In 1985, Sutton was sentenced to death for fatally stabbing a fellow prisoner. When the murder occurred, he was serving a life sentence for murdering his grandmother when he was 18 years old. In his request for clemency, submitted to Governor Bill Lee in mid-January, Sutton’s attorneys included affidavits from two former correction officers who describe incidents in which Sutton saved their lives. “I owe my life to Nick Sutton,” wrote former correction officer Tony Eden in one affidavit. Several members of his victims’ families support Sutton’s clemency effort, and Sutton’s case garnered the attention of legendary anti-death penalty activist Sister Helen Prejean who tweeted on Jan. 22 that “he has saved the lives of three different prison staff members. Nick Sutton should not be executed.” In a letter to the Tennessee governor accompanying the clemency request, Sutton’s attorney wrote that Sutton “has gone from a life-taker to a life-saver.” Tennessee’s execution spree comes as death chambers in formerly prolific death penalty states are dormant, with some even considering abolition. On Jan. 7, Louisiana marked a full decade without an execution. Oklahoma—which has carried out 112 executions since 1976, trailing only Virginia and Texas—has not executed anyone in five years. In mid-January, an Oklahoma state representative introduced House Bill 2876 which would abolish the death penalty. If the bill passes in the House it will join 21 other states that have abolished the death penalty. Although Tennessee is bucking the national trend regarding executions, the state’s prosecutors and juries have become reluctant to hand down death sentences. It has been more than 25 years since Tennessee juries sentenced more than 10 people to death. In the last five years, only one death sentence has been handed down. “Death sentences are a better indicator of public sentiment about the death penalty than executions are,” Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told The Appeal. “When you have a state in which there’s been one new death sentence in the last five years, that’s an indication that juries are not returning death sentences. That’s an indication that the death penalty is withering on the back end while political actors are involved on the other end in executions.” Perhaps the most critical actor behind the resurgence of Tennessee’s death penalty is Slatery, who was appointed attorney general in 2014 by the state Supreme Court after he served as former Governor Bill Haslam’s top legal adviser. Dunham called Slatery “an extremist among extremists,” and Slatery appeared intent on proving his pro-death penalty bona fides in 2019. On Sept. 20, Slatery announced that his office would challenge an agreement proposed by Davidson County (Nashville) District Attorney Glenn Funk, in which death row prisoner Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman was re-sentenced to life because of prosecutorial misconduct during his 1987 trial. Attorneys for Abdur’Rahman alleged that John Zimmerman, then an assistant district attorney, excluded Black people from serving as jurors in Abdur’Rahman’s trial. In 2015, Zimmerman held a training in which he allegedly said that in a case with Latinx defendants, he “wanted an all African American jury, because ‘all Blacks hate Mexicans.’” When agreeing to the re-sentencing, Funk conceded that there was “overt racial bias” in Abdur’Rahman’s trial. Funk said, “The pursuit of justice is incompatible with deception. Prosecutors must never be dishonest to or mislead defense attorneys, courts or juries.” Nashville Criminal Court Judge Monte Watkins agreed and said the deal would “remedy a legal injustice.” The challenge to the re-sentencing was a remarkable step aimed at overturning an agreement between a prosecutor and a judge. Abdur’Rahman was scheduled to be executed on April 16, but last month the Tennessee Supreme Court granted him a stay while the legal fight over his case continues. Slatery challenged the deal with Abdur’Rahman on the same day that he asked the state Supreme Court to set execution dates for nine men, including Carruthers. In mid-January, the court set 2020 execution dates for two of the nine—Harold Nichols on June 4 and Oscar Smith on Aug. 4—and there most likely will be more coming soon. In October, Slatery spokesperson Samantha Fisher said the office held off on filing motions to schedule execution dates because of litigation over execution methods. With that legal challenge resolved, she said, Slatery decided to file the nine motions at once. Fisher also contends that the requests for execution dates are not a matter of Slatery’s discretion. “The attorney general, by rule of the Tennessee Supreme Court, is ordered to file a motion in the Tennessee Supreme Court notifying the court of the status of a defendant’s litigation once the three-tiered appeals process has been exhausted,” Fisher told The Appeal. In court filings at the end of last year, Kelley Henry, a supervising assistant federal public defender who represents seven of the nine prisoners for whom Slatery sought execution dates, argued that four of the men lack the capacity to rationally understand that they are going to be killed, or why. Carruthers is one of them. When a forensic psychiatrist attempted to assess Carruthers, he declined to see her “and demanded her insurance paperwork so that he can be paid $3.3 million for her malpractice in attempting to see him,” according to the Dec. 30 filing from his attorneys. His attorneys also wrote that another psychiatrist observed that Carruthers believed his attorneys were involved in a “vast conspiracy within the legal system involving homosexual themes” and that he demanded “millions of dollars which he persists in believing the government owes him.” Carruthers’s case is reflective of the systemic issues with the death penalty, including the pervasiveness of mental illness in the condemned and the cluster of outlier counties pursuing the punishment. His case was heard by a jury in Shelby County (Memphis), which accounts for nearly half of Tennessee’s death row despite being home to less than 14 percent of the state’s population. “Since 2001, only eight of Tennessee’s 95 counties have imposed sustained death sentences,” Carruthers’s attorneys wrote in their December filing. “And, of the nine trials resulting in a death sentence since 2010, five were from Shelby County.” “Each of these cases,” Henry told The Appeal, “is a window into the brokenness of the Tennessee death penalty.”

1 Comment

Earley Story

9/20/2022 01:29:38 pm

Alfredo Shaw called my home and told me that his life was in danger because the Shelby County Sheriff Department was alerted that he informed the law enforcement that he, was being forced to give false testimony in case # 97-08560. The court refuse to even give me an affidavit of Complaint of the 8-8-1997 arrest. Shaw even gave testimony in court under duress on 12-7-1999 before judge John Colton.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed