|

A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court on Friday ruled that a corporation's failure to disclose certain information about its future business risks, absent any affirmative statement that would make such silence misleading, cannot itself be the basis of a private securities fraud claim.The court vacated and remanded a Second Circuit decision in favor of Macquarie Infrastructure Corp. shareholder Moab Partners LP. Moab accused Macquarie of misleading investors by remaining silent about the impact that a soon-to-be-implemented global ban on high-sulfur fuels would have on its oil storage business. The investor said the company committed fraud under U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Rule 10b–5(b) by remaining silent on the issue. But a "duty to disclose ... does not automatically render silence misleading under Rule 10b–5(b)," the high court reasoned in an opinion authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Instead, management's failure to disclose trends or uncertainties that could harm their business can support a claim "only if the omission renders affirmative statements made misleading," the court said.Salvatore Graziano of Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossmann LLP, one of the lawyers representing Moab Partners, told Law360 on Friday that the Supreme Court's decision was not the end of the road for his client. "There is going to be no impact on our case, because the Supreme Court has given us a road map to plead a half-truth, which we have," Graziano said, pointing to statements made in 2015 and 2016 that he said made it appear as if demand for the stored products was not decreasing. He also said the proposed class of investors will continue to push securities fraud claims under separate provisions of Rule 10b–5(b) that the high court did not rule on, as well as under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. Linda Coberly of Winston & Strawn LLP, one of the attorneys representing Macquarie, said she was thrilled with the justices' decision. "It provides critical guidance to companies, litigants and judges, for our case and beyond," she said. "Our case will now move forward with this important clarification in the law." The lawsuit was filed in 2018 and accuses Macquarie of failing to warn investors that the company's most profitable segment stood to lose a significant amount of fuel storage business once an international fuel standard known as IMO 2020 went into effect. The regulation was adopted in 2016, four years before going into effect, but shareholders allege that Macquarie waited two years before publicly announcing a drop-off in customers due to the decline in fuel sales. The announcement led the stock price to drop 41%, according to Friday's Supreme Court opinion. Macquarie won dismissal of the case at the district court, which ruled that Moab Partners had not alleged that the company made any actionable half-truths about its reliance on the regulated fuel oil. The Second Circuit revived the case, saying that corporations have a duty not to omit material information. The company argued that a split still lingered between the Second Circuit and other circuit courts over the applicable standard of disclosure under Item 303, which requires management to discuss trends or uncertainties facing the company. The high court initially planned to address the split in 2017 through a case brought by Leidos Inc., but that case settled before the court could hear oral arguments or issue an opinion. Any broader impact on securities litigation from Friday's ruling will be limited, Graziano said, since companies can still be sued by the SEC for outright omitting necessary information from Item 303 statements. The SEC weighed in on the Supreme Court case in favor of Moab Partners, telling the court that investors rely on a company's MD&A disclosures to understand a company's financial risks and that allowing companies to omit those risks "would allow unscrupulous parties to exploit the very trust that disclosure requirements are designed to foster." The agency didn't immediately respond to a request for comment. Macquarie is represented by John E. Schreiber, Kerry C. Donovan, Lauren Gailey and Linda Coberly of Winston & Strawn LLP, as well as by Richard W. Reinthaler. Moab Partners is represented by Salvatore J. Graziano, Lauren Amy Ormsbee, Jesse L. Jensen and William E. Freeland of Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossmann LLP, David C. Frederick, Joshua D. Branson and Dustin G. Graber of Kellogg Hansen Todd Figel & Frederick PLLC, and Lori Marks-Esterman and John G. Moon of Olshan Frome Wolosky LLP. The government is represented by Megan Barbero, Michael A. Conley, Jeffrey A. Berger and Rachel M. McKenzie of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and Elizabeth B. Prelogar, Malcolm L. Stewart and Ephraim A. McDowell of the U.S. Department of Justice. The case is Macquarie Infrastructure Corp. et al. v. Moab Partners LP et al., case number 22-1165, in the Supreme Court of the United States.

0 Comments

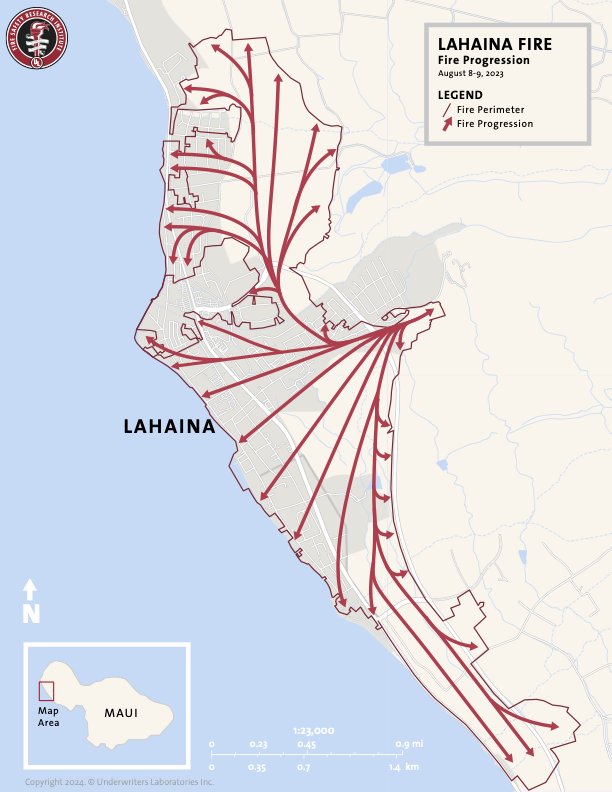

Hawaii's attorney general on Wednesday released findings from the first report of a three-part investigation into how state and county governments responded to the wildfires that ignited on the island of Maui last year, decimating the historic town of Lahaina and leaving more than 100 people dead. The first report, prepared by the fire safety arm of UL Research Institutes, provides a minute-by-minute timeline of how the fire spread between 2:55 p.m. HST on Aug. 8 to 8:30 a.m. HST on Aug. 9, and will be used to analyze how various fire protection systems worked and provide recommendations for how to prevent another such disaster, Attorney General Anne Lopez said. "Responsible governance requires we look at what happened, and using an objective, science-based approach, identify how state and county governments responded," Lopez said in a statement Wednesday. "We will review what worked and what did not work, and make improvements to prevent future disasters of this magnitude." As part of its investigation, UL's Fire Safety Research Institute collected radio communication logs and transmissions from Maui County 911 calls, the Maui Fire Department, the Maui Police Department and MPD Dispatch, as well as Hawaiian Electric dispatch communications, according to the report. Investigators also made site visits from late August through January, including surveying the area by helicopter and capturing aerial imagery of all burned and adjacent unburned areas, the report states. The report includes a map showing the fire's progression on its path of destruction through Lahaina, on the northwest coast of the island. Steve Kerber, vice president and executive director of FSRI, said in a statement Wednesday that the report and timeline focused on several factors, including preparedness efforts, the weather and its impact on infrastructure, and other fires occurring on Maui during that same time period. "The Lahaina wildfire tragedy serves as a sobering reminder that the threat of grassland fires, wildfires and wildfire-initiated urban conflagrations, fueled by climate change and urban encroachment into wildland areas, is a reality that must be addressed with the utmost urgency and diligence — not just in Hawai'i," Kerber said. But he cautioned that conclusions should not be drawn solely from this initial report and timeline, noting that this data will be used to dig deeper into how fire protection systems functioned and what can be done to improve safety in the future. Lopez added, "This is not a report about the 'cause' of any fire — the causation investigation is being performed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and the Maui Fire and Public Safety Department." Hawaiian Electric Co., which is under scrutiny for its alleged role in sparking the devastating Lahaina wildfire, is embarking on its own investigation to determine the cause of the blaze, but said in September that it could take up to 18 months to have an answer. Litigation has also been launched in the wake of the fire, including a derivative suit filed last week by a Hawaiian Electric Industries Inc. shareholder alleging the company's executives and directors knew that it was not prepared for the wildfire, which the suit says caused reputational and financial damage to the company. That suit followed an earlier shareholder class action in August blaming the company for the massive downturn in its stock price following the fire after it allegedly spent years ignoring warnings that it lacked the safety protocols to address wildfires. Pomerantz LLP was selected in December to serve as lead counsel in the suit. Just after the fire, Maui County filed suit seeking to hold Hawaiian Electric accountable for the billions of dollars in damages to public property caused by the Lahaina fire and the Kula fire, which ignited around 11:30 a.m. HST on Aug. 8, alleging that the company's downed power lines sparked the blazes. The first report, prepared by the fire safety arm of UL Research Institutes, provides a minute-by-minute timeline of how the fire spread between 2:55 p.m. HST on Aug. 8 to 8:30 a.m. HST on Aug. 9, and will be used to analyze how various fire protection systems worked and provide recommendations for how to prevent another such disaster, Attorney General Anne Lopez said. "Responsible governance requires we look at what happened, and using an objective, science-based approach, identify how state and county governments responded," Lopez said in a statement Wednesday. "We will review what worked and what did not work, and make improvements to prevent future disasters of this magnitude." As part of its investigation, UL's Fire Safety Research Institute collected radio communication logs and transmissions from Maui County 911 calls, the Maui Fire Department, the Maui Police Department and MPD Dispatch, as well as Hawaiian Electric dispatch communications, according to the report. Investigators also made site visits from late August through January, including surveying the area by helicopter and capturing aerial imagery of all burned and adjacent unburned areas, the report states. The report includes a map showing the fire's progression on its path of destruction through Lahaina, on the northwest coast of the island. Steve Kerber, vice president and executive director of FSRI, said in a statement Wednesday that the report and timeline focused on several factors, including preparedness efforts, the weather and its impact on infrastructure, and other fires occurring on Maui during that same time period. "The Lahaina wildfire tragedy serves as a sobering reminder that the threat of grassland fires, wildfires and wildfire-initiated urban conflagrations, fueled by climate change and urban encroachment into wildland areas, is a reality that must be addressed with the utmost urgency and diligence — not just in Hawai'i," Kerber said. But he cautioned that conclusions should not be drawn solely from this initial report and timeline, noting that this data will be used to dig deeper into how fire protection systems functioned and what can be done to improve safety in the future. Lopez added, "This is not a report about the 'cause' of any fire — the causation investigation is being performed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and the Maui Fire and Public Safety Department." Hawaiian Electric Co., which is under scrutiny for its alleged role in sparking the devastating Lahaina wildfire, is embarking on its own investigation to determine the cause of the blaze, but said in September that it could take up to 18 months to have an answer. Litigation has also been launched in the wake of the fire, including a derivative suit filed last week by a Hawaiian Electric Industries Inc. shareholder alleging the company's executives and directors knew that it was not prepared for the wildfire, which the suit says caused reputational and financial damage to the company. That suit followed an earlier shareholder class action in August blaming the company for the massive downturn in its stock price following the fire after it allegedly spent years ignoring warnings that it lacked the safety protocols to address wildfires. Pomerantz LLP was selected in December to serve as lead counsel in the suit. Just after the fire, Maui County filed suit seeking to hold Hawaiian Electric accountable for the billions of dollars in damages to public property caused by the Lahaina fire and the Kula fire, which ignited around 11:30 a.m. HST on Aug. 8, alleging that the company's downed power lines sparked the blazes. U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff released scathing findings from a federal probe into Georgia’s child welfare system on Tuesday, which concluded that systemic failures and mismanagement within the agency contributed to the deaths of children. The Senate Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on Human Rights and the Law, chaired by Ossoff, conducted the inquiry. It was announced more than a year ago and prompted by an investigation in late 2022 by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The report describes how the Division of Family & Children Services (DFCS) has identified “significant shortcomings” like staffing shortages, and insufficient training, that contribute to death and serious injuries among children it is responsible for. The subcommittee reviewed years of audits and found an internal audit from the child welfare agency showing the state failed to properly assess risks and safety concerns in 84% of cases that were reviewed. “Those audits reveal that DFCS consistently fails to adequately assess and address the safety risk and safety concerns relating to children,” the report said. The 64-page report detailed several cases of child deaths in which they said DFCS mismanaged their care. A spokesperson for the Department of Human Services, which oversees DFCS, sent an 11-page response to Ossoff’s report, taking issue with many of the findings. The spokesperson said the subcommittee’s report omits DFCS’s improvements, like addressing the issue of housing children in hotels, and strengthening safeguards for children in its care. “The subcommittee’s report omits key context, ignores relevant data that undermine the report’s primary assertions, and takes great lengths to misrepresent DFCS actions, facts about various cases, and outcomes for many children in the state’s care,” a DHS spokesperson said in a statement issued minutes before Ossoff’s report became public. “Our staff and leadership take our responsibility to Georgia’s at-risk youth with the utmost seriousness and will continue to identify and implement solutions that better serve those in our care. We encourage Sen. Ossoff to focus his efforts on putting the welfare of children above political gamesmanship.” The Senate subcommittee said it reviewed thousands of pages of non-public documents from the Department of Human Services, which oversees the child welfare system in Georgia, and from the state’s child welfare watchdog, known as the Office of the Child Advocate. It also interviewed more than 100 witnesses, including top officials like DHS Commissioner Candice Broce, and convened four public hearings. Among child deaths cited in the report, it says DFCS received a police report in May 2023 describing a mother wandering outside with her year-old baby, in “an obvious state of delusion and distress.” A DFCS worker tried and failed to contact the family prior to the child’s death two days later. The state’s ombudsman told the subcommittee that “they did not believe DFCS responded with appropriate urgency in light of the seriousness of the allegations.” In its response, DHS said Ossoff’s report falsely claims that DFCS failed to keep children safe from physical and sexual abuse, and that those failures contributed to the deaths of children. “These allegations are unfounded and irresponsible,” DHS said in a response. “The report relies on various reviews and audits conducted by DFCS itself. Those reviews, however, do not support the report’s conclusions.” DHS also noted that the report was written by majority staff while Ossoff’s initial letter was bipartisan. In 2022, the Atlanta Journal Coonstitution conducted a months-long review of DFCS, obtaining hundreds of pages of public documents and speaking with experts who described a child welfare system in turmoil. Caseworkers at DFCS were leaving their jobs in droves, fueled by low pay, frustration with leadership, and exhaustion from increased workloads, according to state human resources reports. Also in 2022, the office of the state’s ombudsman for child welfare alleged breakdowns within DFCS, identifying 15 systemic issues. The ombudsman’s office said workers were no longer adequately responding to child abuse cases, and that the murder of a 4-year-old boy was a consequence of systemic failures. State officials vehemently disagreed with the assessment, saying the ombudsman failed to provide any evidence backing up its claim of systemic failures within DFCS that leave children in danger. According to an internal review of the 4-year-old’s death conducted by the state, there was “disturbing” mismanagement in the case, but state officials found his death was an isolated tragedy. The report released by Ossoff found the subcommittee’s investigation validated the ombudsman’s earlier report of DFCS’ “systemic” failures to keep children safe from physical and sexual abuse. The report also says that DHS’ Office of the Inspector General conducted an “inadequate, limited-scope review,” which it alleges was “potentially jeopardized” by interference from DHS Commissioner Broce. The subcommittee says it found a number of issues within the DHS review, including that the inspector general failed to conduct critical interviews, never reviewed key evidence submitted to DHS, and never reviewed audits and reports that would have corroborated the ombudsman’s findings. DHS, in its response, said the Senate subcommittee’s report “confuses and misuses statistics” DFCS has reported to the federal government, and “wrongly denigrates” the work of the DHS Office of the Inspector General and other personnel. DHS also said that “at no time did the Commissioner direct the investigation or ask for a particular outcome.” Additionally, the subcommittee says it obtained documentation from the state’s ombudsman, describing examples in which DFCS failed to protect children from sexual abuse. For example, an earlier audit of the Glynn County DFCS Office found a child was raped by an adult resident of their group home, after DFCS declined to open an investigation. The state’s ombudsman reported that the child was raped again after that. The report also said that DHS is “weakening independent oversight” of Georgia’s child welfare system by taking over the selection of members oversight bodies, or “Citizen Review Panels,” that are tasked with reviewing DFCS’ performance. These panels have been appointed by an independent entity for the last 16 years, according to the report, and during that time have been “sharply critical” of DFCS’ performance. DHS announced that it will now appoint members of these panels, according to the report. Previously, lawyers for the DFCS sent a letter to Ossoff, calling the Senate investigation a “political” endeavor. Broce, the DHS commissioner, is a close ally of Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, who could challenge Ossoff when he runs for re-election in 2026. Office of the Child Advocate Director Jerry Bruce, who serves as the ombudsman, did not respond to a request for comment. DHS, in its response, said the Senate subcommittee’s report “confuses and misuses statistics” DFCS has reported to the federal government, and “wrongly denigrates” the work of the DHS Office of the Inspector General and other personnel. DHS also said that “at no time did the Commissioner direct the investigation or ask for a particular outcome.” Additionally, the subcommittee says it obtained documentation from the state’s ombudsman, describing examples in which DFCS failed to protect children from sexual abuse. For example, an earlier audit of the Glynn County DFCS Office found a child was raped by an adult resident of their group home, after DFCS declined to open an investigation. The state’s ombudsman reported that the child was raped again after that. The report also said that DHS is “weakening independent oversight” of Georgia’s child welfare system by taking over the selection of members oversight bodies, or “Citizen Review Panels,” that are tasked with reviewing DFCS’ performance. These panels have been appointed by an independent entity for the last 16 years, according to the report, and during that time have been “sharply critical” of DFCS’ performance. DHS announced that it will now appoint members of these panels, according to the report. Previously, lawyers for the DFCS sent a letter to Ossoff, calling the Senate investigation a “political” endeavor. Broce, the DHS commissioner, is a close ally of Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, who could challenge Ossoff when he runs for re-election in 2026. Office of the Child Advocate Director Jerry Bruce, who serves as the ombudsman, did not respond to a request for comment. US District Courts applying Doe and Hubbell have reached different conclusions on biometric unlocking. The 9th Circuit decided that the compelled use of Payne's thumb "required no cognitive exertion" because it "merely provided CHP with access to a source of potential information, much like the consent directive in Doe. The considerations regarding existence, control, and authentication that were present in Hubbell are absent or, at a minimum, significantly less compelling in this case. Accordingly, under the current binding Supreme Court framework, the use of Payne's thumb to unlock his phone was not a testimonial act and the Fifth Amendment does not apply."

The 9th Circuit panel said its "opinion should not be read to extend to all instances where a biometric is used to unlock an electronic device," as "Fifth Amendment questions like this one are highly fact dependent and the line between what is testimonial and what is not is particularly fine." "Indeed, the outcome on the testimonial prong may have been different had Officer Coddington required Payne to independently select the finger that he placed on the phone," the ruling said. "And if that were the case, we may have had to grapple with the so-called foregone conclusion doctrine. We mention these possibilities not to opine on the right result in those future cases, but only to demonstrate the complex nature of the inquiry." Foregone conclusion doctrine The foregone conclusion doctrine noted above generally "applies if the government can show it knows the location, existence, and authenticity of the purported evidence with reasonable particularity," according to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. "Even if the act of decryption is potentially testimonial, it may not violate the Fifth Amendment if the implicit facts conveyed by doing so would be a 'foregone conclusion' that 'adds little or nothing to the sum total of the government's information,'" the lawyers' group explains in a primer on compelled decryption. Yesterday's ruling from the 9th Circuit also rejected Payne's argument that California Highway Patrol violated his Fourth Amendment rights. The Fourth Amendment dispute involved a special search condition in Payne's parole "requiring him to surrender any electronic device and provide a pass key or code, but not requiring him to provide a biometric identifier to unlock the device," the ruling said. Despite that parole condition, "the search was authorized under a general search condition, mandated by California law, allowing the suspicionless search of any property under Payne's control," the ruling said. "Moreover, we hold that any ambiguity created by the inclusion of the special condition, when factored into the totality of the circumstances, did not increase Payne's expectation of privacy in his cell phone to render the search unreasonable under the Fourth Amendment," the panel wrote. The U.S. Army, the country’s largest military branch, will no longer allow military commanders to decide on their own whether soldiers accused of certain serious crimes can leave the service rather than go on trial.

The decision comes one year after ProPublica, The Texas Tribune and Military Times published an investigation exposing how hundreds of soldiers charged with violent crimes were administratively discharged instead of facing a court martial. Under the new rule, which goes into effect Saturday, military commanders will no longer have the sole authority to grant a soldier’s request for what is known as a discharge in lieu of court martial, or Chapter 10, in certain cases. Instead, the newly created Office of Special Trial Counsel, a group of military attorneys who specialize in handling cases involving violent crimes, must also approve the decision. Without the attorneys’ approval, charges against a soldier can’t be dismissed. The Office of Special Trial Counsel will have the final say, the Army told the news organizations. The new rule will apply only to cases that fall under the purview of the Office of Special Trial Counsel, including sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse, kidnapping and murder. In 2021, Congress authorized creation of the new legal office — one for each military branch except the U.S. Coast Guard — in response to yearslong pressure to change how the military responds to violent crimes, specifically sexual assault, and reduce commanders’ control over that process. As of December, attorneys with this special office, and not commanders, now decide whether to prosecute cases related to those serious offenses. Army officials told the news organizations that the change in discharge authority was made in response to the creation of the Office of Special Trial Counsel. As far back as 1978, a federal watchdog agency called for the U.S. Department of Defense to end its policy of allowing service members accused of crimes to leave the military to avoid going to court. Armed forces leaders continued the practice anyway. Last year, ProPublica, the Tribune and Military Times found that more than half of the 900 soldiers who were allowed to leave the Army in the previous decade rather than go to trial had been accused of violent crimes, including sexual assault and domestic violence, according to an analysis of roughly 8,000 Army courts-martial cases that reached arraignment. These soldiers had to acknowledge that they committed an offense that could be punishable under military law but did not have to admit guilt to a specific crime or face any other consequences that can come with a conviction, like registering as a sex offender. The Army did not dispute the news organizations’ findings that the discharges in lieu of trial, also known as separations, were increasingly being used for violent crimes. An Army official said separations are a good alternative if commanders believe wrongdoing occurred but don’t have the evidence for a conviction, or if a victim prefers not to pursue a case. Military law experts contacted by the news organizations called the Army’s change a step in the right direction. “It’s good to see the Army has closed the loophole,” said former Air Force chief prosecutor Col. Don Christensen, who is now in private practice. However, the Office of Special Trial Counsel’s decisions are not absolute. If the attorneys want to drop a charge, the commander still has the option to impose a range of other administrative punishments, Army officials said.Christensen said he believes commanders should be removed from the judicial process entirely, a shift he said that the military has continued to fight. Commanders often have little to no legal experience. The military has long maintained that commanders are an important part of its justice system.Christensen said he believes commanders should be removed from the judicial process entirely, a shift he said that the military has continued to fight. Commanders often have little to no legal experience. The military has long maintained that commanders are an important part of its justice system. “They just can’t break away from commanders making these decisions,” said Christensen, who’s been a vocal critic of commanders’ outsize role in the military justice system. “They’re too wedded to that process.” The Army told the newsrooms that additional changes to DOD and Army policy would be required to remove commanders entirely and instead give the Office of Special Trial Counsel full authority over separations in lieu of trial. The news organizations reached out to several military branches to determine how the creation of the Office of Special Trial Counsel will affect their discharge processes. The U.S. Navy has taken steps similar to the Army’s. In the U.S. Air Force, the Office of Special Trial Counsel now makes recommendations in cases involving officers, and the branch is in the process of changing the rules for enlisted members. The U.S. Marines confirmed to the news organizations that it has not yet changed its discharge system. “They just can’t break away from commanders making these decisions,” said Christensen, who’s been a vocal critic of commanders’ outsize role in the military justice system. “They’re too wedded to that process.” The Army told the newsrooms that additional changes to DOD and Army policy would be required to remove commanders entirely and instead give the Office of Special Trial Counsel full authority over separations in lieu of trial. The news organizations reached out to several military branches to determine how the creation of the Office of Special Trial Counsel will affect their discharge processes. The U.S. Navy has taken steps similar to the Army’s. In the U.S. Air Force, the Office of Special Trial Counsel now makes recommendations in cases involving officers, and the branch is in the process of changing the rules for enlisted members. The U.S. Marines confirmed to the news organizations that it has not yet changed its discharge system. Forty-five states have now completed climate action plans outlining how they'll advance federal climate goals through policy and programs in coming years, with most focusing at least in part on real estate development as a way to reduce emissions.

Many of the states — as well close to a dozen major metro areas — will focus on real estate development policy such as upzoning, committing to building weatherization and electrification, conservation, and renewable energy development, among other common goals. Submitting a "priority action climate plan" was a prerequisite for eligibility for $4.6 billion in grants under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Climate Pollution Reduction Grants program to carry out the policies and programs in the recent action plans. Those grant awardees will be announced in coming months. The states were required to outline priority measures that could be customized to meet local goals and challenges, but which must take into account low-income and disadvantaged communities and be implementation-ready. While many of the states' priority measures are dependent on funding to begin implementation, the action plans still give insight into the direction each state is moving in its climate-related real estate regulation. Florida, Iowa, Kentucky, South Dakota and Wyoming did not submit reports. Here, Law360 takes a look at the real estate and development-related measures each participating state is prioritizing in its climate action plans. Alabama Many of Alabama's land-related priorities surrounded agriculture and offsetting greenhouse gas emissions from farming and transportation of food and other resources. The state is proposing implementing solar arrays on farms to reduce agriculture's high energy consumption and boost resilience, as well as to lessen the climate impact of irrigation. The report also proposes programs and measures to increase local production of grains and vegetables to reduce the emissions generated in transporting those commodities from the Midwest and California. Alabama officials would develop a list of potential farms and awardees to benefit from the solar and irrigation projects, as well as a list of potential contractors to carry out the work. The state has also committed to creating incentive programs for energy efficiency retrofits in commercial and industrial buildings including heating, ventilation and cooking appliances. In the residential sector, the state is are also eyeing the same energy efficiency retrofit programs in addition to programs to weatherize buildings through insulation, new windows and doors, and efficient water heating. Alaska Alaska has had a Weatherization Assistance Program since the 1990s but is proposing to expand funding for the program to allow additional homes to be weatherized. The state is seeking further weatherization and energy efficiency measures for public buildings like schools, universities and state and city/tribal office buildings. Alaska officials are also looking to significantly expand the Alaska Energy Authority-owned Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project, which diverts water from the Dixon Glacier through a canal and a 5-mile underground tunnel into Bradley Lake and ultimately to an electric grid that serves 75% of the state's population. To complete the project, the state would need $342 million. It currently has $7.36 million committed. The Alaska Energy Authority is also proposing a residential rooftop solar program catering to low-income and disadvantaged households. Arizona Arizona officials are looking to launch a program called Whole Home Health/Clean Green Affordable Homes, which will fund upgrades like wiring, mold remediation, fire safety and residential energy efficiency upgrades. Part of the program would include home energy audits, and funding would expand access to weatherization, efficiency upgrades and electrification. Another measure would urge municipalities to upgrade their building codes. Because Arizona is a home-rule state, that initiative would need to come from the municipalities, but the state would plan to use grants to incentivize building code updates to the latest energy efficiency standards. A grant program, if funded, would give communities, multifamily housing owners and homeowners grants to install solar-plus-battery systems in residential and community buildings to increase electricity excess and support resilience in power outage and poor grid areas. Arkansas Arkansas is investigating the development of community-scale renewable energy generation and storage, city and municipal solar development, and energy efficiency appliance measures to state programs. Arkansas' goals of incentivizing and funding energy efficiency upgrades in buildings focuses largely on schools, prioritizing building enveloping — which consists of upgrading doors, windows and insulation — renewable energy generation, updated lighting and weatherization. California California's priority measures are largely focused on transportation, natural land and agriculture, with few building-centric proposals. The state is proposing to expand the Energy Conservation Assistance Act to scale 0% and 1% interest loans to educational institutions, municipalities and tribal nations for clean energy generation, energy storage, electric vehicle infrastructure and energy efficient upgrades. Expanding the Self-Generation Incentive Program would allow for more "behind-the-meter" energy storage, the state said, and it would enhance resilience during power outages. California is proposing to upgrade low-income homes with energy efficiency measures and replace fossil fuel equipment like water heaters, space heating and cooling, and cooktops with electric versions at low or no cost to residents in single-family, multifamily and mobile homes. Colorado In 2022, Colorado enacted its Energy Performance for Buildings law, which requires commercial, multifamily and public buildings over 50,000 square feet to report annual energy use and reduce it incrementally over the next decade. The state's climate action plan would seek federal funding to develop reporting data and model ordinances to further implement the new law and to bring technical assistance to large commercial buildings in developing case studies and sourcing low-interest financing. The state is also working to prioritize transportation infrastructure and pedestrian and bike connectivity to lower emissions from vehicle traffic, and to introduce parking reduction measures like building less parking and using paid parking. The funding would also be used to adopt the 2021 energy code earlier than planned, and to write building code to encourage solar- and EV-ready housing production, including incentives for local governments that update those standards. Colorado would encourage accessory dwelling units by right wherever single family homes are allowed, and eliminate occupancy limits in an effort to increase density and therefore lower emissions from urban sprawl and transportation. Measures would be implemented to encourage transit-oriented multifamily development by, for example, reducing or eliminating fees and launching infrastructure or density bonus incentives. Office-to-residential conversions or other adaptive reuse policies are also highlighted, as well as potential policies to discourage greenfield development. Connecticut According to its climate action plan, Connecticut would implement policies and programs to increase adoption of heat pumps statewide, expand funding for energy efficiency programs and weatherization. The state would also incentivize installation of EV-charging infrastructure near multifamily homes and other areas with few current EV-charging options. Delaware Delaware plans to increase on-site renewable energy systems in commercial and residential buildings by expanding existing state programs, and to prepare the state for offshore wind energy opportunities. The state's building energy codes would be strengthened, and energy efficiency opportunities for low- and moderate-income residents would be expanded, as would the state's Energy Efficiency Investment Fund, which incentivizes nonresidential, commercial and industrial buildings to complete efficiency upgrades. Officials also plan to expand EV-charging infrastructure, prioritize urban greenspaces and permanently protect 2,500 acres of forest area by 2028 through conservation. District of Columbia Federal funding would support buildings under 10,000 square feet in low-income and disadvantaged communities to upgrade systems and reduce emissions. The district would implement policies prioritizing rehabilitation of existing housing stock to meet updated codes and energy standards. Possible policies could include requiring asset and energy use disclosure at the time of sale or lease, requiring energy audits and upgrades at the time of sale, and expanding weatherization and home efficiency assistance. Officials highlight policies of requiring new construction design to account for climate risk, developing construction codes encouraging resilient design, providing technical assistance and incentivizing passive heating and cooling with an ultimate goal to adopt fossil fuel-free construction codes by 2026. Georgia Georgia is seeking to implement weatherization for residential buildings, home energy rebates for purchasing electric and energy efficient appliances and systems, and energy efficiency lighting upgrades in commercial buildings. New policies would increase renewable energy — especially solar — through rooftop installation on government-owned buildings, community solar, and renewables at industrial facilities. The state would launch a program for farmland conservation and to implement green farming practices, reduced-till farming and cover cropping. Hawaii Federal funding could accelerate a transportation infrastructure measure called Skyline Connect to improve connection between Skyline rail and the bus on O'ahu, which, coupled with another measure to improve "complete streets," would make pedestrian and bike modes of travel more accessible. The city of Honolulu is collaborating with counties, the state and a utility commission to create a statewide affordable housing retrofit program to increase energy efficiency in multifamily buildings. The state also has a goal to plant 1 million native trees in Maui County to restore forest land, with the intention of alleviating threats like flood and fire. Idaho If funded, Idaho would expand existing energy efficiency systems like weatherization, lighting retrofits, appliances and heating and cooling systems. The state wants to implement a measure to support conservation and streamline the pathway to conservation easements for existing land acquisition programs, and to develop a program to support solar adoption. Illinois Illinois seeks to fill in funding gaps in existing federal and state framework that hinder energy efficiency and building electrification efforts, to provide technical assistance and to implement low-carbon and energy-focused building codes. The state would create a whole-home decarbonization incentive of up to $12,000 per household, the Illinois Climate Bank would launch low-cost financing for decarbonization incentives, and a lease-to-own structure for system installations would be implemented. Funding would allow for the development of a contractor portal to share information across agencies, manage low-cost and easy-to-access loans and working capital, and streamline application processes. Additionally, owners of large buildings could connect to decarbonization and retrofitting resources through a "clean buildings concierge" service. The state is working to finalize its new Stretch Energy Code and create grants for local governments to adopt the framework. Finally, the state will eye new and scalable models of interconnected community-scale geothermal networks that allow residents and businesses to opt in to connect to the shared geothermal ground loop to heat and cool buildings. Indiana Indiana would implement programs to retrofit and weatherize buildings and to adopt energy efficient building practices like increasing insulation, building envelope upgrades, improving heating and cooling systems and upgrading lighting and passive heating. The state would focus on zoning and development code updates to diversify and improve land use, create bike and pedestrian infrastructure, improve public transit and change traffic patterns to make vehicle travel more efficient. Kansas Kansas would expand the state's existing weatherization assistance program to improve heating and cooling, upgrade insulation, improve air sealing, and replace doors and windows. It also seeks to increase solar, wind and other renewable energy production statewide. Louisiana Louisiana is prioritizing a "one-stop shop" for building owners to find state, local and federal incentives and grants for projects like weatherization, roof repairs and solar. Policies would prioritize energy efficient upgrades that improve resilience like heating and cooling, ventilation and shelter during and after natural disasters. The state would also implement a program to incentivize facility audits and comprehensive retrofit evaluations for multifamily, commercial and industrial buildings. It would also simplify local permitting to conduct those retrofits. Louisiana doesn't currently have any community solar projects in place nor any regulations, so the state would develop loan products that allow local government-led community solar projects and incentivize community solar, particularly for low-income households. Maine Maine already has a climate action framework called Maine Won't Wait, including goals to install at least 100,000 heat pumps in buildings by 2025, implementing upgraded appliance standards, weatherizing at least 35,000 homes and businesses by 2030, and developing building codes to align with climate goals. With a goal of 80% of electricity usage coming from renewables by 2030, federal funding would accelerate the current climate plan efforts and allow the state to craft policy for offshore wind, distributed energy and energy storage. The state would also develop land use regulations and laws specific to resilience for flooding and other climate impacts. Maryland Maryland's building energy upgrades focus on new zero-emission heating systems, and starting in 2024, the state will offer rebates up to $8,000 for the cost of heat pump installation in some low-, moderate- and middle-income homes. The state will adopt the latest energy code, according to its climate plan, and as of October 2023, EV-charging equipment will need to be installed during the construction of single-family homes, duplexes and townhouses. The EV-charging regulation could soon be extended to multifamily housing under the climate plan, depending on a yet-to-be-completed cost-barrier analysis. If that analysis is positive, the document calls for the legislature to introduce EV-ready verbiage for new multifamily buildings, along with solar-ready standards. Massachusetts Massachusetts aims to craft policies that assist local governments and residential and commercial building owners with energy efficiency analyses and with implementing renovations or retrofits to increase efficiency. The state intends to increase heat pump adoption, expand geothermal adoption, accelerate offshore wind infrastructure and solar development with a focus on community-scale solar. Michigan Aiming to reduce heat-related emissions in homes and businesses by 17% by 2030, Michigan plans to use federal funding to build on current state programs like Energy Waste Reduction and Sacred Spaces Clean Energy Grants. The state would focus on stronger requirements, incentives and financing options for energy efficiency and energy waste reduction, and adopting electrification as an alternative heat source. Upgrading transit infrastructure and expanding EV-charging infrastructure were also highlighted priorities. Minnesota Minnesota is eyeing a slew of voluntary incentives, programs and rebates to decarbonize residential buildings through electrification, renewable energy implementation, upgraded systems like heating and cooling, and service panel upgrades. The state would focus on the same measures for commercial buildings, but offer grants, loans and tax rebates and credits as the incentives. A potential policy highlighted in the report includes designing new buildings using green building principles, energy sources, materials and techniques. Mississippi Mississippi hopes to use existing technology to expand small-scale solar in residential and commercial buildings. The state would also incentivize building envelope upgrades like exterior walls, foundations, roofs, windows and doors to control heat, light and noise. It also wants to expand programs that incentivize upgrading lighting, HVAC, water heating, appliances and power systems in both commercial and residential buildings. Missouri Much of Missouri's action plan focuses on real estate upgrades, and the state is proposing weatherization upgrades and building electrification through expanded low-interest loan programs. The state would craft policies to boost residential, commercial and industrial solar use, and it would provide grant funding for businesses to install EV-charging stations in their parking lots and, for residents, in their homes. Open space is also a goal, the state said, outlining a policy to launch prairie restoration for land that's been destroyed by commercial, residential and industrial development. Montana Montana's goals are largely focused on agriculture and forestry initiatives, but on the property front, there's a focus on decarbonizing industrial facilities through a mix of electrification, solar thermal health, biomethane, low- or zero-carbon hydrogen and other low-carbon energy to reduce emissions. Existing voluntary grant, loan and rebate programs that fund efficiency upgrades in homes and businesses would be expanded, as would incentives for commercial, nonprofit and government buildings to improve energy efficiency. Nebraska Nebraska would focus on a range of incentives for energy efficiency, electrification and weatherization for industrial, commercial, agricultural, public and nonprofit buildings. Low- and middle-income residents could receive rebates on purchasing heat pumps and water heaters, as well as assistance to bring homes up to current code or rectify health and safety issues so they're eligible for weatherization and other programs. Solar is another big focus, with incentives for solar panels on unused or contaminated land and at agricultural or industrial facilities, as well as rooftop solar on commercial and residential properties. Nevada Nevada would incentivize new buildings under construction to go beyond current energy efficiency standards, and it seeks to expand retrofit and upgrade programs in buildings. The state is working on turning industrial sites and brownfields into clean energy hubs, encouraging renewable energy and green hydrogen production near industrial sites. The Nevada Clean Energy fund would be increased to enhance retrofitting and weatherization, and officials would explore using R-PACE and C-PACE programs to support residential and commercial weatherization and retrofitting. It would also explore alternative financing like community land trusts and a revolving loan fund. High-efficiency, all-electric new buildings could be eligible for density bonuses, streamlined permitting and tax abatements, and implementing renewable energy would open up even more rebates and incentives, the state said. Density bonuses and streamlined permitting are also options for incentivizing EV-chargers and rooftop solar in multifamily housing, according to the report. New Hampshire Federal funding would cover costs associated with utility system upgrades to support EV charging at government buildings, small businesses in the hospitality and tourism industries like restaurants and ski areas, state parks, and are or near multifamily buildings. Existing programs would be expanded to prioritize heat pumps and weatherization in residential buildings, and state officials would look to implement additional grants, loans or rebates to boost the measures. New Jersey New Jersey has a goal of installing zero-carbon emission space heating and cooling and weather systems into 400,000 residential properties and 20,000 commercial properties, which it plans to do through a "one-stop shop" for resources about state and federal rebate funding. The state would adopt the latest energy conservation codes for residential and commercial buildings and explore adopting a stretch code. The state would pilot community, campus or neighborhood-scale district geothermal system projects, and it would explore adopting a clean heat standard. New Mexico New Mexico's priority measures build on the state's EO 2019-003 framework including pre-weatherization for low-income residential building owners, energy efficiency community block grants and decarbonization of low-income and disadvantaged building owners. New York New York would focus on changing current land use planning and zoning practices to promote housing diversity, affordability, sustainable and energy efficient development and multiple modes of transportation. The state also wants to create green and resilient public facilities and implement large-scale reforestation. North Carolina North Carolina would explore building energy audits and incentives, develop a revolving loan fund for energy efficiency and electrification projects at public, private, institutional and industrial buildings, create low- or no-cost bridge loan options for energy efficiency, and encourage utilizing its "guaranteed energy savings performance contract" to implement and finance major facility upgrades in government buildings. If funded, the state would establish decarbonization programs through expanding combined heat and power deployment for industrial, large commercial and public buildings, as well as incentivizing electric residential appliances through rebate programs. Technical assistance, gap funding loans for tax credits, revolving loan funds, and programs targeting small businesses in low-income or disadvantaged communities are possibilities to encourage emissions reductions, according to the action plan. State officials would investigate revising residential building codes to require or recommend pre-wiring for EV-charging, and they ant to expedite permitting and review for EV-charging infrastructure. North Dakota North Dakota would expand the state's Energy Conservation Grant program to fund public buildings' electrification and energy efficiency upgrades. The state is also seeking funding to upgrade streetlights to LED lighting in Fargo. Ohio Ohio would consider updating building codes to require EV-charging capability, and it wants to incentivize renewable energy like solar and wind and to increase the efficiency of residential, commercial, public and industrial buildings. Funding would allow for incentives to all asset classes to integrate renewable energy like solar arrays into new construction, to streamline permitting, and to support utility-scale renewables or improve grid interconnection in projects. With a focus on targeted finance incentives like low-interest loans or rebates for improved efficiency measures in buildings and using low-carbon construction materials like cross-laminated timber, recycled steel and low-embodied-energy concrete, the state would encourage changes to how buildings are constructed. It's a move that could also lead to updating state and municipal level building and energy codes, according to the plan. Officials would eye financial incentives like tax credits and grants for adaptive reuse of commercial and industrial buildings, and they would collaborate with utilities for additional electrification incentives. Oklahoma Oklahoma's real estate climate goals center on solar development: incentivizing solar on farms and for industry, municipalities and universities to install solar and battery storage. Energy efficiency programs like updating HVAC in buildings, improving lighting and upgrading old refrigerants in commercial spaces is also a priority. Oregon The Oregon Department of Energy is currently finalizing a Building Performance Standard requirement expected in late 2024, so the state is proposing to add an incentive for owners who comply with the new requirements early and voluntarily. The new regulations would be enforced as early as 2028, but the requirements are tiered depending on building type and size. Oregon would also expand its Multi-Family Energy Program to serve affordable housing projects in rural and other areas of the state that are currently ineligible for energy efficiency upgrades because of their current utility providers. The state would also incentivize heat pump installation and weatherization, and it would craft policy to incentivize developing "space-efficient housing," meaning dwellings around 1,100 square feet, in a range of housing types from studios to three-bedroom houses. Pennsylvania Pennsylvania is investigating legislative updates such as requiring that 30% of electricity should come from renewable energy by 2030, authorizing community solar, and incentivizing localities to reconsider zoning laws that promote renewable energy in commercial, residential and industrial buildings. Officials would look to expand EV-charging infrastructure, including seeking out landowners and federal properties close to highways that may host charging infrastructure, and implementing a tax credit or rebate program for EV chargers at homes. Lastly, the state would prioritize funding, policies and programs to electrify and update building efficiency, including revising permitting and zoning to support construction and providing retrofitting incentives. Rhode Island Clean heat would be a goal of Rhode Island's climate policy. The state wants to expand the Clean Heat RI program to incentivize heat pump adoption and pre-weatherization work. Investing in EV-charging infrastructure at workplaces and multifamily units is also on the list, as is incentivizing battery storage and installing solar on commercial and previously disturbed lands. If funded, the state would also advance the Rhody Express train service between Providence Station, TF Green Airport and Wickford Junction. Its goal is to commence operation by fall 2025. South Carolina Much of South Carolina's hopeful policy would focus on land conservation and agriculture, prioritizing conserving and restoring high carbon-storage land, expanding its Climate Smart Forestry and Climate Smart Agriculture pilot programs, and extending and expanding existing weatherization programs being carried out by housing authorities and nonprofits. Tennessee Tennessee would provide incentives for residential, commercial and industrial building sectors to make energy-efficient improvements like space heating and ventilation, energy efficient lighting and weatherization. The state would also implement programs to expand EV-charging infrastructure. Texas Texas has few property-related priorities, but the state wants to promote combining solar arrays with biogas at closed landfills and adding solar to commercial and residential buildings. The state would also promote switching to electric heat pumps, weatherizing homes, reforesting agricultural land no longer in use and efficient irrigation systems in agriculture. Utah Utah would develop a rooftop solar incentive program and use federal funding to incentivize EV chargers at multifamily housing and workplaces across the state through one-time grants and technical assistance. Federal funding would also allow for offering whole home energy retrofits and new home updates through ongoing grants, and to offer incentives for weatherization and residential heat pump installation for low-income households. Vermont The existing Charge Vermont program would be expanded with federal funding to install public EV chargers, focusing particularly on multifamily properties where owners have been slower to adopt the technology and it tends to cost more. Vermont would also create five "energy navigator" positions to work with low- and moderate-income families to transition home energy systems to cleaner technologies. Developers would be incentivized to exceed the state's building standard with a focus on the building envelope, particularly affordable housing developers, with a more realistic "per-unit incentive" model. Vermont currently acquires between seven and 10 retired farms per year for conservation, an effort that would increase to 10 to 15 per year with federal funding, as well as other strategic acquisitions to conserve land and enhance carbon sequestration. Virginia Renewable energy is a big focus for Virginia, which highlighted goals to accelerate offshore wind, solar and nuclear energy, expedite transmission line project approvals and expand solar deployment for low- and moderate-income families. The state would provide financing like property assessed clean energy, or PACE, to help property owners upgrade energy efficiency and renewable energy in buildings. It also seeks to expand incentive programs for energy audits and other site assessments. In the residential setting, the state would look to offer subsidies for weatherization and efficiency, with grants and incentives for low-income households, and it would offer incentives for retrofits. Programs would also incentivize energy efficiency and clean energy power generation at commercial facilities, including data centers. The state would also eye reforestation opportunities on brownfields and mine reclamation lands, and it would create reforestation and afforestation programs. Washington Washington has only two building-related measures: reducing refrigerant use in small businesses and decarbonizing campus energy systems. West Virginia West Virginia wants to encourage energy efficiency initiatives in commercial and residential buildings, while encouraging counties to submit proposals on their own initiatives for the specifics of how such efforts would roll out. The state is also eyeing the development of an automated energy use tracking software on state-owned buildings, to be filtered down to counties and other local governments for use. Wisconsin Wisconsin will focus on transit planning and implementing possible measures such as higher density along transit corridors, mixed-use zoning, increased parking fees, improved public transit systems and more walking and biking paths. The state would also expand funding for commercial and residential electrification and retrofitting, create a pre-weatherization program, and expand publicly accessible EV-charging along key commercial corridors. In a decision the Chinook Indian Nation on Thursday called groundbreaking for other Indigenous communities, the federal government determined that the tribe will receive more than $48,000 from an Indian Claims Commission judgment handed down half a century ago as compensation for the seizure of the tribe's ancestral lands.

The judgment also ends years of litigation against the U.S. Department of the Interior after U.S. District Judge Marsha J. Pechman in January 2021 ordered the federal agency to review the tribe's remaining claims, which sought federal recognition as well as access to the funds. "This victory confirms our legal heirship to the settlement funds from our 1970 victory before the Indian Court of Claims. It sets the stage for the immediate dispersal of those funds to the Chinook Indian Nation," said tribal Chairman Anthony Johnson in a Thursday press conference. "It reaffirms the nation as rightful heirs and sole political successors of the Lower Chinook and Clatsop people here at the mouth of the Columbia River." The Chinook Nation first sued the DOI in August 2017, claiming the tribe was entitled to federal recognition because its peoples' sovereignty had been recognized for more than a century in dealings with the federal government. Alternatively, the tribe sought a finding that agency regulations preventing tribes from repetitioning were invalid. The Indian Claims Commission decision to disburse the funds is 150 years in the making, according to Chinook Indian Nation Secretary and Treasurer Rachel Cushman, with the tribe hiring its first attorney in the 1890s to seek damages for land taken by the federal government. Members of the Chinook Nation were acknowledged as the legitimate heirs to the Lower Chinook and Clatsop people in 1958 by the Indian Claims Commission, she said. Following decades of legal battles, in 1970, in an order known as Docket 234, the commission awarded the Chinook Nation $48,692 for compensation for lands stripped from the Lower Band of Chinook and Clatsop Indians by the federal government in August 1851. Those funds were placed into a trust account for the tribe in 1972, but an agreement was never reached regarding their use and distribution despite the federal government's obligation to do so, according to Cushman. By 2011, the Bureau of Indian Affairs stopped issuing quarterly statements from the fund to the tribe, citing its lack of federal recognition, which forced the Chinook Nation to sue in 2017 for the judgment. Cushman said the process of getting the final judgment wasn't easy; however, through "some important champions" locally and within the BIA, the nation was able to propose a use and distribution plan that has also been accepted by the BIA's Northwest Regional Office, the DOI, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Congress. The $48,692, she said, doesn't represent the actual value of the nation's ancestral lands, but for now, it will remain untouched in its accounts with other investments that have been rolled into it. The judgment award also reinforces the Chinook Indian Nation's right to acquire the now-defunct Naselle Youth Camp, located on its ancestral lands, Johnson said. By transferring ownership of the facility to the tribe, the state of Washington "will begin to make reparations for nearly two centuries of harm to Indigenous communities," according to the tribe. Johnson said the judgment also supports the tribe's ongoing fight for "unambiguous recognition" of the community's existence and rightful title to the lands where they continue to live. "There's a vacuum at the mouth of the Columbia River that will exist until we are properly seated as the federally recognized tribe here," the chairman said. The federal government recognized the tribe in 2001 after a 21-year process with the BIA. However, 18 months later, that title was revoked after President George W. Bush's administration took office and a new review process was instated. "Politics got in the way and all the preliminary, positive determinations and our final determination, and anyone who hadn't made it through that review process had their recognition or their preliminary recognition taken from them," Cushman said. Since that recognition was rescinded, the nation has experienced "one after another of really horrific moments in our community that would have been mitigated with federal acknowledgment," Johnson said, adding that it continues to face ongoing threats from rising sea levels and climate change. However, the nation continues to push local federal government leaders, the BIA and others for federal recognition. During the 2022 midterm cycle, now-Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez pledged to introduce and champion legislation to restore the Chinook Indian Nation's status as a federally recognized tribe, according to Johnson. "By passing a Chinook Restoration bill, elected officials will have an opportunity to end cultural erasure, support Indigenous rights and recommit to a legacy of defending Native communities," he said. The Chinook Indian Nation is represented by James S. Coon of Thomas Coon Newton & Frost. The federal government is represented by Brian C. Kipnis of the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Western District of Washington. The case is Chinook Indian Nation et al. v. Zinke et al., case number 3:17-cv-05668, in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. Georgia Senate Republicans filed a formal complaint to punish Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis after she sought charges against former President Donald Trump under a new law aimed at sanctioning “rogue” prosecutors.