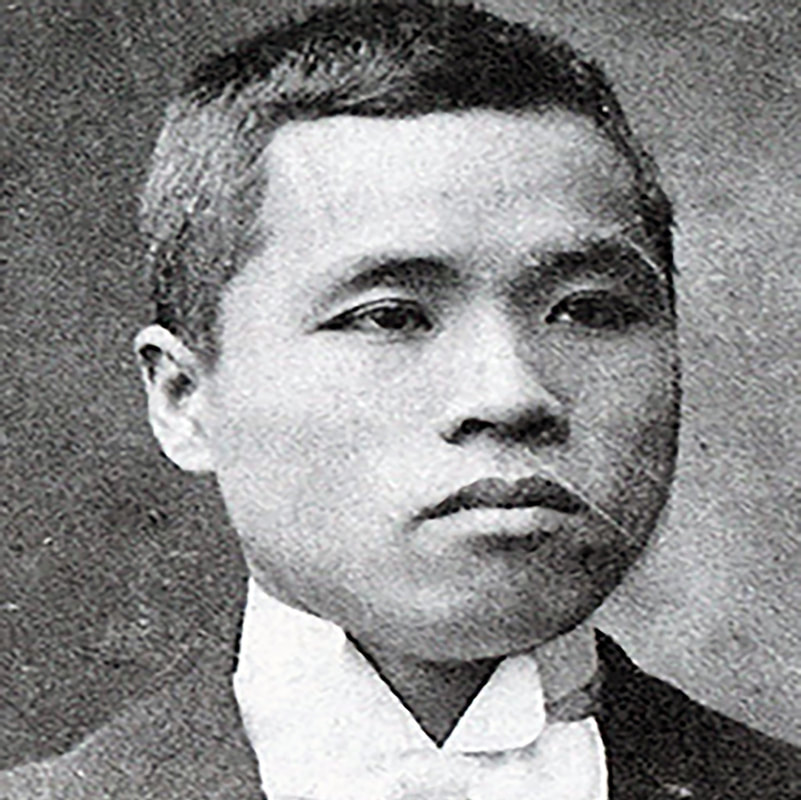

|

Takuji Yamashita earned his law degree from the University of Washington in 1902. He was awarded U.S. citizenship that year and then had it stripped away by the Washington Supreme Court because of his Japanese birth. The ruling also denied him admittance to the Bar, so Yamashita went into business and farming. He would later join a U.S. Supreme Court appeal to try to reverse the ban on Asian immigrants. FAMILIES TRAMPLED FLOWERBEDS for the best view. Youngsters perched on roofs. An Army band pumped out The Star-Spangled Banner, then explosions cracked the sky over Elliott Bay.

“One of the most magnificent pyrotechnic displays ever seen,” gushed The Seattle Times. It was July 4, 1907, and the instigators were as striking as the incendiaries. Seattle’s Japanese community had won hosting honors to dazzle the city with “Oriental” fireworks unloaded from the NYK freighter in the harbor below. The gunpowder came with an agenda. Before bombs burst in air, the immigrants sent their best orator to the stage. Born in a remote Japanese fishing village, Takuji Yamashita had sailed through law school in Seattle only to be blocked from becoming a U.S. citizen and practicing law. Now, on Independence Day, he delivered a speech so radical for 1907, it made the next day’s papers. People from Asia, Yamashita declared, could bring prosperity to places like Seattle — but only if Americans dealt them in as equals. “You have a great duty to elevate others to the same plane as yourselves,” he told the crowd, as quoted in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Let nobody in this country be denied right and justice.” Yamashita’s words soon faded like fireworks in the sky, but the long-forgotten Northwesterner — and the civil-rights movement in which he took part — cries out for a fresh look in a time of reckoning on race. Yamashita and his allies waged key battles against the creed that whiteness makes an American. WHEN YAMASHITA WAS born in 1874, Japan was shaking off centuries of isolation. Emigration was legalized the year he turned 12. When he was 14, Christian missionaries opened a church in his town, Yawatahama. After graduating from the prefecture’s most rigorous high school in 1893, he wrote his parents a letter promising to “try to walk the path of honor” across the sea. Snow-capped Mount Rainier, Fuji’s brawny American cousin, welcomed Yamashita to the Northwest. The 19-year-old waited tables at a countryman’s greasy spoon in Tacoma, slept at the Japanese Baptist Mission and raced through Tacoma High with top grades in everything but spelling. Next came the University of Washington’s new law school in downtown Seattle. Around a potbelly stove, students reviewed cases under the famously stern eye of Dean John Condon. The yearbook dubbed Yamashita a “Stranger in a Strange Land” but also declared him the star of the school’s moot court. At a banquet after passing the 1902 Bar exam, Yamashita titled his speech “The Making of an American.” That was premature. CONGRESS HAD LAID a path to citizenship in 1790 to any “free white person.” After the Civil War, it added people of African birth or descent. Yamashita clearly was not African, but what was a “free white person?” Judges ruled with wild inconsistency on aspiring Americans from Syria, Mexico and other non-European locales. By the time Yamashita came ashore, a federal judge had turned thumbs down to Shebato Saito of Japan, but some local judges still accepted Saito’s countrymen. This muddle prevailed on May 14, 1902, when Yamashita left the Pierce County Courthouse holding his naturalization certificate. He needed it — U.S. citizenship was a requirement for practicing law — and he got the right judge to sign it: an ex-lawyer for a railroad that was bringing in workers from Japan by the hundreds. But the state Supreme Court, gatekeepers to the Bar, held up Yamashita’s admission. State Attorney General W.B. Stratton declared that the young graduate’s Asian origins disqualified him. Yamashita fought back with the Declaration of Independence, arguing in a memorable brief that to reject a person of good character because of race would affront the core values of “the most enlightened and liberty-loving nation of them all … in which all men are equal in rights and opportunities.” “Worn-out Star-Spangled Banner orations,” Stratton responded, did not make Yamashita a member of the white race. The five justices nullified Yamashita’s citizenship, ending his legal career before it began. THREE MONTHS LATER, Yamashita posed in a studio next to his new bride, Ito Nakagawa, a grain trader’s daughter from his hometown. The newlyweds presided over the Klondike Hotel, one of 60 boardinghouses in Seattle’s Japantown — a northern slice of today’s Chinatown International District — a neighborhood thrumming with 18 tailor shops, three banks, two daily papers in Japanese and a baseball team. Yamashita had stature here. He presided over a debating society of educated Japanese people and founded an Ehime immigrants association that survives today. From time to time, he welcomed Japanese delegates planning the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the 1909 World’s Fair that would proclaim Seattle the nexus of the frozen North and exotic East. In June 1907, workers broke ground for the fair’s Japanese Village, homage to a rising power whose cultural curiosities were all the rage. When The Seattle Times encountered a touring sumo wrestler that spring, it reported with wonder that, “He eats most of the time he is not drinking.” Beyond the titillation lay superhuman menace. “A Japanese coolie,” declared The Argus, a Seattle weekly newspaper, “can live on wages on which a white man would starve to death.” Racial tropes (such as the use of the word “coolie,” a now-outdated and offensive term for unskilled laborers) crossed with abandon: the Japanese worked like machines and wallowed in an opium haze; their homeland was a primitive backwater and threatened world domination; they were incapable of assimilating and unwilling to do so. Through this fog of fear and fascination sailed NYK’s Shinano Maru, bearing fireworks for Seattle’s 1907 Fourth of July. More than 10,000 spectators, according to The Post-Intelligencer, gathered for the patriotic show near today’s Kerry Park on Queen Anne Hill. That crowd count might be inflated, but photographers captured a sea of straw hats and bonnets. Seattle’s population had tripled in the decade since NYK (Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha) made the city its main U.S. port; Japan had helped build the Northwest. In his keynote address, Yamashita told the crowd this was just the beginning. “We hope to see this country prosper,” he proclaimed on behalf of his fellow Issei, or Japanese immigrants. “As it prospers, we prosper.” The Post-Intelligencer praised Yamashita’s words as “an answer to the agitators who perpetually preach the dangers of a Japanese peril,” but agitators held increasing sway. To appease them, President Theodore Roosevelt cut a deal that year with Tokyo: No more Japanese workers could come, but wives could join settlers already in the United States. The upshot: a Japanese-American baby boom. In Seattle’s Japantown, four midwives sprang into duty night and day. Because a child born on U.S. soil is a citizen by birthright, Japanese immigrants were having baby Americans. Roosevelt’s deal drove agitators to a new level of rage. At the 1908 International Exclusion League convention in Seattle, an American Federation of Labor official declared that the Stars and Stripes would never have “a yellow streak.” WHEN THE CAMERA clicked on Independence Day 1913, Yamashita stood watching the parade with three fidgety children by his side. His growing family had moved to Bremerton, where the shipyard repaired vessels for the looming Great War. At the Yamashitas’ Togo Hotel, workers occupied all 12 rooms, and the storefront barber collected 35 cents a cut. Legal acumen was as crucial as filling beds. The Yamashitas ran the Togo through a corporation fronted by a pair of white Seattle lawyers. The state constitution barred noncitizens from owning land unless they “in good faith have declared their intention to become citizens of the United States.” Yamashita had famously declared that intention, only to see his citizenship stripped away. His brother Jirosaku — who arrived in 1905 with his wife and son — farmed berries in Pierce County, an area The Seattle Star said the Japanese were “overrunning.” Barred from owning land, Japanese people signed crop contracts for the right to wrestle white people’s stumps and swamps into productive farms. Fueling this Issei toil was the dream that birthright citizenship would lift their U.S.-born children, known as Nisei, to secure footing. But politicians kept planting new obstacles. In 1921, Washington state banned those ineligible for citizenship from holding land in the name of a minor. Citizenship no longer was a pass to the ballot box or a badge of belonging; it meant survival. Yet attempts to expand citizenship died at the hands of U.S. House Immigration Chairman Albert Johnson, a Tacoma Republican outspoken in his animosity toward Asians. The U.S. Supreme Court was the last hope, and a Honolulu immigrant named Takao Ozawa — an educated businessman, like Yamashita — was hellbent to get there. Ozawa liked to cite Revolutionary War turncoat Benedict Arnold to prove that patriotism had nothing to do with ethnicity. Arnold’s name sounded American, but he had proved a traitor. Ozawa’s name might sound foreign, he told a judge, but, “At heart, I am a true American.” Coming decades before Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to judge people by character rather than color, Ozawa’s parable failed to persuade a superior court, a federal district court or the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. But with alien land laws spreading, Issei leaders agreed to take Ozawa’s case to the top. Yamashita joined as a backup. Because Washington’s highest court had already rejected his citizenship, his appeal would speed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. To activate the maneuver, Yamashita and a Montana railroad man named Charles Hyosaburo Kono created a paper company called the Japanese American Real Estate Corp. — its very name thumbing its nose at Washington’s alien land law. As expected, Washington’s Secretary of State J. Grant Hinkle blocked the corporation, and the state Supreme Court backed him up, citing its old ruling against Yamashita. The U.S. Supreme Court quickly paired the case with Ozawa’s. Victory in the twin cases would pry open a portal to the American dream. Defeat would seal barriers that had been, at times, semipermeable. To borrow from baseball — a sport beloved in Yamashita’s native and adopted lands — Japanese immigrants had been trying to get ahead one base at a time, only to keep losing. Now, their leaders concluded, it was time to swing for the fences. They should have checked the umpires. On Oct. 3, 1922, newly seated Chief Justice William Howard Taft presided over oral arguments in the U.S. Supreme Court. His court would spend the 1920s thwarting a minimum wage, integrated schools and other progressive ideas. But first, it would decide whether Japanese people could become Americans. Forsaking Yamashita’s rights rhetoric of 1902, the Japanese legal team tried science. In an attempt to puncture the law’s arbitrary racial boundaries, treatises traced Caucasian origins in the Ainu people of northern Japan, and found that Japanese individuals could be “whiter than the average Italian.” Science did not sway the court. Justice George Sutherland — an immigrant from England — wrote in the unanimous opinion that individuals’ skin color might vary, but Japanese people were “clearly of a race which is not Caucasian.” The rulings made Asian exclusion explicit. Japanese immigrants had struck out. BACK IN BREMERTON, Yamashita had other problems. Shipyard jobs had sunk to half their wartime peak, forcing him to shutter his boardinghouse. And by 1926, he and Ito had endured the deaths of five of their seven children, from meningitis, tuberculosis and other menaces of the era. The two surviving children grew up on separate shores. Haruko, raised by relatives back in Yawatahama, would bear nine children there. Martha, the family’s American-born citizen, would bounce from the Bremerton High glee club to a stint at UW to her parents’ latest venture: farming. In a lagoon where Dyes Inlet touches the town of Silverdale, the Yamashitas planted oysters from Japan. Ashore they laid tight rows of strawberries almost up to the family’s front porch. Rounding out the scene were an enormous German shepherd, a skinny horse and streams of visiting family and friends. Around the firepit, these guests rarely heard Yamashita lament his hardships; he was more likely to be recruiting for a fishing trip. His framed law diploma, however, told its silent story on the living-room wall. AS THE FAMILY’S U.S. citizen, Martha signed the 1937 contract to purchase the Silverdale farm. The Yamashitas put $500 down, records show, and chipped away at the $2,000 balance with each harvest. They had whittled it down to $1,500 by Dec. 7, 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. President Franklin Roosevelt soon banished everyone of Japanese descent from the West Coast. Soldiers cleared out Bainbridge in March, Seattle in April and Kitsap in May. Facing exile, the Yamashitas deeded their farm back to the seller, who sold it to a white family two years later for $16,000. The Yamashitas spent the next three years at War Relocation Centers — historians call them concentration camps — in California and Idaho. At Tule Lake, Takuji Yamashita swore a loyalty oath to the United States. At Manzanar, he was treated for a heart ailment. At Minidoka, he turned 70; weighed in at 110 pounds; and logged 1,666 hours on the laundry, coal and maintenance crews. When Takuji and Ito Yamashita left Minidoka on May 17, 1945, they moved in as helpers to a white widow in West Seattle, according to relatives and War Relocation Authority records. From the living-room window, they could gaze across Puget Sound and almost see their old farm. If Yamashita was bitter, he did not admit it. “I spend my days in joy and appreciation,” he wrote for a postwar Japanese Baptist Church event. Only one thing could break his spirit. When daughter Martha died of tuberculosis in 1957, Takuji and Ito packed the law diploma and photo albums onto a plane for Japan. In the town of his birth, Takuji Yamashita died on March 18, 1959. It would take him another 42 years to gain admission to the state Bar. CONGRESS ENDED RACE-BASED naturalization in 1952. Washington voters repealed the Alien Land Law in 1966. In the 1980s, America sent $20,000 checks to those it had locked up in WWII camps. By the millennial year of 2000, schoolchildren poked around the desolate camps on field trips. Gary Locke, the grandson of peasants from Guangdong, China, inhabited the Washington governor’s mansion. A Japanese citizen, Ichiro, had signed with the Mariners and was about to become the most popular human being in Seattle. And the UW law school decided to celebrate its centennial by honoring its thwarted early graduate. With the Asian Bar Association of Washington and the State Bar Association, the school petitioned the state Supreme Court to posthumously admit Yamashita to the Bar. The March 1, 2001, ceremony in Olympia would bring Yamashita’s descendants from Japan together with Northwest luminaries in law, trade, diplomacy and civil rights. Nature put one more hurdle in Yamashita’s way. The day before the event, the 6.8-magnitude Nisqually Earthquake rained plaster onto the pews of the Temple of Justice and shut down airports and highways. A fast-fingered travel agent rebooked flights. Two hundred guests found their way to an intact Tacoma courtroom offered by a federal judge. There, state Attorney General Christine Gregoire — successor to Yamashita’s persecutors of the same title — addressed Takuji Yamashita across time. “Today,” Gregoire said, “we can finally say you won.” Yet to come were the Sept. 11 attacks, President Donald Trump’s Muslim ban, family separations, the Wall, Black Lives Matter, and a spate of pandemic-era hate crimes against Asian Americans. As those events show, citizenship can’t right every wrong. But in standing up to the injustices of his day, Yamashita voiced with rare clarity why America must improve — to live up to its own founding principles. His writings and speeches belong in U.S. history texts, beacons to the future as well as the past. Experts debate whether the legal battles waged by Yamashita and his allies advanced their cause or set it back. But for 20 years, a University of Washington scholarship bearing Yamashita’s name has supported law students who promise to devote their careers to human rights.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed