|

Around two or three years ago, Keegan Caldwell's Boston-based law firm began receiving letters from incarcerated people from across the country. At first, he didn't read them. He was too busy growing his intellectual property boutique, Caldwell IP, into an established mid-sized firm. He knew the letters were in response to an Inc. Magazine article in which Caldwell opened up about his six felony convictions and his subsequent journey, against all odds, to becoming a lawyer. When he finally dug into the pile, Caldwell found a wide array of responses to his story. Some found it inspiring. Some, who were in prison for illegal patent licensing schemes, had business propositions for him. But one letter stood out in particular. It was from a man from Sanford, North Carolina, named Thomas Alston. He had been in federal prison since 2011 for money laundering, possession and conspiracy to distribute more than five kilograms of cocaine. He still had more than 17 years to go on his sentence when he contacted Caldwell. But Alston had an idea he needed help with. "Prior to that arrest, he had taken care of his grandmother for a number of years," Caldwell told Law360. "He was her primary caretaker, and there was a deep, genuine concern for his grandmother's welfare and health, and he used the resources that he had while being incarcerated to come up with an invention that allowed for people to make sure that their loved ones were taking their medicine while in a remote location." Alston's story resonated with Caldwell. He saw something in Alston that reminded Caldwell of a younger version of himself: a creative and entrepreneurial spirit with no place to channel that energy. "That's what really struck me," Caldwell said. "I was like, 'This is an entrepreneur.'" Caldwell began to help Alston secure a patent for his idea, and Alston's letter became the nexus for Caldwell IP's Incarcerated Innovator's Program. While many firms have taken on pro bono cases helping incarcerated or formerly incarcerated individuals overturn their convictions or seek shorter sentences, Caldwell's firm has taken a different approach to helping prisoners try to better their lives. The program helps inmates obtain and maintain patents for their ideas, whether to eventually start their own business or to try and monetize the idea through licensing deals. Caldwell is hoping the program will have an impact on recidivism. "One thing you can do, whether or not you're a convicted felon, is you can run a business," he said. "You can create a legitimate revenue stream for yourself by coming up with a decent business model." With a very unusual background for a law firm owner, Caldwell's efforts feel uniquely personal. In his early 20s, coming out of the U.S. Marine Corps, Caldwell struggled with addiction and racked up a hefty criminal record. Despite all this, he became a lawyer and a firm owner without ever setting foot in a law school. Over the years, there was a lot that people told Caldwell he couldn't do. "I feel like I have a unique perspective of knowing all those voices that people hear," he said. "People point you in the direction of something that is not going to be fulfilling because they don't think any of the other things are possible for you." So Caldwell's firm is spending time and money — in some cases upward of $100,000 for each person — on a handful of formerly or currently incarcerated people, to point them toward a brighter path forward, he said. "All of us at the firm just want to let people feel a little ray of hope that there's absolutely an opportunity for you," Caldwell said. "Don't listen to the naysayers. Just put one foot in front of the other and don't expect any miracles. And we're here to support you." Clearing a Path There's not much in the way of pro bono service in the intellectual property space, Caldwell said, likely because it can involve a big commitment of money and time. Securing and maintaining patents for clients can be a decadeslong process and can cost thousands of dollars. But Caldwell said that if his firm was going to help people this way, it needed to be in it for the long haul. "We're basically saying, for the right candidate, that we're all in," he said. "We're not going to just do this one little thing for you and then get out of here. We're with you. We're going to help figure out what your invention is, and we're going to help with everything." First, the firm helps provide a patent search, ensuring there aren't existing inventions that conflict with their client's idea. From there, Caldwell's team helps draft and submit the patent application, which includes several thousand dollars in fees to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Since the USPTO usually rejects most applications at first, he said, the firm commits to spending additional time and money fighting to reverse the initial decision. And then the firm continues to pay maintenance fees for 20 years while looking for licensing opportunities, which come with their own fees. The whole thing is expensive, but for Caldwell, it's worth it. "Our lives are filled with abundance that we're very grateful for, and it puts us in an opportunity to be able to help others [who] I think ... often get left behind, and there's no reason that they should," Caldwell said. Alston's first patent was approved in April 2022. Alston told Law360 during a recent call from a federal prison in Virginia that he read about Caldwell while his prison was on lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. Within a couple months, Caldwell wrote him back.

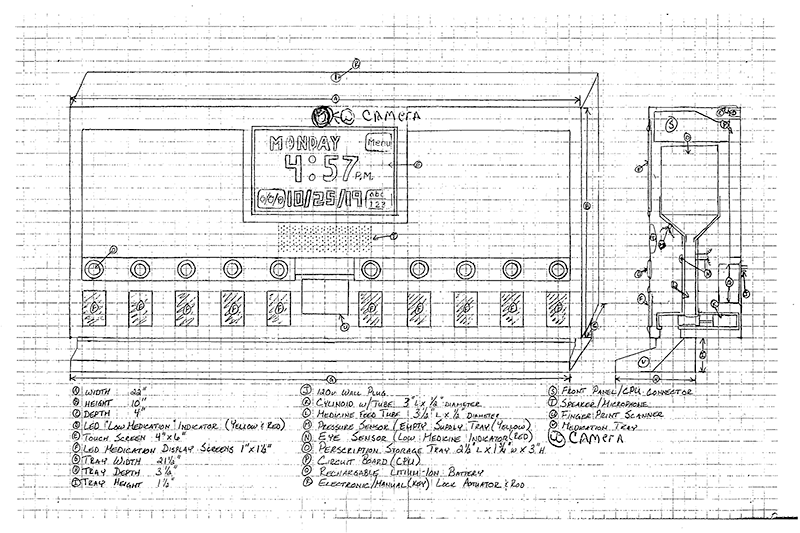

"He read about my case and knew I'd been in a long time, and he said, 'You deserve a second chance,'" Alston said. As he was trying to keep his mind occupied on the inside, Alston said he began drawing a design for an advanced pill dispenser that could be a solution to a problem he faced trying to help his grandmother navigate a breast cancer diagnosis that required her to take a variety of medications at certain times each day. Although his grandmother died in 2013, he thought the device he had concocted in his head could help others. "It's got everything on it," he said. "You can contact your doctor. We've got 10 slots for different types of medication. It'll tell you what the medication is for and what to do with it. You've got a camera on there too, so if you're in New York and your mother lives in Florida, you could check on her and make sure she takes her pills. If she didn't take her pills when the tray dispenses it at the time, it notifies you." Now that the patent is squared away, he said Caldwell and the firm's director of client relations, Bailey Domingo, have been helping him look for licensing deals. "I already kind of got it in my head ... how I want to do things with the proceeds I make off my inventions [if I get out]," Alston said. "I'll start small and then work my way up." Caldwell is also helping Bruce Bryan, who was released from a New York state prison on clemency in April, as Bryan files a patent application for a digital platform designed to help incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people pursue wrongful conviction claims by providing a database of all parties involved in previously overturned cases, including prosecutors, judges and public defenders. "So that in the future, if their names are ever mentioned in anything, we know to look closely at what they're doing because they have a history of doing this," Bryan said. Caldwell said he's hoping to help more people like Bryan, who have recently been released and want to achieve things despite all the setbacks that come with a criminal record and years behind bars. "He's this really charismatic, wonderful guy," Caldwell said of Bryan. "But when you've spent three decades of your life in a place like he has, there are a lot of social pressures you didn't have to deal with on a daily basis that quickly become a reality. I think it's the community's job to help these folks live a successful life." From Convict to Law Firm Owner Caldwell got his first felony conviction in 2002 for malicious destruction of property, after drunkenly tearing up a bar in Michigan as a 23-year-old. Over the next five years, he'd rack up another five felonies related to selling or possessing drugs, from marijuana to cocaine and heroin. "I was legit feral. I was not the same dude that you're talking to today," Caldwell told Law360. "I was like a street urchin. I knew how to steal Little Debbie's and sell crack. That's what I knew how to do. That was my life." Many with Caldwell's rap sheet would spend years inside a cell. He got lucky, though, and he was ultimately diverted to a drug treatment court and sent to a rehabilitation facility instead of a jailhouse. Newly sober in the mid-2000s, he was living in a men's shelter and meeting weekly with a social worker whom he eventually told he wanted to go to college. "They thought that was not a realistic thing for me," Caldwell said. "And I also didn't really think it was a realistic thing for me." But Caldwell did make it to college. Although he spent all of his freshman year still living in the men's shelter, Caldwell managed to complete his bachelor of science degree at Western Michigan University and continued on to get his doctorate in physical chemistry at The George Washington University. But he said that throughout his academic career, his criminal background weighed on him. "I lived in silence and loneliness, a little bit, with it," he said. "No one I got a Ph.D. with, not a single person, knew what was up with me, and I was terrified that they would find out. I figured they'd kick me out of school immediately." When Caldwell got out of school, he found his job options were limited to ones that didn't require a background check. Caldwell had always kind of wanted to be a lawyer, he said. Before his first conviction, however, he said he asked his public defender if they thought a legal career would still be possible despite Caldwell's blossoming criminal record. According to Caldwell, the lawyer told him, "Not if you're convicted of a felony." Yet Caldwell, several years and several degrees later, found himself working as a patent agent at a law firm. Because of his hard science background, he was able to take and pass the federal patent bar exam in 2014. He said that clearing the character fitness portion of the test was a life-changing achievement. "I was like, 'Oh my God.' Then I knew I was good. Not like a good person. I'm still terrible," he joked. "But there was a path. I knew when they gave me that licensure that I can actually do something with this now." After clearing the patent bar, which made him eligible to be a patent agent, not a lawyer, he worked with the intellectual property group at Downs Rachlin Martin PLLC from 2014 to 2016 before Caldwell went on to start his own law firm, Caldwell IP. It was only as he was working to get the firm up and running that Caldwell passed the Vermont State Bar exam, finally making him a real lawyer, without ever having gone to law school. Today, Caldwell IP boasts of more than 40 employees and offices in Boston; Los Angeles; Burlington, Vermont; and London. As the firm was growing at breakneck speed, however, Caldwell said there was still one obstacle to overcome: sharing his story. His criminal record was still something he kept quiet about. But when a magazine wanted to write a feature on his firm, he decided to open up. He said he was terrified that in sharing his criminal record, he'd lose out on clients, but the response was overwhelmingly positive. "I felt this huge weight lifted off my shoulders," Caldwell said. "I got some great PR out of it, which was nice, but then I think that it helped us as a firm too because everything [drove home the belief] that this stigma could be broken. We wouldn't be doing this program if not for me saying, 'Hey, you know, I'm a guy that was in the situation, and I was able to work on those things. And if you're in a situation like that, too, don't lose hope. Because there's hope for you too.'" Balancing Hope With Patience Alston said he knows making money off his intellectual property can be a long process. He knows he won't make money off his inventions right away. But being smack in the middle of a nearly three-decade sentence has taught him to wait. He was 42 years old and a career offender caught up in an illegal drug trafficking scheme when a North Carolina federal court put him away. He'll be 69 when he's released, although he submitted a federal application for clemency two years ago citing good behavior. Before he was incarcerated, Alston said he couldn't find any jobs in his hometown, so playing what he said was a small role in drug trafficking around the Texas/Mexico border was appealing. Caldwell said he can empathize. "Imagine that, in your neighborhood where you grew up, the most successful people that you knew, who took care of your community, were folks that were selling drugs," Caldwell said. Many people with a criminal history actually share a bent toward entrepreneurialism, Caldwell said. "Thomas, he built an enterprise," he said. "He knows what that is and now he has the tools to do that, and I think a lot of people have that skill set." Alston said he's working on a new project right now. He hopes he can make some money to give to his five grandchildren. He dreams of getting out and working in the real estate business, remodeling and flipping houses. "I've got a pretty creative mind," he said. "[Being a patent owner/inventor] has helped me use my mind in different ways now, so that I can do something positive."

1 Comment

Sheeraz Khan

11/27/2023 05:00:20 pm

Your post emphasizes the importance of Make Money online.For more details,<a href="https://www.toprevenuegate.com/pdaz9utx?key=45314bcc51ea880e1cb0374d19019638" target="_blank">Click here</a>.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed