|

The economic slowdown brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a surge of rental evictions, leading to a ballooning of social and legal problems and calls for more access to lawyers to represent renters in eviction cases. At the American Bar Association Virtual Annual Meeting in August, the House of Delegates adopted policy urging governments to minimize evictions and financially assist both landlords and renters faced with hardship because of the pandemic. The new ABA policy expressed concern that if little is done nationwide there would be a significant destabilization of the rental housing market and a major eviction crisis.

Earlier this year, as the pandemic spread, courts, governors or legislatures in most states had imposed moratoriums on evictions, essentially delaying legal proceedings. Since then, the national landscape for evictions has changed, with 31 states now lacking any eviction moratorium, according to panelists at last week’s 2020 Equal Justice Virtual Conference. The conference, which ran Aug. 11-13, was co-sponsored by the ABA Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service and the National Legal Aid & Defender Association. In a panel, “Right to Counsel in a World Gone Mad: Evictions During and After COVID-19,” panelist Emily Benfer, a health and housing expert and visiting law professor at Wake Forest University School of Law, warned that 30 million to 40 million Americans are at “risk of eviction right now” if no additional governmental assistance is provided. Aside from financial assistance to renters and landlords, another effort to combat the rise of evictions, which is already law in a handful of U.S. local jurisdictions, is to expand a guaranteed right to counsel for low-income renters. In eviction proceedings, most landlords have lawyers, and research shows that unrepresented tenants usually lose their cases. “Providing a lawyer makes a tremendous difference in keeping people in their homes,” said John Pollock, a housing advocate who moderated the conference program. Evictions, he noted, lead to homelessness with a resulting host of social problems related to the health and welfare of individuals and families. “This is a right that can really make a difference,” Pollock added.

0 Comments

WASHINGTON ― The U.S. Census Bureau unexpectedly announced it will end 2020 census field operations early, a decision that will disproportionately hurt Native American tribes that are already historically undercounted, hard to reach and rely on accurate census data for lifesaving federal dollars.

The agency slipped the news into a press release last week: “We will end field data collection by Sept. 30, 2020. Self-response options will also close on that date to permit the commencement of data processing.” That’s a month earlier than the Census Bureau ― and any organization focused on a strong census count ― planned for all year. So what? It’s only a month, right? And why does the census matter anyway, beyond showing us how many people live here and where they live? The census is so much more than a headcount. Census data is used to draw congressional districts, which means, for example, the more that minorities are counted in a given area, the more likely they will be kept together as a community and have a voice in Congress. If fewer minorities are counted in a given area, those communities are broken apart and lumped into other districts. Census data is also used to decide how much federal money goes to every community. For each person who isn’t counted in the census, their community loses thousands of dollars every year for the next 10 years. That money would have otherwise been used for services like health care, education, infrastructure and housing assistance. Native Americans were the most undercounted population in the country the last time the census was taken in 2010. This time, it’s going to be even worse because of the Census Bureau’s decision to close up shop early. Why? People in remote areas, like many tribal communities, often rely on census takers coming to them in the final stage of data collection to do “nonresponse follow-ups.” They knock on the doors of people who haven’t responded to the census online or by mail, and they interview them. Many people on reservations don’t have internet access or reliable mail, so they get counted in person. But because of the coronavirus pandemic, reservations closed to the public for months. Now, with census field operations cut short, census takers simply won’t reach some of these communities at all. “It ensures a historic, devastating undercount for Native Americans,” said Natalie Landreth, senior staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund. “It ensures it. We’re not guessing. We’ve run all the numbers, and we know it.” Tribes in remote areas rely entirely on federal dollars for health care, which the federal government is required to provide to millions of Native Americans under its treaty obligations. A census undercount means they will get a fraction of the federal money they are owed for the next 10 years, in an already chronically underfunded health care system overseen by the Indian Health Service, amid a pandemic that has ravaged tribal communities. Native Americans have long been undercounted. The official estimated undercount in the 2010 census was 4.9%, though Landreth said it was likely closer to 7%. But this year’s pandemic and the Census Bureau’s shortened timeline mean tribes will take a bigger hit. “It’s going to throw people who are already poor into more extreme poverty and diminish their political power so you never get anybody who represents your interests,” Landreth said. “Think of being powerless and poor. That’s what this does.” The 2020 census response rate is trackable on the Census Bureau’s website. It currently shows a 63.6% response rate nationwide among people who responded online, by mail or by phone. If you toggle the data, it shows a 20.5% response rate among tribes. "Think of being powerless and poor. That's what this does." Natalie Landreth, Native American Rights Fund In Alaska, which is home to 229 of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the country, the level of census data collection among tribes sounds abysmal. The state is so big and some tribes are so remote that census takers typically head into communities as early as January, much earlier than in the rest of the country. But bad storms early in the year delayed the process. That was followed by tribes’ shutting down for months because of the pandemic. Now that it’s August, a lot of locals aren’t home. They’ve left their villages for weeks of fishing and hunting as part of the seasonal subsistence cycle. On top of that, the Census Bureau sowed confusion among Alaskan tribes about how census data would be collected this year, said Nicole Borromeo, executive vice president of the Alaska Federation of Natives. “They had been trained to tell rural residents that they could only do it in person. Now they’re being told they can do it online or over the phone, when they had neither option before,” she said. “Then they said they’d be back in person. But instead, they’re just mailing them flyers and postcards. Then they said field operations are going to last through October. Now all of a sudden they’re ending at the end of September.” It doesn’t help that there is already a massive amount of distrust of the federal government among tribes due to decades of oppression and broken promises. “This could not be any worse for Alaska,” Borromeo added. Three major tribal advocacy groups last week issued a rare joint statement sounding the alarm on the Census Bureau’s “unwarranted and irresponsible decision” to cut short the census count. “Our tribal nations and tribal communities have been ravaged by COVID-19, and an extension of the census enumeration period was a humane lifeline during an unprecedented global health catastrophe that provided critically needed additional time to tribal nations to ensure that ... everyone in their communities are counted,” said the statement from the National Congress of American Indians, the Native American Rights Fund and the National Urban Indian Family Coalition. “For millions of American Indians and Alaska Natives, whether they live on rural reservations or in America’s large cities, an inaccurate census count will decimate our ability to advocate for necessary services for our most vulnerable communities.” The groups urged Congress to include language in the next COVID-19 relief bill to require the Census Bureau to stick to its original Oct. 31 deadline to end field operations. There is some support for this on Capitol Hill. Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) wrote to House and Senate leaders Tuesday urging them to extend the statutory deadlines to deliver census data to the president and states to the spring of 2021 from Dec. 31. That would extend the entire census process, not just field operations, which is what some census officials have said they need to do an accurate census count. “In July, the associate director of the census, Albert Fontenot, said, ‘We are past the window of being able to get those counts’ by year’s end,” said the letter from Murkowski and Schatz, which was signed by a total of 48 senators. “Extending the deadlines for the delivery of these files in the next COVID-19 relief package will ensure that the Census Bureau has adequate time to complete a full, fair and accurate 2020 census.” But congressional leaders are nowhere near a deal on the next COVID-19 relief bill. Congress doesn’t even return from a break until September. And in a depressing sign that the census itself has become a partisan issue, only two of the 48 senators who signed the Murkowski-Schatz letter are Republicans: Murkowksi and fellow Sen. Dan Sullivan of Alaska. HuffPost could only find one other GOP senator, Steve Daines of Montana, who publicly urged the Census Bureau to extend its deadlines. A spokesperson for Sen. John Hoeven (R-N.D.), who chairs the Committee on Indian Affairs, did not respond to a request for comment on whether he is concerned about census field operations ending early and hurting tribes. Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-Ariz.), chairman of the House Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States, said there’s only one reason why the Census Bureau is closing up shop early. “This is all politically motivated,” he said. “This is about Republicans trying to keep control over a changing demographic that they just can’t keep up with. ... Republicans understand if the census data comes back strong, when it comes to reelections, they’re going to have an even harder time holding power through a gerrymandered district.” It makes no sense to stop counting people early, and all signs point to corruption within the Trump administration, Gallego added. “They could ask for more money if they wanted,” he said. “They have given us no real reason for this. They’re just not going to count.” A Census Bureau spokesperson responded to a HuffPost request for comment by emailing a link to the agency’s press release announcing its plans to end its field operations early. The spokesperson did not respond to a follow-up email asking if politics are driving the agency’s decision. With Congress gone and hardly any Republicans making the issue a priority, there’s nothing stopping the Census Bureau from ending its count early. Unless something changes, tribal villages and reservations already wrestling with poverty and health disparities will have to brace for even fewer federal resources for another 10 years. “This is harming their day-to-day ability to live for the next decade,” Landreth said. “I’ve never seen anything like this.” This article originally appeared on HuffPost. By Shari Silberstein

In the last few weeks, hundreds of thousands of us took our grief, trauma and rage onto the streets, online, and into public hearings to protest the ways that this nation devalues, demeans and destroys the lives of Black and Brown people. Violence against people of color is at the core of U.S. history. From the genocide of Native Americans to slavery and Jim Crow, to today’s Black Americans who live in fear every day — George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Nina Pop are just a few recent victims of our national epidemic of violence and racism. Policing’s role in this brutalization is not new. Police enforced slavery, enabled lynchings by white mobs, enforced Black Codes, and continue to criminalize Black and Brown kids in our schools for the same behavior that gets white kids a mere warning. In short, policing as a system has always upheld white supremacy, no matter how many individual officers act in good faith. By now, it is clear that our justice system, including policing, must transform. Transformation cannot happen without accountability—for the present and the ugly past. But what does that look like in practice? Most people use the term “accountability” to mean punishing people for doing something wrong. Our legacy of racism positions Black and Brown people as always suspect of wrongdoing. This leads to over-policing, mass incarceration, and devastation and trauma for communities of color. At the same time, this model of accountability almost never applies to police violence. In most of those cases police don’t even lose their jobs, much less go to prison. An anti-racist vision of accountability repairs harm instead of causing more of it. This process, modeled on restorative justice, begins with the essential step of acknowledging and taking responsibility for the harm. From there, accountability continues with additional steps to make things right and prevent future harm. Owning the full weight of hurting another sounds so simple. But it is, in fact, terrifying. Humans avoid it with all kinds of mental and verbal gymnastics. How many times have you heard someone downplay slavery as a thing of the past? Our nation has never fully acknowledged the centuries-long impact of slavery and its corollaries on the health, socioeconomic status and safety of Black Americans. We must fully name what happened— without defending, excusing, or downplaying it—before we can truly move forward. Baton Rouge, La., exemplified this kind of acknowledgement last summer. As the city still grappled with the 2016 police murder of Alton Sterling, Baton Rouge Police Chief Murphy Paul apologized to the city for the killing. He then went significantly further, apologizing for the trauma that policing has inflicted on communities of color for decades. It was a stunning moment. He unflinchingly carried the burden of historical harm caused by his profession and committed to change. Acknowledgement creates space for repairAcknowledgement creates space for repair, the second step in accountability. This is critical in communities of color, where the long history of police violence means that the police badge and uniform are traumatizing. Equal Justice USA works to create a space for healing and build this understanding among police officers through a program in Newark, N.J. For three and a half years, community residents have sat across from police officers and recalled the times they were victims of police violence or other mistreatment. They explain how those experiences changed the way they live and the trauma they feel when a patrol car comes rolling down their block. Police officers learn about the links between slavery, mass incarceration and policing. These painful yet powerful exchanges have helped hundreds of community members and police officers lift up each other’s humanity and fully hear each other’s pain. Participants have described the healing that comes with being able to tell their story of police violence directly to a room of uniformed officers, to be heard and acknowledged, and to share in an examination of oppression. At the end of the process, the group comes together to envision new approaches to healing and safety and a more collaborative, community-centered relationship. This process, of working through the pain together to arrive at a new way forward, is the beginning of repair. Acknowledgement and repair address the past and the present. But these steps are meaningless without behavior change—concrete changes that ensure the harm is not repeated in the future. Behavior change in the case of police violence means more than preventing individual officers from harming again. It also means systemic change—specifically defunding the police and stopping the endless feeding of a system that has inflicted harm and pain on generations of Black people. When we call for police to be defunded, we are not calling for an overnight eradication of law enforcement. We are recognizing that there are more effective ways to address the majority of problems that currently fall to police to handle. We are calling for a balance of the scales between investments in policing and these alternatives, to ensure not just community safety, but community healing and well-being. Cities like Oakland, St. Louis, and Newark have made historic investments in violence prevention in the past few years. (Most recently, Newark voted to reallocate 5 percent of the police budget toward an Office of Violence Prevention.) Among other things, these programs fund highly skilled community outreach workers and violence interventionists, who come from the communities they serve, to mediate and deescalate conflicts and reduce violence without police. These approaches don’t rely on punitive justice. These approaches don’t rely on punitive justice. Instead, they lean on relationships built on trust and an understanding of the social and health-based indicators of violence and harm. Activists and lawmakers are fighting to protect as much violence prevention funding as possible even in the face of an economic disaster. But no investment has been made at the scale necessary to sustain the systemic change needed to actually make Black and Brown people safe in their communities. As a society, this is our collective behavior change to make. We must stop endorsing the militarization of police by objecting to an overall budget that has quadrupled over the last 30 years. We must demand change in the many systems that oppress people of color. We must live anti-racist lives. Acknowledge. Repair. Change. Any one of those steps without the others fails to create accountability that repairs. It fails to recognize that white supremacy is real, that it’s everywhere, and that we must actively and forcefully dismantle it. This is the way we battle racism. This is how we can stop violence. This is the way we flip the page on a history that is shameful and begin a new accounting of what justice really is. That’s justice, re-imagined. Shari Silberstein is executive director of Equal Justice USA. Hip-Hop Has Been Rapping About Reform For Years Through Music, Why Haven’t We Been Listening?8/2/2020 A comprehensive guide to the bigger problem poisoning our nation

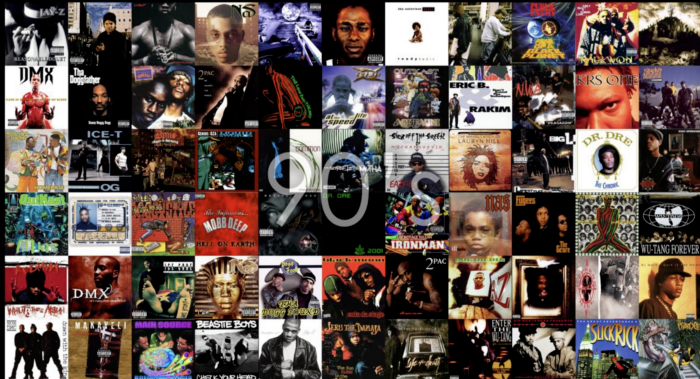

Jessie Dumont The rapper, Ice-T was quoted in 1992 famously saying, “Here we are yelling on a rap record, but no one will listen”, referring to Black on Black crime and police brutality in the 1990's. Almost 28 years later, and the message remains the same and ‘defund the police’ has become a social media hashtag, giving scope to a much bigger issue that doesn’t begin with George Floyd. Broken Record is a podcast created by Rick Rubin that interviews artists across space and time. Mostly, his podcasts center around artist’s processes and how they came to be the famed artists we know and love today. In an episode aired recently, Rubin focused on Tupac and Biggie, and the tensions between rappers and police during the 1990’s. In listening to the episode, also detailed on Slate.com, the message is clear: Something is broken, and we’re just not listening. Hip Hop’s historical feud with police isn’t new, in fact, it blew up in the 1990’s with Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls confrontation on their records, that left an imprint on the climate around law enforcement. The 90’s is often heralded as the Golden Era, and looked on with nostalgia, yet, in the Hip-Hop world? Gangsta Rap was at war with society, police faced backlash from the nation, and music was being dissected for a moment to prove that America needed reform. It is important to trace the hostilities between rappers and law enforcement at this time and the mirage of civility during the 1990’s between the feud that birthed Gangsta Rap. It alludes to a similar climate that exists today, the question still remains: Why haven’t we been listening? Broken Record’s podcast, begins telling the story of a man named Ronald Ray Howard, “He grew up in South Park, a tough neighborhood in Houston. He described it as a war zone. Howard attended nine different elementary schools and was held back three times. When he was 16, he dropped out of high school”(Source: Slate.com). Broken Record introduces Howard’s life in fragments, painting the picture of what would later become a nation-wide story for many reasons, “Howard ended up selling drugs in the town of Port Lavaca, two hours down the Gulf Coast from Houston. That’s where he was headed the night of April 11, 1992, when a Texas Highway Patrol officer pulled him over”(Source: Slate.com). Howard had a lot to worry about that night, when the state trooper pulled him over, not only was he a drug dealer, but he was driving a stolen car, “The patrolman who pulled Howard over was Trooper, his name was Bill Davidson. He’d been on the force for about 20 years. As Davidson approached the car, Howard shot him in the neck with a 9 mm pistol. Davidson died three days later”(Source:Slate.com). Howard was arrested and later, confessed to the crime, yet, it became a national story for many reasons. Howard’s music choice the night of the murder featured: Tupac’s 2Pacalypse Now, solo album, which focused on police brutality. This case is famously argued for hip-hop’s negative influence on its listeners. Tupac’s lyrics were even used in court to build Howard’s defense case in order to persuade the court that he felt compelled to shoot the state trooper from Tupac’s message. As you can imagine, this case built a villainous image around Gangsta rap and sparked a nation-wide debate on hip-hop’s merits. It can be argued that this case changed society’s view of hip-hop forever. It wasn’t too long before Howard’s case that N.W.A had received nation-wide criticism after recording their famous song, “Fuck Tha Police”, and the case of Rodney King, “Los Angeles police officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted on almost all charges, setting off one of the biggest race riots in American history, another song about police brutality became the focus of protests: Ice-T’s “Cop Killer.”(Source: Slate.com). Not foreign to today’s climate, this was a tense time in America’s history that can be correlated with the current climate. In the 90’s, hip-hop music was dubbed a bad influence that brainwashed young people into hating law enforcement. An outcry stemmed from law enforcement warning hip-hop listeners that songs focused on killer cops could cause more violence in the future and a much greater divide. With the birth of Gangsta rap, the feud between rappers and society remained tense. Rappers wanted to be heard, law enforcement wanted to be safe, society wanted justice, especially after Howard’s court case testimony, when he stated: “The music was up as loud as it could go with gunshots and siren noises on it, and my heart was pounding hard,” he told a reporter. “I was so hyped up, I just snapped.”(Source: Slate.com). Howard’s case could be a whole conversation in itself, but to keep the conversation current, Howard’s testimony begs the question that if the concern for safety is boiled down to lyrics in a hip-hop song, why haven’t we been listening to the message and asking for reform much earlier? This moment in history became national news, and may have been the reason hip-hop received criticism from listeners around the country. I believe blaming hip-hop for Howard’s murder was irresponsible. While Howard had a right to build a defense against the crime he committed, hip-hop may have aided his motivation, but it certainly wasn’t the first domino to fall before he shot and killed the state trooper that night. The argument relates today with the move to outlaw violent video games for kids because many parents believe that it breeds learned bad habits, and violent dispositions. As stated in a recent Harvard study on violent video games, Harvard argued that while the topic remains controversial that violent video games are nothing to be worried about, “Although adults tend to view video games as isolating and antisocial, other studies found that most young respondents described the games as fun, exciting, something to counter boredom, and something to do with friends. For many youths, violent content is not the main draw. Boys in particular are motivated to play video games in order to compete and win. Seen in this context, use of violent video games may be similar to the type of rough-housing play that boys engage in as part of normal development. Video games offer one more outlet for the competition for status or to establish a pecking order”(Source: Harvard study; violent video games and young people). To take this study one step further, Harvard argues that violent video games did not have a violent correlation effect on the majority of its users and that those affected had previous mental/emotional distress and trauma that contributed to their violent behavior, “Two psychologists, Dr. Patrick Markey of Villanova University and Dr. Charlotte Markey of Rutgers University, have presented evidence that some children may become more aggressive as a result of watching and playing violent video games, but that most are not affected. After reviewing the research, they concluded that the combination of three personality traits might be most likely to make an individual act and think aggressively after playing a violent video game. The three traits they identified were high neuroticism (prone to anger and depression, highly emotional, and easily upset), disagreeableness (cold, indifferent to other people), and low levels of conscientiousness (prone to acting without thinking, failing to deliver on promises, breaking rules)”(Source: Harvard study; violent video games and young people). To relate this video game study back to hip-hop, it would seem that even the most violent lyrics against police officers wouldn’t effect the majority of its listeners, except if it is listened to through the ears of youth experiencing neroticisim, disagreeableness, and low levels of conscientiousness. Studies have shown that these experiences are influenced by genetics, but also by environmental factors that often make-up high-crime rate urban areas, to use L.A. as an example, “According to publicly available LAPD crime data, there is a trend of rising crime involving the mentally ill in the City of Los Angeles. Crimes involving the mentally ill have increased 338% from 2010 to 2018 (the most recent year for which we have complete data)”(Source: xtown.la-statitics). If hip-hop songs that carry messages about killing law enforcement are being distributed among a population that suffers from the highest rates of mental illness, than, it is easy to conclude that it will most likely have a negative effect on violent crimes and violent actions towards law enforcement, generally speaking. In the case of Tupac, his focus remained on police in his music, especially after Rodney King: “He(Tupac) explained his relentless focus on police violence in some situations that show us having the power and other situations that show more has to happen with the police or with the power structure.”(Source: Slate.com). The power structure is key here. The years of having a broken power structure in our most populated and high-crime cities can lead to disastrous results. While rappers like Biggie and Tupac have voiced their opinions about law enforcement, for years, hip-hop artists have narrated a reality that they’ve been burdened to grow up in, with a goal to escape and never return. The trust that the high-crime neighborhoods will resolve and rebuild on their own is naive, and the argument to defund the police, remains open-ended as we’re left wondering: What about the communities that can’t stand on their own? What about the support that is needed in these cities to create a safer and more reliable future? Rappers such as Mos Def in his songs: Mr. Nigga, and Mathematics, both tell a narrative of these communities: From ‘Mathematics’ by: Mos Def: Like the nationwide projects, prison-industry complex Broken glass wall better keep your alarm set Streets too loud to ever hear freedom sing Say evacuate your sleep, it’s dangerous to dream But you chain cats get they CHA-POW, who dead now Killing fields need blood to graze the cash cow It’s a number game, but shit don’t add up somehow Like I got, sixteen to thirty-two bars to rock it But only 15% of profits, ever see my pockets like To reveal ‘nationwide projects’, and the symbolism that exists through his lyrics, should be a reason to listen, a reason to understand, a reason to change this pertinent issue that stems from nation-wide unrest. Another stanza from his song reads: Full of hard niggas, large niggas, dice tumblers Young teens and prison greens facing life numbers Crack mothers, crack babies and AIDS patients Young bloods can’t spell but they could rock you in PlayStation This new math is whipping motherfuckers ass You wanna know how to rhyme you better learn how to add It’s mathematics The symbolism behind Mos Def’s plea to understand mathematics isn’t to call for police reform or school reform, he serves his audience lines of data that exist in a city he grew up in to exploit the piles of problems stacked against him. He isn’t the only artist to come from grim and violent beginnings, Jay-Z came out with his song 99 problems in 2003 talking about 1994, The year’s ’94 and my trunk is raw In my rearview mirror is the motherfucking law I got two choices y’all, pull over the car or Bounce on the devil, put the pedal to the floor Now I ain’t trying to see no highway chase with Jake Plus I got a few dollars I can fight the case So I, pull over to the side of the road I heard, “Son, do you know why I’m stopping you for?” “Cause I’m young and I’m black and my hat’s real low” Do I look like a mind reader, sir? I don’t know Am I under arrest or should I guess some more? “Well you was doing fifty-five in a fifty-four” (uh huh) “License and registration and step out of the car” “Are you carrying a weapon on you, I know a lot of you are” I ain’t stepping out of shit, all my papers legit “Well do you mind if I look around the car a little bit?” Well my glove compartment is locked, so is the trunk in the back And I know my rights so you goin’ need a warrant for that He continues to rap about an experience with a police officer and how unfairly the man in the song was being treated during this narrative because of the color of his skin. This song received 6 awards, yet, no movement on nation-wide reform. The last hip-hop example I will use also comes from Jay-Z called: Hard-Knock Life which came out in 1998. This song arguably made Jay-Z famous, and is coined the Ghetto Anthem, From standin’ on the corners boppin’ To drivin’ some of the hottest cars New York has ever seen For droppin’ some of the hottest verses rap has ever heard From the dope spot, with the smoke Glock Fleein’ the murder scene, you know me well Using the chorus from the musical Annie, Jay-Z encapsulates life in New York city growing up in the projects, repeating in chorus: It is a hard knock life for us, I’m from the school of the hard knocks, we must not Let outsiders violate our blocks, and my plot Let’s stick up the world and split it fifty/fifty, uh-huh Let’s take the dough and stay real jiggy, uh-huh And sip the Cris’ and get pissy-pissy Flow infinitely like the memory of my nigga Biggie, baby! You know it’s hell when I come through The life and times of Shawn Carter The fact that Jay-Z writes about this experience at all, reveals the problems that have yet to be solved. I could write pages detailing hip-hop lyrics that discuss the exact same message, but I’ll spare you the reading. One thing remains crystal clear: hip-hop has been telling us through song what these communities have needed for a while, we just haven’t been listening, and it doesn’t start with police reform. Shortly after Rodney King, Ice-T stated: “Nineteen ninety two and Los Angeles is ignited by the fires of riots sparking a war of words over justice in America. I feel that the jury in Simi Valley gave the OK to continue to abuse an oppressed and suppress black people in this country”(Source: Slate.com). It sounds a lot like today’s climate, so what about the continuation of abusing and oppressing Black people in this country, was there reform after the Rodney King case? According to Bloomberg City Lab that details police reform in 1992 after the beating of Rodney King, “The commission’s findings did result in the end of the LAPD’s lifetime-term policy for chiefs. That allowed the department to force its notoriously aggressive, divisive leader, Daryl Gates, to resign, and to begin hiring chiefs on five-year terms instead”(Source: Bloomberg City Lab: LAPD REFORMS FOLLOWING Rodney King). While this reform didn’t solve all of the problems stemming from King, it wouldn’t be until 2000 when LAPD reform would really hit the ground running after corruption jaded law enforcement that would grant much-needed change in the LAPD(you can find out more about this from the link below). To give credit, police officers generally join the force to save lives and save the world, the corruption between community and law enforcement can get blurry through the reality that still exists today. While reform for police is a step in the right direction nation wide, I also wonder if we are listening to the rest of hip hop’s repetitive themes such as no support for quality education, no support for mental health, no access to healthy food, no opportunities to make a decent living that turn a lot of community members to take drugs or become drug dealers, that has caused a nation-wide domino effect for impoverished communities. The distrust stems from a life that most impoverished communities are forced to lead — with no opportunities to get out and succeed, most citizens turn to drugs, violence, crime that create a negative feedback loop to the citizens that live there. Hip-hop gives a unique perspective into communities that are left haunted by the fight, flight or flee reality. If we keep failing to support these communities in the places they need dyer help in, we fail to follow through on the reform we promise to uphold. While rappers hold the perspective that a lot of citizens in impoverished communities feel: police are corrupt, and they can’t be free in their own neighborhoods, police often join the force generally, to save the world and are confronted with a society that is held back by crime, poverty and daily illegal activity. While the police generally do their jobs well, the citizens that make-up this community want their neighborhoods to be safe, yet, also, want their freedoms back. In the documentary entitled: Charm City, that depicts the police relationships with inner city Baltimore, the citizens explain that they want police officers around for safety, but when a crime is committed, the police are often blamed for their inaction. It is a system that is broken, a trust that is broken, maybe police reform comes in the form of being more involved in the communities they work in full-time. The majority of Americans are not listening to rapper’s lyrics for a lot of reasons, but those reasons continue to take our nation away from a real problem that plagues an already vulnerable population. We can’t blame the police officers who whole-heartedly join the force to save lives, and we can’t blame the citizens who feel victimized in high-crime areas, both populations are products of their environments, and we need to find a way for those populations to work together towards a common goal. Reform can’t be a one-sided fight, it must address the epicenter in which all of these problems stem from. Hip-hop included. If we can’t listen to the rappers from the 90’s whose main goal was to choose to protest through their music, we fail to acknowledge the war that has poisoned our cities that continue to stay in stagnant state of emergencies for far too long. Sources Used:

a.99 Problems: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6z-xP7E_zMU&list=TLPQMTAwNzIwMjA7q20tXNfWZw&index=1 b. Hard Knock Life: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I97GSE5d0VI 5. Mos Def’s Songs On Youtube: a. Mathematics: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5vw4ajnWGA 6. Charm City Documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcAIGdPJ5yc |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed