Longer training and a better evaluation process for recruits could weed out individuals unsuited to policing, says a retired New York Police Detective. “This training should be akin to an undergraduate degree [specializing in] some form of police science,” said Kirk Burkhalter, now a professor at New York Law School, told ABC News. Burkhalter, who served 20 years with the NYPD before retiring as a detective first grade, said police training “needs to move forward into the 21st century.” Police should undergo at least two years of training and education before they are given a gun and sent out into the streets, added Burkhalter, noting that most existing training for police officers was ineffective. “Pretty much, I would recommend throwing out the book and starting over,” he said. The average police academy class in the U.S. lasts 21 weeks, according to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). As part of an ABC News investigation last year on police de-escalation training, Maria “Maki” Haberfield, a professor of police science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, said, “We have the shortest training in comparison to any democratic country.” She said some Scandinavian countries, including Finland and Sweden, require recruits to go to a four-year police university before they are assigned to departments.

0 Comments

From Harper's BAZAAR

Pride was born out of protest. As the legend goes, it started with the throwing of a brick by a trans woman of color who was exasperated by the status quo. Her name was Marsha P. Johnson, and like all the patrons at the Stonewall Inn in June of 1969, she was fed up with the constant persecution of the LGBTQ+ community by the New York City Police Department. Her act of defiance would spark an uprising that would lead to demonstrations calling for justice and equality for her marginalized community—a rallying cry that 51 one years later is all too familiar. “Pride started out as a revolt against police brutality,” says Cathy Renna, a spokesperson for NYC Pride and Global Pride, among others. “That’s eye-opening for some people. The Stonewall Riots with Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera throwing bricks is the Hollywood version. The truth is that our community at that time was constantly harassed, beaten, and arrested by the police. It’s very much the way we see Black Americans today. Tying those things together and helping people understand that our shared history is very similar has really helped contribute to what we’re seeing in the streets, which is a hugely diverse group of people.” The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Rayshard Brooks—much like that fateful day in 1969—prompted the public to unite and demand an end to systemic racism. The Black Lives Matter movement has been reignited, but unlike its first iteration in 2013, the whole world has now taken notice of the racial prejudice that runs through all institutions. Moreover, the movement began to shed light on Black trans people and the alarming amounts of violence inflicted on their community—statistics that have only now received the public attention they deserve. “We have been trying to get the media to cover the murder of Black trans women for years,” says Sarah Kate Ellis, president and CEO of GLAAD. “In fact, we even wrote a media guide several years ago to bring this to the forefront, to get attention. This has been an epidemic in our community.” The undermining of trans people reached a fever pitch with the Trump administration’s latest attempt to repeal health care protections implemented by the Affordable Care Act—and was compounded by the recent deaths of Riah Milton, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, Tony McDade, and Nina Pop. All this incited additional gatherings in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, with protesters collectively calling for the Black Lives Matter movement to account for all Black lives and not just those of conforming genders. “There are issues related to racism in the LGBTQ community, and homophobia and transphobia that exist in communities of color,” Renna explains. “It is important for those of us who want to move forward, make progress, educate, and unite people to elevate that, to bring it out. I think that it’s incredibly important that we all get out in the streets for all of those affected. I have a friend in Washington who is a trans man and is afraid to go to the protests, because he might be targeted—not just by the police, but other folks who might be in the crowd who are anti-trans.” Still, LGBTQ+ organizations are remaining unified in their campaign against all forms of bias. As Ellis expounds, the community is composed of individuals of all creeds, colors, and races—people who are indigenous and with disabilities. “We encompass everyone, and we must fight for all those that are marginalized,” she says. “Until everyone in this world has full protections, full acceptance, we are always fighting.” This is why celebrating Pride is crucial. In memory of the Stonewall Uprising, June has been designated the month when the people of the LGBTQ+ community take to the streets to celebrate. For more than five decades, people from all walks of life have marched in parades filled with colorful floats, banded together behind the rainbow flag and its message of diversity, and waved banners and worn outfits that pronounce their identities proudly. It is a collective demand for acceptance; a time to remember the struggles of the past, honor the achievements made over half a century, and highlight issues that still need to be addressed. In essence, Pride is as much a party as it is a political statement. “It is like a Rorschach test,” says Renna. “Pride is different for everyone, but it is absolutely a form of protest. It is a platform, quite frankly, to make sure people understand what our issues are and the work we have to do. It is a place where anyone can celebrate who they are, surrounded by their tribe. It is about visibility, which is one of the most powerful things we have to show our political clout, to show the world that we are very deserving of equality.” Topics regarding same-sex marriage, anti-crime, and, more recently, job protection have been central themes at past Prides in the United States. And though these hard-fought rights have since been ratified by the Supreme Court, they only scratch the surface. “We need the Equality Act that has been sitting on the desk of [Senate Majority Leader] Mitch McConnell for almost a year if not longer,” says Ellis. “Right now, we’re piecemealing protection together. We need full, comprehensive protection as a community. This piece of legislation needs to be passed.” This year, however, the most prevalent issue is the Black Lives Matter movement, and many LGBTQ+ organizations are making sure that the message of racial inequality gets communicated loud and clear—even amid a global pandemic. “This moment in time, in the environment that we’re in right now, the culture that we’re living in right now, it’s critical that we use the platform of Pride to lift the voices of our LGBTQ brothers and sisters who are people of color,” says Ellis. Indeed, the coronavirus outbreak has affected all public-facing events. Several weeks ago, government officials enacted stay-at-home orders and closed all nonessential businesses in an effort to flatten the curve of COVID-19; though recently, restrictions have been lifted state by state, with virus cases still on the rise in some areas but subsiding in others. Nevertheless, Pride organizers are not taking any chances. “The health and safety of the community is always going to be the first concern,” says Renna, who traditionally facilitates two of the most visible events during Pride Month. “This is why keeping them virtual is really important.” For NYC Pride, in particular, it wasn’t a question of if organizers were going to host events this year, but how. Their solution was to transfer the myriad in-person events to an online setting and create programming that could both educate and entertain. Already, the organization has partnered with GLAAD for Black Queer Town Hall, a virtual discussion led by drag stars Peppermint, Bob the Drag Queen, and Jaida Essence Hall. Toward the end of the month, it has arranged a virtual rally with trans activists Ashlee Marie Preston and Brian Michael Smith, a human rights conference, and a special broadcast that will spotlight Janelle Monáe, Deborah Cox, Billy Porter, and Dan Levy. In addition, Procter & Gamble and iHeartMedia created Can’t Cancel Pride, the Los Angeles LGBT Center sponsored Trans Pride, there’s the Frameline44 Pride Showcase, and cities from Chicago to Seattle are hosting their own virtual Pride parades. On the international front, Global Pride has corralled more than 40 personalities from the worlds of politics and entertainment—including Vice President Joe Biden, Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, singer-songwriter Adam Lambert, and actress Laverne Cox—for a 24-hour event that focuses on the Black Lives Matter movement. With the spirit of protest pervading 2020, there’s no stopping the LGBTQ+ community from celebrating Pride and promoting equality. COVID-19 may have changed the format—temporarily putting a suspension on parades and limiting gatherings to those hosted by close friends and family—but many plan on keeping the party going while also practicing social distancing. “Pride is the ultimate opportunity for expressing who you are,” says Ellis, and that doesn’t necessarily require taking to the streets. So for Pride 2020, BAZAAR.com is asking members of the LGBTQ+ community to demonstrate just that. From fashion designers and filmmakers to singers and drag superstars to artists and social media influencers, vanguards of disparate industries relay their most memorable Pride event and express why dressing up for the occasion—even while at home—is important. Some re-create their old looks, while others come up with new ensembles that best represent their feelings this year. Either way, all let their true colors shine through. Kim Petras What was your most memorable Pride event? I went to my first Pride in Cologne, Germany, when I was 12 or 13. I went with my friends and felt less alone, because it created a space for us to celebrate our individuality. That’s what Pride really means to me: celebrating your differences. Another memorable Pride was when I headlined World Pride in NYC last year. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I’ll be taking part in online events and doing what I can to raise awareness of LGBTQ issues using my platform. Pride is more than just a parade. It’s also a place to reflect on those that came before us and realize how far we still have to go, even with the recent Supreme Court law prohibiting workplace discrimination against LGBTQ people—especially for queer people of color. Violence against the Black trans community is still so prevalent, so it’s more important than ever to show up this year and make sure all celebrations in whatever form they take are intersectional. Who gives you Pride, and why? My fans, for sure. They’ve given me so much. They’ve accepted me for who I am, support me, and I feel honored that they have given me a platform I can use to show people that you can do anything and be anything you want to be, no matter your gender or sexuality. I’ll forever be really grateful for that. I love that I’m in a position where I get to inspire young LGBTQ people. I definitely needed role models growing up, and I think if there had been a transgender pop star, I would have felt more optimistic and excited about my own future. I’m blessed that I’m in a position where some people see that in me. How do you express Pride through fashion? Fashion is how I show my individuality and personality. It’s how I express myself outside of my music, and it’s such an important part of who I am. It’s something I’ve always been obsessed with. For me, Pride is all about celebrating your differences. Fashion and style help those differences shine a little brighter. Jonathan Simkhai What was your most memorable Pride event? Our wedding anniversary is this month and definitely my most memorable Pride event. We chose to get married during Pride Month, because it was incredibly important for us to stand that day with all the people we love in solidarity with the entire LGBTQ community. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? My twins just turned two and are really into Rihanna, so we’ll definitely have a dance party with music from all LGBTQ pioneers. Who gives you Pride, and why? Pride is such an important celebration to simply pay homage to the forgotten Black and Brown trans women who threw those first bricks; to the women and men who watched our community being wiped out, yet still will fight for equal rights up until the recent Supreme Court decision. It was a landmark decision that will impact all future LGBTQ generations, a decision that will allow us the chance to witness its results positively ripple through so many aspects of LGBTQ life. How do you express Pride through fashion? Fashion had always been a home for me as a young, queer kid. Seeing fashion and its celebration of queerness always made me feel accepted, and it still has that effect on kids all over the world. Shangela What was your most memorable Pride event? My most memorable Pride event was NYC WorldPride 2019. I will never forget the feeling of riding in the float with Macy’s, in one of the biggest parades, surrounded by my friends and millions of people celebrating love and equality. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I believe that this Pride may be one of the most important that I have ever experienced. Although we are celebrating Pride in a way that many of us have never done before, I hope this Pride month reignites people’s understanding of why Pride even exists. Pride is a result of protests of inequality and injustice, and can only truly be celebrated when we all are being active in raising our voices for equality. Who gives you Pride, and why? The new drag children that I have gained through filming the show We’re Here have truly given me a greater sense of pride than ever before. I see a reflection of myself in them and how my confidence and unapologetic queerness have truly inspired them to live as out loud and proud as they can be. How do you express Pride through fashion? A lot of times, I use fashion to express my identity outside the confinement of gender constructs. I have the greatest love for myself when I feel good about what I am wearing, whether it is masculine or feminine. Pride to me means freedom and love of one’s self-expression, and what better way to express myself than through fashion? Phoebe Dahl What was your most memorable Pride event? My favorite Pride was actually a very mellow one. My closest friends and I went to the Dyke Day event in Elysian Park in L.A., and it was basically a giant picnic with every lesbian in L.A. The only downfall is running into every ex-girlfriend you’ve ever had. Ha! How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I’ll be having a small get-together with my closest friends who I’ve celebrated Pride with for the past couple of years. It’s such a special time to be able to come together to celebrate everyone’s uniqueness. Of course, I’ll miss the actual parade, but am enjoying the intimate nature of the world’s climate and think it’s important to find support in small numbers to uplift each other through celebration and community. Who gives you Pride, and why? My sister Chloe is a part of the LGBTQ community, and she has always been my support and inspiration. As well as being my sister, she’s an amazing ally and someone who constantly offers support and advice. I feel so lucky to have such an amazing group of friends who are all so diverse and wild, and they give me so much joy and endless laughter. I also love the organization It Gets Better. I think it’s an amazing source of personal stories within the LGBTQ community. It’s so important to know that you’re never alone in what you’re experiencing. How do you express pride through fashion? I don’t really have a specific way of dressing—I just try to dress however I feel that day. Sometimes I’m dressed like a total tomboy, and sometimes I dress super femme. But it’s nice to have the freedom to express myself however that may be and not be confined to a box. Prabal Gurung What was your most memorable Pride event? Last year was a particularly memorable Pride Month, especially being the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. We hosted an incredible dinner at the Wythe Hotel, and it was so special for me to have the opportunity to contribute to the celebration of the LGBTQI+ community, and to honor this month of love and resistance in my own small way. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I have been thinking a lot about how we can celebrate Pride Month by honoring our Black queer and trans family who fought for the civil liberties we as a community now get to enjoy. I kicked off Pride this year by participating in the Brooklyn Liberation march, an action for Black trans lives. It was such a moving and emotional day. I am honored and so grateful to have witnessed this momentous act of unity and love. Who gives you Pride, and why? I am so inspired by all the incredible activists who are doing the work on the ground and consistently showing up for the community: Indya Moore, Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Janet Mock, Kimberly Drew, Phillip Picardi, Raquel Willis, Ashlee Marie Preston, Ceyenne Doroshow, and so many more. Their constant dedication to the fight against injustices for Black lives, people of color, and the LGBTQI+ community is an example in fortitude to us all. How do you express Pride through fashion? My brand’s ethos, “Stronger in Colour,” is a rallying cry for a vibrant world full of diverse beauty and culture. My use of prints and colors in my designs, and my wardrobe, is a metaphor for the world I wish to see around me: representative, diverse, and inclusive. Jameela Jamil What was your most memorable Pride event? My most memorable was last year when my company, I Weigh, set up our own little station at Pride in L.A., just a space for dancing and fun and topping your self-confidence all the way up to your eyeballs. So many people turned up and it made me feel very proud to know our work resonates with the LGBTQ+ community so much. It was beautiful. Pride has an atmosphere of such joy, such love, and such acceptance; people of all ages, all races, all shapes and sizes celebrating each other. I felt so safe and so joyous. I wish the whole world was like a Pride event. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I am celebrating it by binge-watching Legendary, the new show I made with ballroom icons Leiomy Maldonado and Dashaun Wesley, as well as my stylist Law Roach and the inimitable Meg Thee Stallion. It celebrates queer joy, love and talent. I will also be checking in with all my friends from within this community. Because while it’s a huge celebration, it also comes with a lot of backlash, and extra support is needed. Who gives you Pride and why? Munroe Bergdorf gives me pride. I wish I had known someone like her when I was a kid. She is such a smart and brave activist who takes on so much, to stand for Black trans women everywhere. She is my biggest inspiration. How do you express Pride through fashion? Pride taught me to be extra. To be unapologetic. To make the most of what I wear and to never try to blend in. To always stand out proud. I owe all my love of glitter, sequins, feathers and tuxedos to Pride. This year, I’m wearing a black sequin suit made by Rick Owens, a gender fluidity fashion icon. Shantell Martin What was your most memorable Pride event? Pride in London in 2004. I was back in London visiting from Japan, and I met up with friends. We went to a Tottenham Hotspur football game—my first-ever football game, actually—and a friend bought me a jersey. So we all were decked out in football gear in this crazy environment—a stadium full of thousands of men shouting and chanting and singing, all that macho-man energy. It was a very straight, yet a kind of incredible traditional English experience. After the game, we went down to Soho for Pride. You could not have asked for a more beautiful day in London. Everyone was stunning, dressed in the most amazing looks. People were crying, there was so much love and real pride flowing down the street, like a river. So you can imagine how beautiful this was to experience—two completely different worlds, all in one day. It was perfect. Unforgettable. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? My partner and I will have quite a few Zoom sessions and FaceTime calls with all our LGBTQ+ friends, and then we’ll watch a documentary or LGBTQ+ film. Who gives you Pride, and why? Debbie Millman and Roxane Gay, because they’re both amazing and contribute greatly to the world in so many different and creative ways. Also, I greatly admire the way they’ve shared their love with each other with the world. It’s so beautiful and brave. Lesbians Who Tech, because they’re innovative; they push the envelope in an industry that really needs more voices from women and the LGBTQ+ community. And Planned Parenthood, because through thick and thin, they’re out there supporting everyone in ways that are essential to people’s lives and health. How do you express Pride through fashion? By being completely myself. I don’t dress for anyone else but me. But for Pride, I do indulge in wearing a little bit more color than normal. Bretman Rock What was your most memorable Pride event? The most prideful I ever felt was during Spirit Week in high school one year. During the assembly, I was the star and I dressed up like a female pop icon. I guess that was, like, the first time anyone in my school—or any assembly, really—dressed up as the opposite gender. That was actually the first day I wore makeup to school. I think it was so cool just to see everyone cheer for me. I felt so prideful. And ever since that day, I had the confidence to start wearing makeup to school. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? Funny you ask that. I can’t really tell you the PG version of it. I guess I could say that my assistant, my boyfriend, and my two best friends—we’re all gay—are just going to have our own little house party. Pride this year will be just the five of us being gay and having a little kiki. Who gives you Pride, and why? Oh, bitch, The Trevor Project. I just love watching The Trevor Project gala every year. I feel like all of my favorite queer and trans icons go there. I love to see what everyone is wearing. And I love working with them and feel it’s an honor to be associated with them. They make me feel proud to be gay and proud that someone has our back. How do you express Pride through fashion? Well, first, let’s describe what Pride means to me. Pride to me means being your 100 percent complete self without fear of any judgment. Pride to me means doing things that make you happy. And so I feel as though, when it comes to my fashion, I try to exude pridefulness by wearing whatever the fuck I want. Men’s clothes or women’s clothes. I just make sure that my fashion is always 100 percent me. Ruth Koleva What was your most memorable Pride event? I will never forget that moment when I was invited to sing at Sofia Pride for the first time seven or eight years ago. Bulgaria is still highly criticized for not accepting gay marriages or unions. LGBTQ+ people are targets of social, institutional, and work discrimination and experience violence quite often. I was the first public figure and musician to stand up and show support for Pride. I remember receiving death threats online and how scared I was when I went to the stage to perform. There were more police officers than the actual audience. Nevertheless, the love and courage these people had back then, and the passion for justice and equality made me realize that Pride is a life mission for me. I've been performing at Pride [events] around the world for the last seven years. And this year, I dedicated the first single of my new album to the LGBTQ+ community, which is basically my family now. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I will be singing songs online the whole month and planning to do some interstellar collaborations with amazing LGBTQ+ artists around the globe on my Instagram. Who gives you Pride, and why? I have enormous respect and love for all the organizations around the world fighting for equal rights for LGBTQ+ people. I am personally involved as an adviser in an organization called Single Step, which gives support for LGBTQ+ youth, and I have been working extensively with Sofia Pride since 2017. How do you express Pride through fashion? Pride is love and self-expression. Honestly, during Pride, I've seen the most iconic fashion there is. Even walking the streets of New York, you can be blown up by color inspiration. Brad Mondo What was your most memorable Pride event? My first Pride was when I was 18 in Providence, Rhode Island. It was a wild day of me sneaking into 21-plus events. My first pride was one of the best days of my life. I felt so welcome and accepted. It was such an amazing feeling. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I’ll be celebrating Pride by remembering who are the key players in getting us to the point that we’re at today. People like Marsha P. Johnson, who was a black trans woman and was one of the first people to push back against police at Stonewall. Pride is bigger than ever this year in a lot of ways, and we need to remember how important Black LGBTQIA+ people are in bringing this movement forward. Who gives you Pride, and why? Artists like Kim Petras, Troye Sivan, Sam Smith, Frank Ocean, and Lady Gaga give me pride. They make me feel that being gay is not only accepted but encouraged and exciting. People like Lady Gaga made the young, teen, gay Brad feel the most pride ever, when I could rock out to songs like “Bad Romance” on repeat in my room. How do you express Pride through fashion? I like to push boundaries with my fashion choices. Being bold with the colors and cuts of the pieces I wear has always been a way of me expressing my pride. Fashion is my way of telling the whole world how proud I am of being gay. Sequins, sparkles, bright colors, you’ll see me in all of it, hunny. Peppermint What was your most memorable Pride event? Pride 2006 with Alec Mapa. The theme was Sleep Over. We were piled onto a bed, and it was pouring rain during the parade. We were soaked and loving it. How are you celebrating Pride at home this year? I’ll be watching the documentary Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen, learning about the history of trans inclusion—and exclusion—in Hollywood. Who gives you Pride, and why? The Okra Project is a great source of Pride for me this year. They focus on solving food insecurity for LGBTQ of color. How do you express Pride through fashion? My favorite way to express Pride though fashion is makeup. It can be subtle or dramatic—and anyone can wear it. This is not new.

Let’s not pretend to be shocked now. Seven years ago, I was playing for Milan in a friendly game when a group of fans made monkey noises every time one of our black players touched the ball. After 26 minutes I told the referee, “If they do that again, I’m gonna stop playing.” He said, “No, don’t worry, just continue.” Then, as I was trying to dribble past a player, I heard them again. I grabbed the ball, booted it toward the stands and began to walk off the pitch. It wasn’t the first time I had been racially abused. But this time I just exploded. When the referee tried to get me to play on, I said, “Shut the fuck up.” (Sorry for my language.) I told him, “You had the power to do something. You did nothing.” When a rival player wanted me to stay on, I said, “You shut the fuck up as well. What did you do about it? Do you like what they’re doing?” As I walked towards the tunnel, our captain, Massimo Ambrosini, asked me, “Are you sure about what you’re doing?” I said, “One hundred percent sure.” Let me take a moment to explain why I did what I did. Some people have said that I’d never have done it in a Champions League game, where our team might be deducted points or whatever. But I couldn’t control it. I had bottled up so much anger and pain, and that day the lid just blew off. I know it’s difficult for white people to understand, but that’s because they have never been hated because their skin is a different colour. Still, let me try to explain. When I was nine years old, I went to play in a tournament in East Germany. I grew up in a neighbourhood in Berlin that was poor, and that was also home to people who were from every corner of the world: Russia, China, Egypt, Turkey, everywhere. When we fought each other, it was because we disliked each other in that moment, not because of discrimination. I never experienced racism there. But at the tournament in East Germany, I heard parents shouting at me from the sidelines. “Tackle the n*****.” “Don’t let the n***** play.” I was so … confused. I had only heard that word like maybe in a song or a movie or something, but I knew it was something against my colour. I felt so alone. I felt as if I was in a place where I was not supposed to be — but this was only a six-hour drive from Berlin. How could they love me in one part of the country and hate me in another just because I’m a different colour? As a kid, you don’t understand that. I had never spoken to anyone about how to deal with a situation like that. So on the bus back to Berlin, I burst into tears. My teammates started crying, too. None of us understood what had happened. I never told my mum about it. I just ignored it and kept going. I thought, It’ll go away. But it didn’t. And every time I played in East Germany, it got heavier. “For every goal you score, we’re gonna give you a banana.” “I’m gonna put you in a box and send you back to your country, fucking n*****.” It hurt so badly. When I was 14, I asked my teacher, “Do you see me differently from the other kids?” He said, “No. Why?” I said, “So why do they see me differently in the east? This is my country. I’m German. My mum’s German. So why do they want to send me away?” He explained that there are just some people in this world who are stupid. But I began to cry. I still couldn’t understand it. And soon the confusion turned into suspicion. You begin to think that people don’t like you, even though you don’t know them. Every mixed-race guy in Germany has this. It’s like, Why are you looking at me? You don’t like me? You want trouble? Let’s go. I became aggressive. Disturbed. I got red cards all the time. I was a hothead. But you know what the worst part was? No one ever stood up for me. They knew what was happening to me. They heard the racism — and they just accepted it. The parents stayed quiet. The referee? Nothing. The coach? “Just ignore it.” So I did. I stored my anger inside. I became numb to it. But when I heard those monkey noises in January 2013, all the pain, all the sadness — it all came out. I snapped. I didn’t care if I got in trouble. I had worked all my life to play for one of the biggest teams in the world, and now I was going to be treated like I was when I was a kid?? I just went, No. I’m done with this. I’m going to fight these guys. As I walked off, a lot of people stood up and applauded me. And then — and this is the key — my teammates walked off with me. Not just the black ones. All of them. I still get goose bumps talking about that. When I got to the dressing room, I took off my clothes just to show everyone that I was not going back out there. The referee came in and asked us, “Do you want to continue playing?” And at that moment Ambrosini stood up and said, “If Prince doesn’t play, no one plays.” Chapeau. That episode became huge news around the world. Within a day they knew about it in Ghana, in China, in Brazil. The press was all over it. Big players like Cristiano Ronaldo and Rio Ferdinand were supporting me and talking about what a disgrace the supporters were. My phone blew up with calls and messages. Overnight I became an ambassador for the fight against racism. None of that happened because a black person walked off the pitch. No. It happened because white people walked off with him. That was the message that changed the world. At least it did for a little while. At the time I thought that this could be the change we needed. I really did. FIFA invited me to meet Joseph Blatter. He asked me, “What can we do about it?” Then in March, FIFA set up an anti-discrimination task force and invited me to join it. It seemed perfect. I would train and play games and stuff, but I would also give these people input, and then they would introduce campaigns, rules and punishments. I also gave Blatter a suggestion: To put cameras and microphones in the stadiums. That way, if somebody chanted something racist — BANG, out. I told Blatter, “Listen, try this. If it works, you’re a hero. If it doesn’t, O.K., you tried.” After that, the task force had meetings. We talked and exchanged some emails. But nothing really happened. Whenever I was playing people began to target me, hoping that I’d go nuts and walk off again. I’d go to the referee and tell him to do something, they would make an announcement over the stadium speakers, and then after a minute of quiet, the fans would just keep going. A month later, the media stopped talking about it. And then in September 2016, I received an email from FIFA. I will never forget what it said. It basically read, “The task force has fulfilled its mission. We did our job.” They closed it down. I called my agent and said, “This is a joke.” What did they achieve? What did they do? They fined teams 30,000 euros? And then the fans could return to the stadium the next day?? And their kids are going to see that and take that as an example??? What is 30,000 euros to a club? Nothing. That’s the punishment? That’s the consequence? I honestly believe FIFA set up that task force just to make it seem as if they were doing something. I’m not even scared to say it. It’s a fact. I don’t know why they’re not doing more. You’d have to ask them. I can just assume that it’s more important to them to have VAR telling us whether the ball was over the line than to get rid of racism. They have so much money, they invest so much in cameras, goal-line technology, everything. But fighting racism? Nah. That doesn’t get more people into the stadium. That doesn’t bring in the big bucks. That’s what I think. And remember, FIFA set up that task force in 2013. That’s SEVEN years ago. And now we’re still here talking about the exact same problems…. Nothing has changed. Nothing. If anything, racism has gotten worse. You know, we always look to the U.S. when we talk about racism, but it happens in Europe, too. Maybe we don’t die, maybe we’re not killed, but they push us down all the time. All the time. It’s just more hidden. When I’m out on the street, I can feel it in the way people behave. They look at you. They change sidewalks. When I’m in my car, I can see what they’re thinking. How can a black guy with tattoos drive a car like that? He must be a drug dealer or a rapper. Or maybe an athlete. Why is it like that? Because racism is so deeply embedded in society. It’s systemic. And the white people who are on the top of this system, they don’t want it to change. Why would they? Things are going great for them, just like they did 300 years ago. Let me give you another example. In August last year Clemens Tönnies, the chairman of Schalke, one of my former clubs, made an unbelievably racist comment. He said that instead of increasing taxes to protect the environment, the German government should install power stations in Africa, so that “the Africans would stop cutting down trees and produce babies when it is dark.” I was shocked. This guy had black players in his team. I was like, Kick him out! The press said, “Yeah, it was wrong.” The club said, “We are against racism.” But you know what they did? They suspended him for three months. Three months. A nice, long holiday. And then he was back at work. This is the system. And it goes so deep that this kind of stuff has become normalised. But the thing is, we are way more people than those who run the system. We have more power. We have a louder voice. They cannot win against the whole world. It’s impossible. That is, if we stand together. If we all speak up. If we decide to act. The other day I saw a video on Instagram in which a college teacher tells a room full of people, “Stand up if you want to be treated like a black person.” Nobody stands up. That, in a nutshell, is racial injustice. It’s people who know what is happening to us, but who do nothing. Whenever I have heard racist chanting, there have been people who, although they were standing close to it, acted as if nothing was happening. As if to say, Oh, it’s not that bad. Well, in case you haven’t watched the news lately: It is that bad. I’m writing this article for many reasons. I’m angry. I cried when I watched the George Floyd video. I had to watch it five times to fully realise what had happened. If you listen to his voice, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,” and, “Please, Mama”… it’s just so painful. Who do you talk to when you’re close to death? God, because you’re hoping to see him and asking for forgiveness. And Mama. He knew he was going to die in that moment. He knew. It still makes me emotional … because you see yourself in him, you know? And I look at my kid, and I think, How can I explain that to my son? How can I explain that a man died because of the colour of his skin? I saw Floyd’s daughter say, “Daddy changed the world.” I love that message. And I believe she might be right. These protests can become a turning point. More people are starting to understand where black people are coming from. They understand that we’re not here to go to war. No. We just want what is promised to everyone else. I loved it the other day when my older brother sent me pictures from Berlin, where everyone was in the streets putting up their fists in support — Mexicans, Arabs, Turks, black people, white people. The same thing is happening in Paris, Milan, London, Stockholm, Amsterdam, NYC, everywhere. There is just one thing that worries me. Right now we seem to understand. We seem to be learning. But I worry that, in a few weeks, the world will forget. I worry that in July or August, the protests will have died down, the media will have stopped talking about them and the whole issue will fade away. Just like it did in 2013. So that is also why I’m writing this article. We have to make sure that this doesn’t die out. And to do that, we need white people to stand with us. Right now the Black Lives Matter movement has a lot of power, but we cannot do it alone. It is white people who are controlling this world. It is white people who can undo systemic racism. But if the white hand keeps pushing us down, we have no chance. So tell us that you’re with us. Tell us that you feel for George Floyd. Tell us that you feel for the black community. Because that’s how we’ll know that the world is actually on our side. That the vast majority of people want this to change. That’s the key. I want to do my part. I’m gonna start with Berlin, and then I’ll take Germany, Europe, the U.S., and hopefully the world. I’m not scared. If my sponsors or my club kick me out tomorrow because of something I said in defence of equal rights, I truly don’t care. I only want to work with people who are woke. I thought about a George Floyd Day to celebrate the black community and black excellence. I’d like to see a concert in Berlin where everyone is invited, but where the focus is on Black Lives Matter. I’m writing a song about it. People have told me, “Bring it out now.” No. We’re going to bring it out in July, so people don’t forget. If I have to spend my own money, I will. I won’t give up, that’s for sure. But I need your help and support; I’m a footballer with ideas, raising his voice for a good cause. I know that there’s going to be another protest in Berlin next month, and I know many countries are keeping up the pressure with their protests. That gives me hope. At least we know that this won’t last for just another week. It has to last longer than that. Way longer. And for that to happen, we need everyone. And we especially need the following people: The Players There are athletes who are doing this properly: Colin Kaepernick, LeBron James and Megan Rapinoe. These are some of the big ones — there are many more who are doing amazing work. But footballers, clubs and federations? In Europe? Other than Marcus Rashford, who has shown the world what is possible when we use our platforms, I don’t see much being done. When Australia was burning earlier this year, everyone was talking and posting about it and donating crazy money. It was beautiful to see. But now? I don’t see anything. I don’t see no interviews, no players talking. Where are you guys? Where are the very biggest players in the world? There are too many players who are scared, or who don’t have the character to talk. And I feel a responsibility to call on their support to join me and the movement. I can only reach eight million people on my social media, but I’m going to use every single one of them every day. You guys have tens of millions. This is the moment to show your face — and not on a billboard for a perfume or an advert for new boots — but to raise awareness and create real change for the Black Lives Matter movement. We need every player to listen, learn, and take action. Blackout Tuesday? That’s too easy. A T-shirt that says, NO RACISM? O.K. But do more: Learn about black history and the struggles your black idols have endured. Make a video. Say, “I stand with every black person on this earth. You’re all my brothers and sisters. I love you all.” Donate to programs fighting to end systemic racism and abuse of power. Tell your brands and sponsors to do more than just post slogans. And if they don’t? Adieu. That’s what I want. And don’t wait till next week. Do it now. Do it now, and then do it next week and the week after. You are the biggest players in the world. If you don’t have the chance, who has the chance? If you don’t have the reach, who has the reach? The Media Journalists and editors, don’t let this moment slip away. Don’t forget it after a week. I get that people want to talk about LeBron’s shooting ability or Michael Jordan’s Flu Game. I get that. But there is more important stuff going on right now, and you have a responsibility to cover it. So talk about racism. Keep the stories on the front pages and at the top of your sites. Let people read and understand. And keep it coming, this year and the next year and the next. We need it. Interview people. There are so many like me who have stories and feelings about racism. Maybe they can give us some new perspectives on it. Maybe their voices can give those who are staying silent the courage to speak up. White People I want to say this again: White brothers and sisters, you are the ones who can change this world. We need you now. Especially now. You need to help us. Because you don’t want to be treated like us. Some people are like, “Yeah, but all lives matter.” Of course all lives matter. But the black community is burning. So if my house is burning and your house is not burning, which house is the most important right now? Right. So help me put out the fire. And then we can both live in nice houses. Everyone can do something, even if they think they can’t. One white friend of mine actually told me that he didn’t want it to seem like he was jumping on the train. And I said, “But that’s the train you want to jump on! That’s the train that’s gonna change the world!” So I’m asking you: Jump on the train. Some people are always going to hate. Some people are always going to criticize you. But don’t be scared. Don’t be silent. We will stand with you. We just want to know that you stand with us. A federal lawsuit filed against the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry accuses the state of practicing slavery through its use of private prisons.

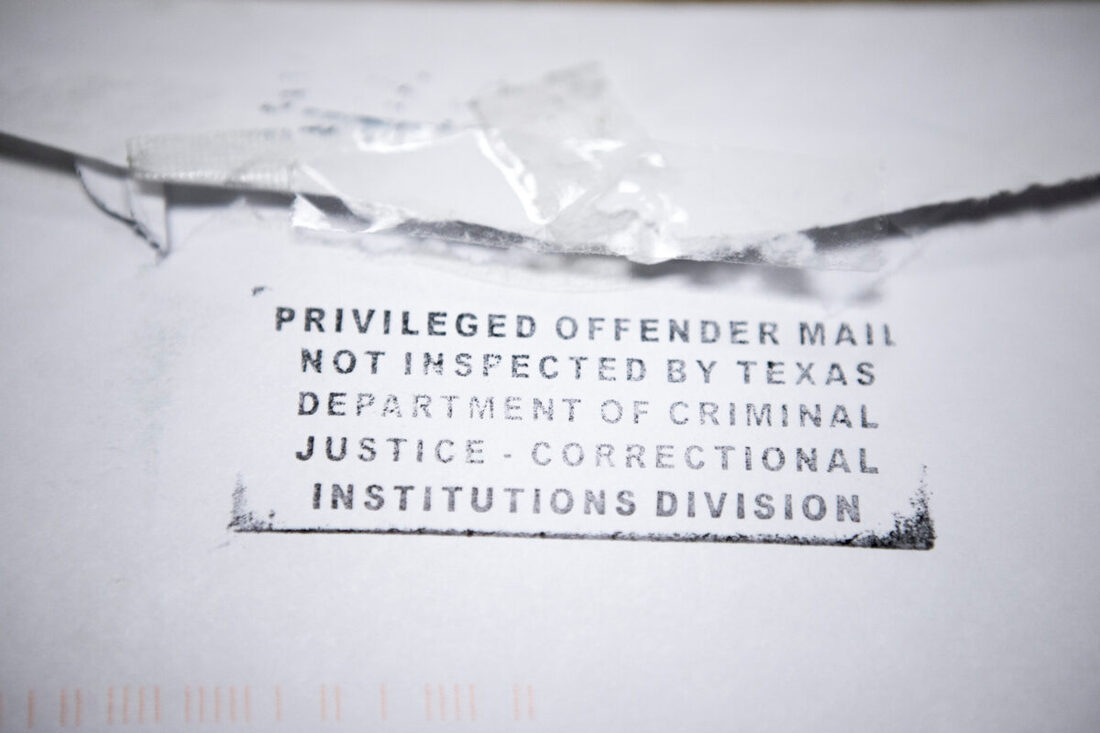

Five inmates and the NAACP filed the class-action lawsuit this week in U.S. District Court in Arizona. The lawsuit claims Arizona is practicing slavery by sending inmates to private prisons to "generate revenues and profits for the monetary benefit of corporate owners, shareholders and executive management." The state corrections department contracts with six private facilities. As of Tuesday, 7,740 inmates were incarcerated in private facilities out of the overall state prison population of 40,547. Patrick Ptak, a spokesman for Gov. Doug Ducey, said he could not comment on pending litigation. The governor's focus when it comes to Arizona correctional programs "has been on providing second chances," Ptak said. "We want to see those serving their time have every opportunity to reenter society successfully," Ptak said. "We've implemented many programs that provide job training, drug rehabilitation, counseling and more." The three private prison companies operating in the state also pushed back. Issa Arnita, a spokesman for Management and Training Corporation, told The Republic that the lawsuits claims are "blatantly false and slanderous." He said the company has provided states and the federal government performance-based correctional services for decades. "Our focus on effective rehabilitation programs has helped people overcome addiction, learn problem-solving skills, participate in faith-based programs, and obtain their GED," he said. "So, it’s just the opposite — we’ve seen thousands of men and women take advantage of evidence-based programs we provide to make lasting changes in their lives." The attorneys said in a statement their goal is to place the issue of private incarceration before the U.S. Supreme Court. One of the attorneys for the inmates and the NAACP is Thomas Zlaket, former chief justice of the Arizona Supreme Court. John Dacey, executive director of Abolish Private Prisons, said they hope the nation's highest court will declare private prisons unconstitutional before a majority of states rely on them. The lawsuit was filed the same week as Juneteenth, which celebrates the Emancipation Proclamation. On June 19, 1865, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger informed people in Galveston, Texas, that enslaved African Americans were free, two years after the signing of the proclamation. Attorneys told The Arizona Republic it was a coincidence that the lawsuit was filed this week, on Monday. For-profit model called into question Attorneys for the inmates and the NAACP claim the state is violating constitutional rights by enforcing slavery and cruel and unusual punishment, and depriving them of due process. The Arizona State Conference for the NAACP's mission, in part, is to reduce mass incarceration and the criminal justice system's disproportionate impact on people of color . A May report by the Department of Corrections' reflected the NAACP's concerns. People of color made up more than 58% of the overall Arizona prison population. However, the five named plaintiffs in this week's lawsuit are white. “We are proud to be plaintiffs and represent the thousands of NAACP members here and across the country — past, present, and future — who fought for freedom and who will live to see its fruits,” Charles Fanniel, executive director of the Arizona state conference of the NAACP, said in a statement. “Using a person’s incarceration to generate corporate profits is a form of slavery," Dacey said in a statement. “A profit-motivated criminal justice system also conflicts with individual rights that are protected by the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Constitution.” He said the business model encourages incarceration of more people for longer terms. David Shinn, director of the state corrections department, is accused of viewing inmates as "property," according to the lawsuit. The attorneys claim in his role, Shinn is degrading the human dignity of each inmate by making a profit. The state is granting the private prisons full power over the inmates and "the fruits of prisoners' economic value and labor," according to the lawsuit. The attorneys argue the private prisons have a financial disadvantage when inmates are released but can receive profit by their incarceration. The lawsuit said the facilities have created biased administrators and have become similar to "slave jails," also known as convict leasing. After the end of the Civil War, convict leasing was practiced in southern states. States leased inmates to companies and plantations. Inmates received little earnings, unlike the states, according to the Equal Justice Initiative. When the Thirteenth Amendment was passed, it prohibited slavery and involuntarily servitude. However, it exempted people who were convicted of crimes. The issue of paying inmates in Arizona's public prisons came up at the state Capitol this year. Rep. Kirsten Engel, D-Tucson, introduced a bill that would raise the minimum wage for inmates who work jobs through Arizona Correctional Industries. The bill did not get a hearing. Who operates the facilities? Arizona's private prisons are operated by three companies, GEO Group, CoreCivic Inc. and Management and Training Corporation. The three companies incarcerate more than 90% of inmates in private prisons in the U.S., according to the attorneys filing the suit. Here's where the three operate in Arizona:

All three companies are members of a trade group called Day 1 Alliance. Alexandra Wilkes, the group's spokesperson told The Republic the allegations in the lawsuit are wrong. "The reason governments first began utilizing public-private partnerships in the 1980s was to address unsafe and unconstitutional conditions in the public correctional system — including severe prison overcrowding and aging facilities that were endangering the lives of incarcerated men and women," she said in a statement. Wilkes said private sector contractors have partnered with governments led by Democrats and Republicans. "The notion that they would somehow be engaged in the activity this lawsuit alleges is a terrible smear," she said. The Prison Was Built to Hold 1,500 Inmates. It Had Over 2,000 Coronavirus Cases. Prison overcrowding has been quietly tolerated for decades. But the pandemic is forcing a reckoning. by Dara Lind Jason Thompson lay awake in his dormitory bed in the Marion Correctional Institution in central Ohio, immobilized by pain, listening to the sounds of “hacking and gurgling” as the novel coronavirus passed from bunk to bunk like a game of “sick hot potato,” he wrote in a Facebook post. Thompson lives in Marion’s dorm for disabled and older prisoners — a place he described to ProPublica in a phone call as the prison’s “old folks home” — where 199 inmates, many frail and some in wheelchairs, were isolated in a space designed for 170. As the disease spread among bunks spaced 3 or 4 feet apart, Thompson said he could see bedridden inmates with full-blown symptoms and others “in varying stages of recovery. While the rest of us are rarely 6 feet away from anyone else, sick or not.” “Prison is not designed for social distancing,” said Thompson, who is serving a de facto life sentence (his first parole hearing will come in 2087) for aggravated murder and kidnapping. “That’s not the system’s fault. That’s not the prison’s fault. It couldn’t have been designed with the vision of one day having to the social distance for 6 feet. … It squeezed as many of us in here as it could.” Nationwide, Marion ranked as the largest recorded coronavirus outbreak of any U.S. institution in a New York Times analysis. Three other prisons, including another packed one in Scotia Township, Ohio, were in the top five. The fifth is the Smithfield pork processing plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. With fears that the second wave of infection will erupt in the fall, some state corrections officials are realizing the coronavirus is a wake-up call, forcing them to confront the problem of prison overcrowding. They’re considering how to achieve social distancing in confined spaces, where inmates are unable to do the only thing that has proven effective in stopping the viral spread. States and the federal government responded to the initial onset of the coronavirus by releasing some individual prisoners who were particularly vulnerable, although ProPublica found the federal directive was undermined by the secretive Bureau of Prisons guidance limiting early release. But even when it looked like the first wave of the coronavirus was subsiding outside prison walls, cases in prisons and jails kept climbing. A Times analysis found a 68% increase in prison and jail cases in May. In light of this, experts are going further than calling for case-by-case releases, acknowledging that prisons simply have to hold fewer people overall. Pennsylvania Corrections Secretary John Wetzel told ProPublica that he expects his state to incorporate the need for social distancing into its definition of what a facility’s acceptable operating capacity is. Staying under the new capacity limits will require prison populations to be reduced. “When you look at this objectively, you have to reduce the population,” Wetzel said. “Because it’s not realistic to say, for the next 12 months, the whole system in Pennsylvania is going to be locked down so we can mitigate the spread.” Reducing populations has proven challenging in states like Ohio, where the overall prison population has declined while the inmate count at Marion has increased. When Ohio addressed overcrowding of female inmates by converting a minimum-security men’s prison into a second women’s prison, some of the displaced men were sent to Marion instead; the same thing happened when the state closed a minimum-security prison for cost reasons in 2018. Looming fiscal crises in states across the country are ratcheting up the pressure to further cut prison budgets, and efforts to build more prisons are on hold.Ohio has shelved plans to rebuild the overstuffed Pickaway Correctional Institution (site of the second-largest recorded coronavirus outbreak in the Times analysis) and has no current plans to permanently address overcrowding at Marion. The Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction has defended its approach to the coronavirus outbreak and answered several questions from ProPublica about specific allegations from inmates. On the issue of overcrowding in general, spokeswoman JoEllen Smith said: “The challenge of any correctional agency is to keep up with the demands of the courts and the criminal justice system. Space allocation has been and will always be a challenge for any correctional system across the country.” Overcrowded prisons are nothing new. But while Ohio’s overall prison population is the lowest it has been in since 2006 because of modest criminal justice and sentencing reforms, Marion’s numbers have grown over the last decade, from 2,300 in March 2010 to 2,538 at the end of March 2020, according to official reports. Ohio stopped reporting the capacity estimates of its prisons to the U.S. Department of Justice in 2015, but an inspection that year showed Marion approaching twice its official capacity. More recent figures show Marion was at 153% of that capacity at the end of March, on the eve of the coronavirus’s arrival. The ODRC’s Smith told ProPublica that Ohio no longer used that capacity measure, because “the design of a facility 60 years ago is not meaningful today due to the changing nature of the populations.” The same dynamic has played out in other states. Thirty-two states reduced their prison capacity from 2011 to 2018, according to a ProPublica analysis of federal data. Prisons in 21 of those states became, on net, more crowded as a result. Eighteen states that had closed prisons were at or above 100% of their remaining facilities’ official capacity estimates. (Ohio is not counted in this analysis. It is one of two states, along with Connecticut, that do not report any capacity numbers to the federal government. The ODRC’s Smith told ProPublica that Ohio stopped calculating capacity because “there is no longer a national standard.”) The inmates in those overstuffed prisons became kindling in the coronavirus fire. “The only thing that we have found that works right now, while we don’t have appropriate therapeutics and we don’t have a vaccine, is social distancing,” said Brie Williams, director of the Criminal Justice & Health Program at the University of California, San Francisco. “And in order to do that, you have to be able to get the physical distance between people to make it happen.” By the time Marion conducted mass testing in late April, the state reported that over 2,000 prisoners — about 80% of the population — had contracted the virus. Prison authorities concluded that it was easier to isolate infected prisoners by keeping them in their assigned dorms and cellblocks and moving the few healthy prisoners into the gym. Marion’s high infection rate outraged inmate Jonathan White, a self-described “news junkie” who took advantage of the prison’s temporary addition of CNN and Fox News to the TV options to educate himself about the virus, even as he recovered from it. Ohio recorded 76 prison coronavirus deaths as of June 12, including 35 at Pickaway and 13 at Marion. Both facilities are overcrowded. Pickaway, like Marion, was over 50% above the last-recorded capacity estimate as of the end of March. Thompson said he had only a vague sense of what was happening around him as the sickest were carted out and prisoners were moved around as test results came back. When a Marion guard died of the coronavirus — the first fatality of any guard or inmate in the state — on April 8, he heard the news from his girlfriend in a phone call. “A week or so later,” he said, “they had a moment of silence for his passing.” Thompson himself was initially told he’d tested negative; he spent two nights in the gym, where, he said, cots were actually spaced 6 feet apart. Then he and a few other inmates were told there had been a mistake — they were infected and had to move back to their original dorms and cellblocks. The reversal devastated Thompson, who told ProPublica he’d spent years trying to get over a reflexive distrust of prison or medical authorities. “I am not ashamed,” he wrote in a May Facebook post, “to admit to having had thoughts of suicide.” In most states, there’s officially no such thing as an overcrowded prison, since there’s no limit to how many people can be put in a facility. The federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, the DOJ arm that collects state criminal justice data, has three metrics for measuring prison capacity. In practice, all of these are subjective assessments made by a state’s prison officials. Even so, many prison systems are at or over 100% of reported capacity. When state budget crunches hit, as they did during the 2008-09 Great Recession, they can close prisons whether or not their prison population is actually declining. And closing a prison is quicker, and less controversial, than passing a bill to shorten future prison sentences (or offer good-time credits for current prisoners) in the hopes of reducing incarceration down the road. A 2016 RAND study found that 31 states had closed prisons between 2007 and 2012 because of budget constraints. The most common response to budget crunches, RAND found, was closing facilities and then cramming more inmates into the remaining ones. Since 2004, Michigan, for example, has closed prisons that held more than 15,000 beds while adding about 5,000 beds to the facilities it kept open. (Chris Gautz, a spokesperson for the Michigan Department of Corrections, told ProPublica that since 2010, all prison closures have been offset by reductions in the inmate population. Phillip Garcia was in a psychiatric crisis. In jail and in the hospital, guards responded with force and restrained the 51-year-old inmate for almost 20 hours, until he died. Warning: graphic video content. In states like Ohio, where incarceration rates were still growing in the late 2000s, adding beds stalled the need for new prisons but came at a cost. “Crowding gives the state a perverse bargain,” the then-director of the Ohio Sentencing Commission wrote in a 2011 report. “Extra inmates add relatively little to total costs. Adding inmates in an over-capacity system only costs about $16/day in food, clothing, and medical care.” Adjusting for inflation, ODRC reports analyzed by ProPublica show that the per-day cost to house an inmate in an Ohio prison dropped from $90.55 (2019 dollars) in 2005 to $80.68 in 2019. A Supreme Court ruling in 2011 — the same year that Ohio’s Legislature passed a criminal justice reform package — was supposed to mark a turning point for prison overcrowding. That June, the court upheld a lower court ruling that overcrowded prisons in California violated the constitutional ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” Advocates hoped the ruling would push other states to reduce their own prison populations or embolden judges to release prisoners if conditions got too egregious. But legislative reforms didn’t always significantly reduce prison populations. In Ohio, it took four years for incarceration numbers to decline. As prisons approached 130% of capacity in 2016 — the level at which experts agree overcrowding becomes an urgent problem — Ohio still declined to build new prisons or release prisoners. In 2018, once incarceration had edged downward, it closed an 800-bed minimum-security prison in southeast Ohio and forced other minimum-security prisons like Marion to absorb more inmates. During the prison-building boom of the 1980s and 1990s, many states shifted from individual cells to dorm spaces. Dorms offered the “cheapest way to warehouse people,” said Joanna Carns, the former head of Ohio’s Correctional Institutions Inspection Committee. Carns resigned from the Ohio post in 2016 under pressure from the Legislature, which criticized her for going beyond her mandate of inspecting individual prisons by analyzing statewide issues like overcrowding. She is now the lead corrections ombuds for the state of Washington. The American Correctional Association, the prison accrediting body, tried to discourage dorm housing 30 years ago, stressing that “the number of inmates rooming together should be kept as low as possible.” But the “dollars and cents” logic of dorms, as Carns put it, was too appealing. Compliance with ACA standards generally gives state prison officials some protection in Eighth Amendment lawsuits from inmates claiming prison conditions are “cruel and unusual.” But even the 2011 Supreme Court ruling, declaring California’s overcrowding an Eighth Amendment violation, based its determination on prison officials’ capacity estimates, not personal space. A series of letters from detainees in one of America’s largest jails reveals the mounting dread and uncertainty as the coronavirus spreads inside the 7,500-inmate facility. With little pressure to protect inmates’ space, even the ACA over the years decreased its recommended square footage per inmate in cells holding multiple prisoners from 50 square feet in 1984 to 25 square feet in 2012. “Nobody is going to let you build more than the minimum standard requirement,” said Andrew Cupples, an architect with the DLR Group, a prison design and consulting firm. Advocates have argued for years that overcrowded prisons threaten inmate health. This was the core argument in the 2011 Supreme Court decision about California: that the state could not adequately provide health care in a prison with twice as many inmates as it was supposed to have. And experts had long ago learned that controlling disease outbreaks in prison is a prerequisite to controlling them elsewhere. “A locus of HIV infection was in prisons and jails. And we really were not able to get control of the epidemic in the United States until people began to focus their attention on getting control of the epidemic inside prisons and jails,” Williams, of UCSF, told ProPublica. “Same for hepatitis C, same for tuberculosis.” Prison architects assume that medical staff can treat any infectious disease that gets in. They don’t design facilities for large numbers of people suffering a new and mysterious disease. The novel coronavirus was something prisons, literally, were not designed to manage. Overcrowding was a concern at Marion long before Thompson arrived there. Prison management noted in a 2011 inspection report that “the increase in population” had so badly overloaded the water system that hot water was unavailable at peak shower times. Smith, the ODRC spokeswoman, said the issue was fixed in 2016. In recent years, multiple inmates told ProPublica, the ceiling of the ground-floor dorms would shake when the inmates above got out of their bunks after daily roll call. When the coronavirus surfaced, Marion and other packed prisons and jails had no good options for isolating potentially sick inmates — or quarantining them. According to the Marion Star, the prison had nine infirmary beds to serve its 2,500 prisoners. Once those beds were filled, inmates who raised concerns about coronavirus symptoms were sent to the prison’s only other secluded part: solitary confinement. Inmates at Marion told ProPublica that isolation cells — known as “the hole” — are regarded as punishment and avoided at all costs. One inmate told ProPublica that during a brief stay in medical isolation, he lost phone privileges. Others said that they did not report virus symptoms to prison staff because they didn’t want to spend time in solitary. In March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned prisons that inmates’ fear of medical isolation could encourage the virus’s spread. Correctional officers, health care staff, and detainees describe how COVID-19 spread through Cook County Jail in Chicago as the sheriff came under fire for his handling of the crisis. “You’re working in a petri dish,” one staffer said.

When Marion ran out of cells in “the hole,” it packed potentially infected inmates into classrooms, 20 to a room, to sleep. (In many other overcrowded prisons and jails, that wouldn’t be possible — spaces like classrooms and recreational areas have already been turned into bed space.) Finally, the prison grouped all inmates into clusters of 100 to 120 men, based on the dorms or cellblocks they were already living in, and then tried to keep the “households” isolated from each other. Marion officials made fruitless attempts to create space. Hallways were marked off with spots 6 feet apart as a guide for inmates walking outside of their cells. “We’ve all just gotten up from being in bed areas that were 2 feet apart from each other all day,” inmate Jonathan White recalled. The ODRC insists that while the whole facility was under isolation, every inmate got a daily temperature and symptoms check. “The only individuals who were not symptom screened during this time period were those who were recovered patients,” Smith told ProPublica. But all 10 inmates interviewed by ProPublica described infrequent temperature checks and said they were not routinely asked about other symptoms. One inmate, who asked to remain anonymous to protect his future chances of parole, told ProPublica he had never been asked about symptoms beyond fever. Chris Mabe, the head of the Ohio Civil Service Employees Association, which represents Ohio prison guards, told ProPublica he believed daily checks were unlikely. “We’ve been understaffed and overpopulated for decades in the state of Ohio,” he said, and the coronavirus exacerbated staffing shortages. “I just can’t believe that every day that there are five or six people for medical walking around having interviews with 2,000 or 3,000 inmates to see if they’re symptomatic.” By late May, Marion was slowly returning to normal. As of May 21, the ODRC reported that 2,101 of Marion’s inmates had recovered from COVID-19. By June 12, that number had declined slightly to 2,088. Many areas of the facility have allowed inmates to move around normally at mealtimes, though the Americans with Disabilities Act-compliant dorm, where Thompson lives, is still under restricted movement. In theory, masks are mandatory, but some inmates have stopped using them and say guards do not appear to be enforcing the rule. The ODRC’s Smith told ProPublica that “if an individual is found to not be wearing his mask, he is asked and reminded to put it on.” Thompson is still wearing a mask everywhere. The coronavirus outbreak, and the emotional roller coaster of believing he’d tested negative and then being told the opposite, has made him “paranoid.” He’s washed his cloth masks so many times that the cotton has begun to fray. Ohio, like many states, used emergency powers to try to thin out prison populations during the outbreak. The result: From March 24 to May 5, Ohio’s prison population shrunk by about 1,582 prisoners — a 3% decline. Although Marion has an older population than most state prisons, inmates there did not hugely benefit from the release policy. The prison’s population dropped by 76 prisoners or the same 3% as elsewhere. The reason is simple. Older inmates are often serving long sentences for serious crimes, and governors and state legislatures are still afraid to release violent criminals even if their crimes were committed decades ago. The prisoners most vulnerable to the coronavirus are among the least likely to be released by either emergency clemency or many reform bills. Meanwhile, building new prisons is almost certainly out of the question. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, like most other governors, is looking ahead to drastically reduced tax revenues and already making deep budget cuts. Before the coronavirus, Ohio was accepting bids to build a new prison to replace Pickaway. “For the planning of the new facility, everybody agreed, give people some living space so that they can self-separate,” Cupples, the architect, told ProPublica. But in April, because of the expected budget shortfall, the state government rejected all bids for the project. “The Pickaway project was delayed until further information is provided on Ohio’s capital bill,” Smith confirmed to ProPublica. Ohio will keep making do with what it has. This is bad. Really bad.

Fox News’ website published digitally altered photos that made it seem as if a demonstration in Seattle was violent and dangerous, when in fact, it was nothing of the sort. In an editor’s note, Fox News apologized — sort of — but the damage had already been done. It started when Fox News’ website ran a photo that was supposedly from Seattle with the headline “Crazy Town.” That photo — a man running in front of a burning building — was actually from St. Paul, Minnesota. Another photo of a man holding an assault rifle was digitally added. There’s no other way to put this: These are fireable offenses. They are inexcusable. This is no different than completely making up a story — which many (me, included) consider to be the worst offense in journalism. And Fox News’ website might have gotten away with this reprehensible behavior had it not been caught by The Seattle Times. Fox News only removed the images after being called out by the paper. In an emailed statement to The Seattle Times, a Fox News spokesperson said: “We have replaced our photo illustration with the clearly delineated images of a gunman and a shattered storefront, both of which were taken this week in Seattle’s autonomous zone.” But The Seattle Times’ Jim Brunner wrote, “That statement is inaccurate, as the gunman photo was taken June 10, while storefront images it was melded with were datelined May 30 by Getty Images.”

ABA President Martinez decries violence against George Floyd, Black community.

Pledges action

Statements on George Floyd Death and Protests

Following are bar organization statements regarding the death of George Floyd and the subsequent protests. National Bar Organizations

California

The nation’s leading journalism and press freedom organizations today called on law enforcement, mayors and governors across the country to halt the unprecedented assault against journalists in the field covering the protests for social justice.

The following open letter to police nationwide was signed by 28 organizations including: The National Press Club (NPC), The National Press Club Journalism Institute (NPCJI), Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, National Association for Black Journalists (NABJ), Journalism & Women Symposium (JAWS), Pen America, NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists, News Media Alliance, National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), RTDNA, Freedom House, Online News Association, News Leaders Association, National Press Photographers Association (NPPA), National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ), Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), International Women’s Media Foundation, Asian American Journalist Association, The NewsGuild-CWA, National Federation of Press Women, National Press Foundation, College Media Association, Student Press Law Center, Texas Intercollegiate Press Association, Texas Community College Journalism Association, and the Radio & Television News Association of Southern California. First, you have our utmost respect. The job you are being asked to do is difficult and requires extraordinary courage and discipline and we can see that most of you are working diligently to restore a sense of peace and calm to your cities. Thank you for your best efforts. Still, we need something more. You must persuade your colleagues, commanders and chiefs, and the mayors and governors who direct them, to halt the deliberate and devastating targeting of journalists in the field. We are at a crossroads for our nation. Over the past 72 hours police have opened fire with rubber bullets, tear gas, pepper spray, pepper balls and have used nightsticks and shields to attack the working press as never before in this nation. This must stop. This is against all training and best practices of policing. Your Public Information Officers have spent countless hours training in how to best proceed in these circumstances. Now is the time to put that training into action. A few years ago in Ferguson, Missouri, police attempted some of these tactics and they failed. Courts found against governments that illegally arrested journalists and then tried to ban them from their state. It was devastating for Missouri’s reputation. This will happen again. We are addressing here law enforcement in Minneapolis, Philadelphia, Las Vegas, Denver, Fargo, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, Seattle, Washington DC and other cities. When you silence the press with rubber bullets, you silence the voice of the public. Do not abandon our Constitution and its First Amendment. And above all do not abandon your training. You are professionals. You have been trained in how best to work with journalists in the most trying circumstances. That is not happening here. Talk to your PIOs. Talk to your commanders. Talk to your officers, the men and women to your right and your left. Be leaders. Do not fire upon members of the working press. We are in this together. These cities belong to all of us. The people that live in them will learn of your bravery and courage and training through news coverage by journalists. Do not fire upon them. Do not arrest them. The world is watching. Let the Press tell the story. Images of some American farmers dumping milk, plowing under crops and tossing perishables amid sagging demand and falling prices during the deadly coronavirus pandemic has made for dramatic TV.