|

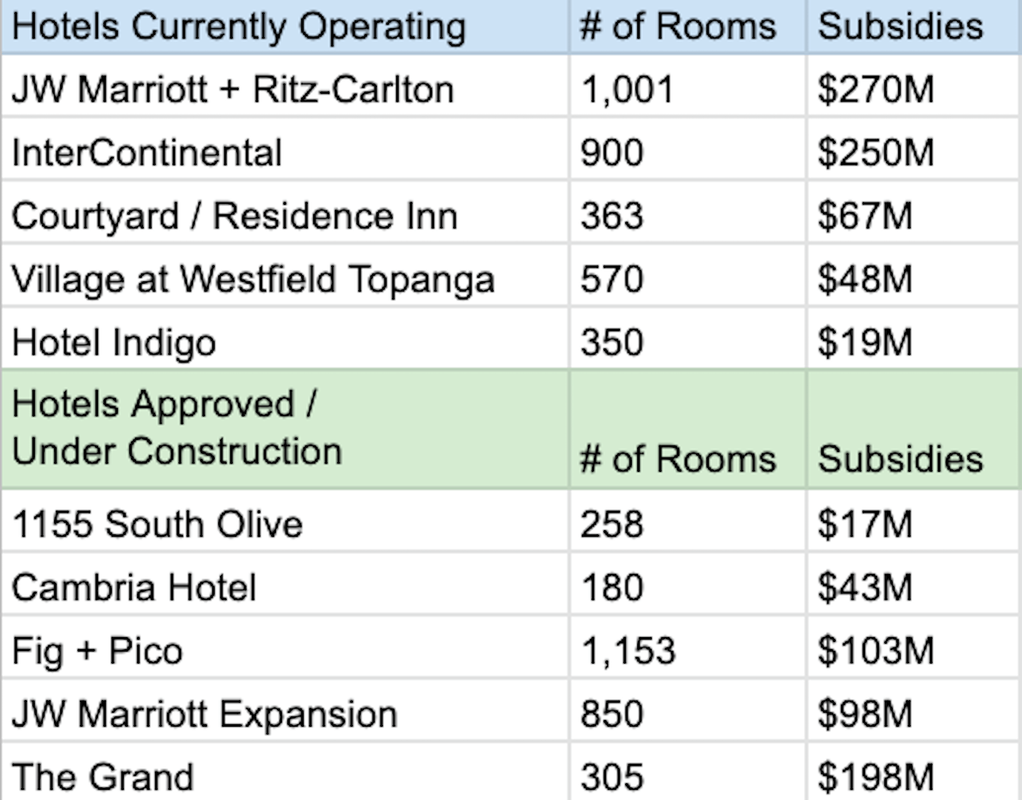

Tens of thousands of people in Los Angeles County are at high risk for becoming homeless after the temporary halt on evictions is lifted—one of the largest mass displacements the region has ever seen.  Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the numbers have been dizzying. Infection rates. Deaths. Unemployment claims. The numbers tell the story of structural racism, with rising burdens of disease, death, and dispossession borne disproportionately by Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities. They reverberate through the national uprising for Black lives and racial justice, which also recounts numbers—of killings and excessive force by police, and of the millions of dollars allocated to bloated police budgets. We, too, are concerned with numbers. Ponder this: In January 2020, prior to the economic and social devastations wrought in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, 66,436 people were experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County, a region with approximately 10 million people. Seventy-two percent of them were unsheltered. Our UCLA colleague, Gary Blasi, estimates that once the halt in evictions due to the COVID-19 emergency is lifted, 365,000 renter households will be in imminent danger of eviction in Los Angeles County. Of these, as many as 120,000 renter households in Los Angeles County, including 184,000 children, are at high risk of not only being evicted but also becoming homeless. The lowest projection provided by the Blasi report is 36,000 newly homeless households, including 56,000 children. This will be one of the largest mass displacements to unfold in the region. Meanwhile, Los Angeles, emblematic of the inequalities that structure life and death in the United States, is gripped by political inertia. Public officials at all levels of government have failed to enact policies that would protect tenants from displacement. In 2018, the Economic Roundtable reported that nearly 600,000 Los Angeles County residents were not only in poverty, but were also in households spending 90 percent or more of their income on housing. That was in the time of robust employment and somewhat stable incomes. Now these households are on the brink of disaster, having to make the choice between food or rent, most likely unable to afford either. Where will the currently unhoused and the newly unhoused go? Decades of disinvestment in low-income housing and investment in policies of gentrification and luxury urban development have created a crisis of housing insecurity that now conjoins with the political failure to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. The construction of new affordable housing in Los Angeles has been excruciatingly slow, and the waiting lists for housing vouchers are painfully long. But here’s another set of numbers. There are over 100,000 hotel and motel rooms in Los Angeles County that serve tourists. Hotel industry estimates indicate that, given the downturn in the global tourist industry, around 70,000 of these rooms will lie vacant for several years to come. Moreover, many hotels and motels will most likely never recover because of their debt structures. Such distressed properties will most likely be bought up by Wall Street actors such as the Blackstone Group, which went on a buying spree in the wake of the Great Recession and purchased budget motel chains such as Motel 6. Especially vulnerable are the neighborhoods that are already on the front lines of gentrification, where property ownership is shifting from communities to corporations. Often places with long histories of exclusionary and predatory finance (redlining and subprime loans), these were hotspots of foreclosure during the Great Recession. In this round of crisis, they are at risk of more wealth loss. The public already has a stake in the county’s hotels. A chunk of these vacant rooms are in publicly subsidized hotels, or hotels whose development has relied on public sector investments, financial incentives, tax rebates, and deferrals, as well as land assembly through eminent domain and redevelopment. Just in downtown Los Angeles, the financial costs of such subsidies amounted to $1 billion between 2005 and 2018, and the city has committed at least $114 million more since then in poorly negotiated deals. These numbers, of course, do not include the incalculable human costs of displacement nor the impact of diverting these resources away from the provision of housing, schools, libraries, parks, and many other necessities that LA’s working-class communities of color sorely lack. And what did Angelenos get in return for these gigantic corporate handouts? Increasingly unaffordable, over-policed neighborhoods. The largest subsidy, a whopping $270 million for the Ritz-Carlton and JW Marriott at LA Live, was gifted to AEG to create 1,001 rooms, representing roughly 1 percent of the overall county stock. At the same time, many of our local officials are embroiled in obscene developer-driven corruption scandals, in addition to the influence that developers openly wield at City Hall, while homelessness and housing precarity have skyrocketed. In our recently released report, “Hotel California: Housing the Crisis,” we do the math. Inspired by housing justice movements that have drawn attention to the cruel paradox of vacant property while thousands of people experience homelessness or housing insecurity, we advocate for the public acquisition of vacant tourist hotels and motels in Los Angeles and a shift in their use from hospitality to housing. Here is the opportunity to significantly enact the mass expansion of low-income housing, and to even convert such property into social housing. No other existing mechanism of housing provision in Los Angeles can add this many housing units at a reasonable price point and in a relatively compressed timeline. The time is one of reckoning. As the national uprising for Black lives and racial justice intersects with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear that the human suffering, so poignantly visible through protest and outrage, is state-sanctioned and never inevitable. It represents a conscious policy choice. But it does not have to be this way. In Los Angeles, as in other U.S. cities, publicly subsidized hotel development has been underwritten by what urban studies scholars have called “geobribes”—largesse from public coffers distributed to global corporations and real-estate developers in the (rarely met) hope of spurring economic benefits. Accompanying such subsidies have been institutional forms of displacement and social cleansing, from Business Improvement Districts to zero-tolerance policing. It is time to redirect public resources and public purpose tools such as eminent domain for housing, especially for Black and Latinx communities where public investment has primarily taken the form of policing and where the devastation of impending evictions will be most acutely felt. Spatial justice is the urgent task at hand. If it does not seem possible to imagine the acquisition and conversion of vacant tourist hotels and motels into social housing, then it is worth reflecting on how the present moment of compounding crises has broken past the limits of the possible. In California, Project Roomkey is both a statewide and local program to use vacant tourist hotels and motels as shelter for people experiencing homelessness during the pandemic. In Minneapolis, amid the protests following the murder of Mr. George Floyd, who himself worked as a security guard in the state’s largest homeless shelter, the unhoused came together to create a community in a vacant Minneapolis Sheraton Hotel. The Minneapolis experiment was short-lived, and because Project Roomkey is reliant on negotiated occupancy agreements with hotels rather than on the commandeering of property, an emergency power that rests with government executives, it has failed to meet its targets. But both hint at what could be possible with more political will. The relationship between property and housing is a complex one. From Indigenous dispossession to financial speculation, it has been a key logic of inequality in the United States. But the vacancy and indebtedness of property presents an opening to reconsider its use and ownership for a social purpose: housing. Ananya Roy is professor of urban planning, social welfare, and geography at UCLA and director of the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy. Her research and scholarship is concerned with housing justice and racial justice. Jonny Coleman is a writer and organizer with NOlympics LA.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed