|

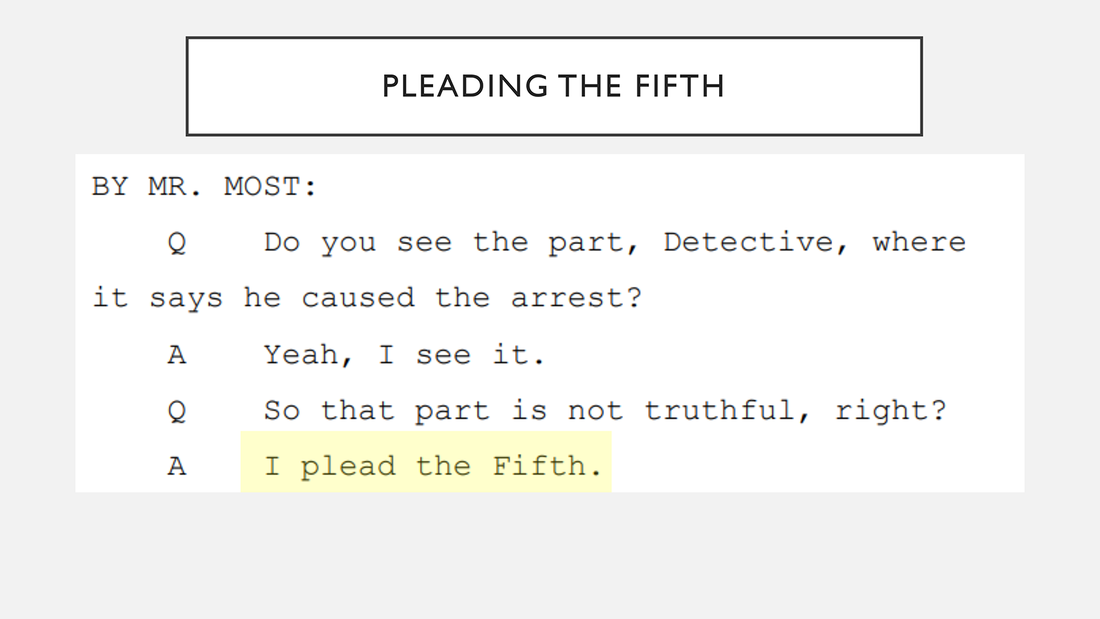

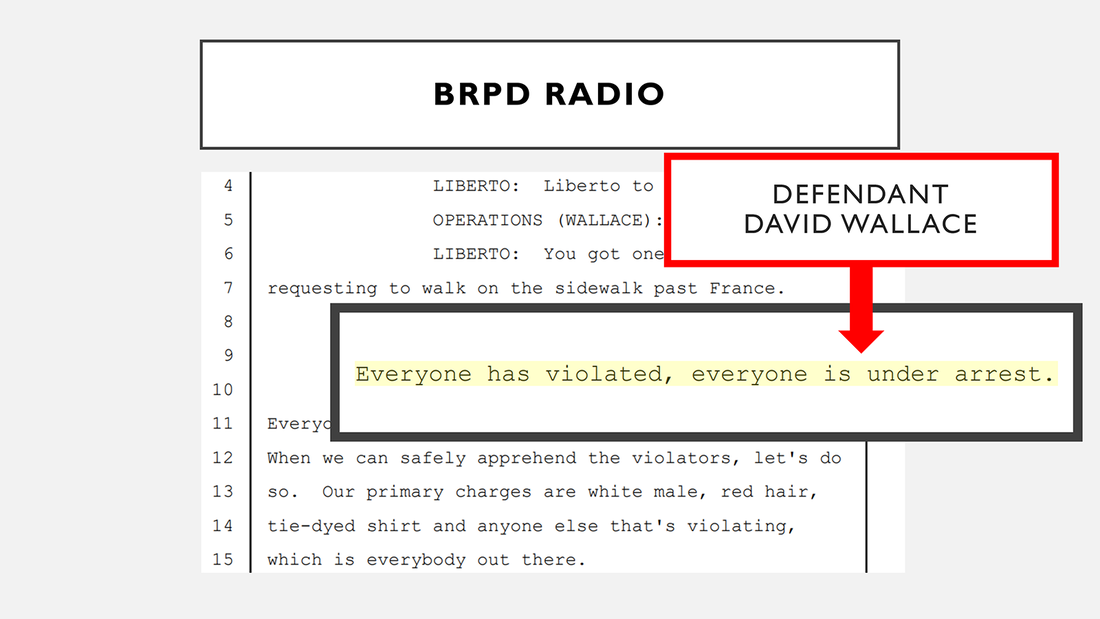

After being strip-searched, pepper sprayed, and spending the night in a cold cell following her arrest at a peaceful protest a day earlier, Cherri Foytlin walked out of a Baton Rouge parish jail on July 11, 2016, to a waiting crowd of fellow activists and friends who welcomed her with water and snacks. While it was a comfort to see familiar faces, a darker thought clouded her mind: that the officers who mistreated her might never be held accountable. The day before, officers with the Baton Rouge Police Department wielding automatic weapons, shielded by body armor and gas masks, and flanked by an acoustic weapon mounted on an armored vehicle swept through a quaint neighborhood in Louisiana's capital arresting dozens of people, including Foytlin, who were peacefully protesting the death of Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old Black man killed by officers of the same department days earlier. Videos and news reports show cops throwing protesters to the ground, pinning them, and locking their wrists with plastic zip ties. Foytlin and several other people who were arrested that day, including Karen Savage, a reporter for Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, and Blair Imani, a queer, Black and Muslim activist, said they were brutalized by cops. "I didn't think there would ever be justice for us. I didn't think it was possible," Foytlin said at a press conference in late February. But when veteran Louisiana civil rights attorneys John Adcock and William Most teamed up to file a pro bono lawsuit a year later on behalf of the arrestees, it gave Foytlin and her peers a glimmer of hope that, one day, the police department responsible for their treatment would be held accountable in a court of law. "This case was important in part because people have a right to protest," Most told Law360. "They have a right to assemble and there's freedom of press. And sidewalks and streets are traditional forums for speech." The case, Imani v. City of Baton Rouge, zeroed in on aggressive BRPD tactics that the protesters said violated state and federal laws.Though the trial opened at the beginning of February, the proceedings came to a sudden conclusion on Feb. 15, one day before jurors were scheduled to hear closing arguments, as the Baton Rouge city council agreed to pay $1.17 million to the 14 plaintiffs to end the dispute. For the protesters and lawyers, the suit was never about money. Instead, they said it was about one of America's sacred rights: to challenge government action without fear of retribution. "So many Americans think if you protest, then you will get arrested. One goes with the other. And that's not the way it is. It's not the way it's supposed to be," Adcock said. "This frightens me." Strong Evidence Made the Difference The attorneys said the strength of evidence pointing to excessive use of force by BRPD officers and alleged falsification of documents ended up being the winning card in the case. "I think the key thing about what got us to this point is they just looked so bad at trial," Adcock said. "It's hard to lie over and over when you have so much video." According to city policy, "any protester who complies with an order to clear the streets should not be arrested by the Baton Rouge Police Department." Yet on July 10, 2016, the plaintiffs were arrested despite complying with police orders, which were sometimes inconsistent, Most said during a press conference at the end of the case. At trial, plaintiffs argued that the police lacked evidence that they had failed to obey orders — first to get off the streets, then to get off the sidewalks, then to disperse. "The testimony at trial was that it was impossible to comply with," Most said. "You cannot at the same time stay out of the streets and disperse from the area, because the only way to leave the area would be by crossing the streets." The plaintiffs presented transcripts of police communications to support their claims that officers were bent on arresting anyone in the area, regardless of where they were standing. Cell phone videos, meanwhile, showed officers entering the front yard of a home without a warrant and arresting a group of protesters who had taken refuge there with permission from the house's owner. In order to book a suspect into the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison, police must produce either a warrant or a sworn affidavit from an officer specifying the crimes a suspect is accused of.

While affidavits need to be filled out after an alleged crime is committed, timestamps on internal BRPD emails showed police arrived at the protest with affidavits that were already filled out with nearly identical facts and charges. "An officer, typically, can only write down what they arrested someone for after that has happened," Most said. Adcock told Law360 that discovery is crucial in determining litigation strategy. And in the Imani case, attorneys were able to compare what was on the affidavits with the actual facts of each arrest, and were able to find a pattern. "A light bulb goes off about, 'There might be something else here to zero in on,'" Adcock said. A Crowd Control Policy Used to Target Speech The plaintiffs presented evidence aimed at showing that BRPD applied a punitive "civil unrest" protocol to crack down on protesters precisely because they were protesting the conduct of its officers in Sterling's killing. Once BRPD decided the protests fell under that policy, officers were required to disperse the crowd, even if peaceful, and were given broad powers to effectuate a mass arrest and to use deadly force, Most said. Former officer Michael Barrow admitted at trial that the policy was applied to the protesters "because of the content of their speech." But trial exhibits and testimonies also exposed a lack of preparation by Baton Rouge cops, particularly in using military-grade equipment. A BRPD representative admitted the department used a long-range acoustic device, a sonic weapon known to cause disorientation, even though it had never used it before not gave officers safety guidance. One officer said they were "messing around" with the weapon when they used it on protesters at close range, attorneys said. "What we didn't know until trial was the description that they were just 'messing around' with it," Most said. "That was quite significant testimony." BRPD's Failure to Reform Civil rights lawyers acknowledge that winning civil rights cases against law enforcement in Louisiana isn't easy. The state is located within the Fifth Circuit, where courts are among the most likely to accept assertions of qualified immunity, a doctrine that largely protects police officers from civil suits. In addition, Louisiana is one of only three states to have a one-year statute of limitations for bringing civil lawsuits challenging official misconduct in federal court. In building their case, attorneys in the Imani case took a deep dive into past actions by the BRPD that drew legal scrutiny. In 1961, the department arrested the leader of a group of Black students protesting racial discrimination and law enforcement policies. The man was peacefully standing on a sidewalk at the time of the arrest. That case, Cox v. Louisiana , ended in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1965 that the man's arrest violated his freedom of speech. "It is rare that you have as on-point a case from the U.S. Supreme Court about the city that you're contemplating suing," Most said. "We knew that there was a history that this particular department had, and so we followed up on those leads in our depositions." During their research, the plaintiffs' legal team discovered other examples of alleged BRDP misconduct that echoed their own claims. In 2005, for example, the complaint said that out-of-state officers from Michigan and New Mexico who'd volunteered to help police the city as its population surged were pulled out after they reported witnessing "egregious misconduct and potentially criminal actions by BRPD officers." "There was a complete failure of accountability," Most said. "Not a single officer was investigated for any conduct related to the protests — not the signing of false affidavits, not the forgery of officers signatures, not excessive force." Only one officer, Marcus Thompson, was investigated for "conduct unbecoming of an officer" by internal affairs for actions during the protest. His transgression was complaining to colleagues that BRPD was violating the protesters' constitutional rights, according to court documents. Three attorneys representing BRPD officers in the Imani case — Joseph K. Scott of Joseph K Scott III Attorney at Law, and parish attorneys Deelee Morris and David Lefeve — declined to comment. A spokesperson for the city did not respond to requests for comment. Emotional Testimony and Hard Facts Most and Adcock made no secret of it: They were nervous to take their case to a Louisiana jury. In the Fifth Circuit, questions over the application of qualified immunity often end up before juries — a strange situation given that it typically touches on highly technical aspects of the law that would be better reserved for judges, Most said. The challenge for plaintiffs' attorneys challenging police misconduct is to both present a compelling case to jurors and to give them enough information about the law to properly evaluate qualified immunity claims. Adcock said federal judges also walk a fine line in deciding either to reject a qualified immunity defense early on in a case — a move that allows defendants to appeal to the Fifth Circuit, effectively pausing a suit for as long as a year and a half — or allowing the claims to reach a jury. During the Imani trial, the plaintiffs each took the stand to share their experiences both during and after their arrests. Some jurors showed clear sympathy for the plaintiffs, their attorneys said. One of them openly cried while hearing the testimony of Nadia Salazar Sandi, a protester who recalled fearing she would be killed while in custody. According to the group's complaint, Salazar Sandi's hands turned purple as zip ties she was bound with when she was arrested cut off blood flow. But the plaintiffs' legal team made a deliberate choice to focus less on their clients' physical and psychological damages, which, although severe, could have been seen by jurors as exaggerated. Instead, the attorneys centered their case around the actions of the officers. "We made a decision to not minimize these injuries, but certainly to understate them, and focus on the behavior of the police," Adcock said. "I think that was one way that these jurors maybe just sympathized with the protesters." The plaintiffs are represented by William Most, David Lanser and Veronica Barnes of Most & Associates, and John Adcock of John Adcock Law LLC. The respondents are represented by Joseph K Scott III of Joseph K Scott III Attorney at Law LLC. The case is Imani et al. v. City of Baton Rouge et al., case number 3:17-cv-00439, in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed