|

Chicago has finally signed a $10 million settlement with Uber Eats and Postmates to resolve the city's investigation into purported misconduct by the meal delivery platforms during the pandemic, saying Monday that the deal closes a two-year probe into the apps' practice of listing restaurants without their consent.

The city's probe stemmed from the unwanted listings of Chicago restaurants on the apps owned by San Francisco-based Uber Technologies Inc., according to Mayor Lori Lightfoot's office. The city said Uber Eats and Postmates also violated Chicago's emergency fee cap ordinance during the COVID-19 pandemic and engaged in other advertising-related misconduct. "The city contends that Uber charged food dispensing establishments in excess of 15% of these businesses' monthly net sales earned through its third-party food delivery services, in violation of the city's emergency fee cap ordinances," according to the 12-page settlement signed in November by Sarfraz Maredia, Uber Technologies' vice president of delivery at Uber Eats, and Stephen J. Kane, deputy corporation counsel for Chicago. Betsy A. Miller, a Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC lawyer who represented Chicago in the matter, told Law360 on Monday that Chicago in 2021 began to receive a variety of complaints from restaurants about the Uber Eats, Postmates, Grubhub and DoorDash delivery apps. The restaurants complained that the apps' commissions were too high, that eateries were being listed without permission, and that the apps were engaged in deceptive pricing on their platforms. "During the pandemic in Chicago, half of the city's 7,500 registered restaurants closed at some point," Miller said. "Consumers needed to get their food, restaurants were trying to provide it, and this technology was in some ways making it possible, but restaurants also were reporting significant concerns of potential misrepresentations and unfair business practices. All companies have a right to try to form a business model in a safe, honest and fair marketplace and see if it works. But when the city began investigating, what it found was a variety of potential violations of its consumer protection laws." The city reached out to all three companies about the possibility of resolution without litigation, but it was only with Uber that settlement talks proved fruitful, Miller said. Separate suits Chicago filed against GrubHub and DoorDash in August 2021 remain pending. They accuse those food-delivery platforms of using deceptive practices to fool customers into paying higher prices, claiming that the companies violated the city's municipal code by advertising order and delivery services from restaurants without their consent, engaging in bait-and-switch tactics by jacking up prices at the end of a delivery, and advertising menu prices higher than if a customer ordered directly from the restaurant. The federal court now presiding over Chicago's suit against DoorDash has denied DoorDash's motion to dismiss, and the parties are currently engaged in the discovery process. Meanwhile, the state court presiding over the city's suit against Grubhub denied part of Grubhub's motion to dismiss and requested supplemental briefing on another aspect of Grubhub's motion. The parties completed the supplemental briefing and will appear for a hearing on Dec. 13. Lightfoot said in a statement that the Uber settlement reflects Chicago's commitment to a fair marketplace that protects businesses and consumers from illegal activity. "Chicago's restaurant owners and workers work diligently to build their reputations and serve our residents and visitors," the mayor said. "That's why our hospitality industry is so critical to our economy, and it only works when there is transparency and fair pricing. There is no room for deceptive and unfair practices." The city asserts in the settlement agreement that Uber deceptively advertised that Eats Pass and Postmates Unlimited subscribers would receive "free delivery" or "$0 delivery fees," and that it deceptively advertised that certain merchants were "exclusive to" or "only on" the platforms. In addition, Uber allegedly linked its platforms to the "Order" buttons on merchants' business listings on Google Search and Google Maps without adequate disclosure to consumers and without the merchants' consent, the settlement said. Uber denies the city's contentions, according to the settlement. "Uber maintains that Uber accurately advertised merchants as 'exclusive to' or 'only on' the platforms where merchants expressly agreed to be exclusive on the platforms; and ... Uber states on information and belief that Google LLC controlled whether the platforms were linked to the Order buttons in the merchants' Google business listing," the settlement said. Ultimately, following the city's June 28, 2021, cease-and-desist demand, Uber completed the removal of unaffiliated Chicago merchants listed on its platforms and agreed not to list any unaffiliated merchants without written consent in the future, according to the settlement. The $10 million deal includes Uber's $3.33 million payment to Chicago in September 2021 after the city discovered the fee-capping misconduct, a new payment of $2.25 million to restaurants that were charged commissions above the limits set by the city's emergency fee cap, $2.5 million in commission waivers to restaurants listed without their consent, and a $1.5 million payment to cover the city's investigation costs and fees. A spokesperson for Uber said the tech giant is "really pleased" to have found an outcome that worked for restaurants and the city. "We are committed to supporting Uber Eats restaurant partners in Chicago and are pleased to put this matter behind us," the spokesperson said in a statement. The city in the Uber matter is represented in-house by Stephen J. Kane and Peter Cavanaugh, and by Betsy A. Miller, Peter Ketcham-Colwill and Johanna M. Hickman of Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC. Counsel information for Uber was unavailable.

3 Comments

One of the oldest Catholic dioceses in the United States announced a settlement agreement Tuesday to resolve a bankruptcy case in New Mexico that resulted from a clergy sex abuse scandal.

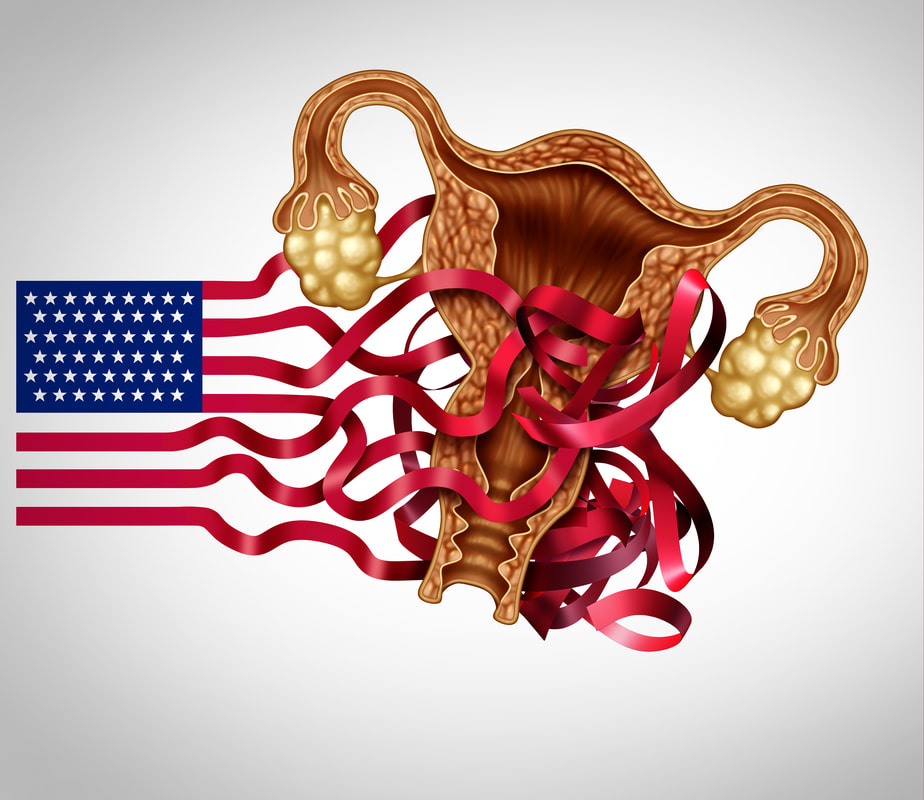

The tentative deal totals $121.5 million and would involve about 375 claimants. The proposed settlement comes as the Catholic Church continues to wrestles with a sex abuse and cover-up scandal that has spanned the globe. Some of the allegations in New Mexico date back decades. The chairman of a creditors committee that negotiated the agreement on behalf of the surviving victims and others said it would hold the Archdiocese of Santa Fe accountable for the abuse and result in one of the largest diocese contributions to a bankruptcy settlement in U.S. history. It also includes a non-monetary agreement with the Archdiocese to create a public archive of documents regarding the history of the sexual abuse claims, committee chairman Charles Paez said. “The tenacity and courage of New Mexico survivors empowered us to reach a recommended settlement that addresses the needs of the survivors on a timely basis,” he said in a statement Tuesday. The Archdiocese of Santa Fe filed the Chapter 11 bankruptcy case seeking protection from creditors in 2018. The settlement still must be approved by the abuse victims. It includes funds from sales or property and other assets, contributions from parishes and insurance proceeds. It does not include settlement of any claims against any religious orders, lawyers for both sides said. “The church takes very seriously its responsibility to see the survivors of sexual abuse are justly compensated for the suffering they have endured,” John C. Wester, archbishop of Santa Fe, said in a statement Tuesday. “It is our hope that this settlement is the next step in the healing of those who have been harmed,” he said. In New Mexico, some 74 priests have been deemed “credibly accused” of sexually assaulting children while assigned to parishes and schools by the Archdiocese, which covers central and northern New Mexico. Established in the 1850s after the Mexican-American War, the Archdiocese of Santa Fe filed for reorganization in late 2018 to deal with a surge of claims. An estimated $52 million has been paid in out-of-court settlements to victims in prior years. “No amount of money can undo the pain and trauma that our clients and their families have suffered,” Dan Fasy, a lawyer who represented some of the victims, said Tuesday. “But we hope this settlement can bring some form of closure and healing to the abuse survivors we were privileged to represent.” Soon after Shannon Lucas began serving a sentence at a Colorado halfway house, her medication began to disappear. Lucas had been sentenced to eight years in community corrections in lieu of prison for her role in a 2018 burglary involving her ex-boyfriend. At 41, she had never been in trouble with the law before. “I did believe that I was in a place that was for justice,” she said of her first weeks at the Larimer County Community Corrections facility in Fort Collins in October 2018. “I really thought going in there that I was going to be protected.” That would change less than a month later when she reported the theft of her prescription medications, which treat her post-traumatic stress disorder and severe anxiety. Instead of help, she got a lesson in how little recourse residents of these facilities have to address wrongdoing in the system. Lucas filed a complaint with management, which, instead of investigating, wrote her up for “medication misconduct.” Her lawyer requested security footage from the facility that might show who’d taken the pills. A judge ordered that it be given to the attorney on the condition that it not be released to anyone else. Hand and Emily Humphrey, director of Larimer County’s criminal justice department, did not respond to requests for comment. Halfway houses hold residents’ medications and provide doses under supervision. And the Larimer County Community Corrections facility had a documented problem with tracking medications, according to state records. A 2016 audit found that 1 in 4 of the medication counts that auditors reviewed were inaccurate and that staff were not “consistently following policy and procedures” to address inaccuracies. Auditors said corrective action was needed. A 2019 audit found that the facility did not have procedures for disposing of medications. State auditors have not reviewed the facility’s medication practices since. When residents of Colorado’s halfway houses believe they are victims of wrongdoing, they are often left with few options for restitution in a system that lacks a streamlined, independent complaint process and does little to allay their fears of retaliation. Each facility is required to have a grievance policy, but dozens of residents from multiple halfway houses told ProPublica that they didn’t use it because they feared staff would retaliate. Even residents who’d graduated from a program said they were reluctant to criticize their old facility because their parole officer could send them back there. A person can be expelled from a program for “any reason or for no reason at all,” a 2012 law says. People who get expelled are typically incarcerated or resentenced. A 2017 audit of a different Colorado facility, ComCor, found that formal complaints were not “consistently maintained, reviewed or responded to.” Clients said they believed complaints “simply wound up in the trash,” auditors wrote. Mark Wester, the executive director of ComCor, said that the facility allows “clients to work in the community, be productive citizens, receive client centered treatment, while having accountability and supervision that improves community safety.” Wester did not respond to a request for comment about the handling of complaints. The state has the power to investigate residents’ complaints but it rarely does, according to Katie Ruske, manager of the state’s Office of Community Corrections. Complaints submitted to the state are forwarded to one of the local community corrections boards, which ProPublica found often look past violations or fail to follow up to see if problems are addressed. Ruske, who has held her job since 2018, could recall only one such investigation, which involved an alleged violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Starting in 2023, the state will review client complaints as part of its audits. At the Larimer County Community Corrections facility, Lucas noticed in late October 2018 that more pills had disappeared. Lucas asked the staff member on duty to count them: 24 pills were missing. In a panic, Lucas submitted a second complaint to staff and called 911. Lucas said she needed documentation to replace the medication before she went into withdrawal. “I can have seizures, I can die if I don’t take my medication,” Lucas said. A Larimer County Sheriff’s Office incident report indicates that Lucas spoke to Officer Aaron Hawks, who suspected she was taking more than the prescribed amount of her medication. (An internal affairs investigation would later find that the officer violated policies, including failing to maintain an “impartial attitude” toward Lucas by calling her “a felon” and referring to community corrections staff as “vetted.” The report states he did not gather the evidence that would be necessary to conclude Lucas was at fault.) The Larimer County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to a request for comment. The facility responded by issuing Lucas a Class 1 violation — the most serious — for submitting a “false” police report. Such violations can result in termination from a program, according to the facility’s guidebook. “If I am revoked from this program, I am going immediately to prison” for eight years, Lucas said. “I was so scared I wasn’t going to be able to see my daughters.” Lucas appealed to management, who quickly denied her complaint. She wrote another appeal and met with the facility’s assistant director, who told her that she too believed Lucas was responsible for the missing medication, Lucas said. Lucas was then required to attend an administrative hearing with management to determine if she would be terminated from the program. Her request to have a lawyer present was denied. She was ultimately allowed to remain in the program, but her sentence was extended by a month, according to court documents. Under the direction of her doctor, she began receiving weekly prescriptions instead of monthly so she could keep a closer eye on her medication. But pills continued to disappear. In March 2019, she gave her new prescription to a staff member, Lauren Hand. Lucas recalls the correctional services specialist telling her, “Shannon, there’s two pills missing but I’m not gonna say anything.” A month after Lucas left the facility in April 2019, Lauren Hand was charged with two misdemeanors and a petty offense for unlawful possession of a controlled substance, official misconduct and theft. She resigned shortly after, according to an incident report. By then, Lucas had graduated from the residential program and moved home to complete her sentence with frequent check-ins at the facility. Lauren Hand, who is the daughter of the facility’s director, Tim Hand, did not respond to requests for comment. The outcome of the charges against Lauren Hand is unclear because the documentation is not public. According to Raymond Daniel, records manager for the district attorney’s office in the 8th Judicial District, the case would still appear in public records even if the charges were dropped. However, if the case was sealed or expunged, the public would not be able to view the records, he said in an email. Hand worked at another halfway house in Boulder before accepting a position at a youth detention center operated by the state’s Division of Youth Services in October 2021, according to her LinkedIn profile. As of January 2022, she no longer worked there, according to a spokesperson for the agency. Lucas filed a lawsuit over her stolen medication against Lauren Hand and other staff members at the Larimer County Community Corrections facility, as well as the board of county commissioners and the local community corrections board. Lucas alleged that staff at the facility retaliated against her for reporting the missing medication to police. The judge dismissed the case in July 2022, saying, among other things, that Lucas’ allegations were overly broad. Lucas has filed an appeal. Though Lucas is back at home with her daughters, she is required to report to the facility for drug tests, sometimes multiple times a week, and for meetings with her case manager. She said it’s a struggle to enter the facility without having a panic attack. Employees at the halfway house emphasize the importance of taking responsibility for one’s actions, she said, but staff aren’t always held to that standard. “They still say that I was stealing my medication,” Lucas said. “They literally could have just done the right thing. They could have just listened to me.”

Feds arrest Texas man charged with threats to Boston doctor who cares for transgender children12/6/2022 The 38-year-old Hill Country man faces up to five years in prison if convicted. A Texas man was arrested Friday on a federal charge that he left a threatening voicemail message for one Boston doctor who provides care to transgender people, according to the U.S. attorney’s office in Massachusetts. The man, Matthew Jordan Lindner, 38, of the Hill Country town of Comfort, was charged with one count of transmitting interstate threats. Comfort is in Kendall County, about 50 miles northwest of San Antonio. Lindner, whose company Lindner Ammo was a federal firearms licensee in 2019, is accused of leaving a voicemail message on Aug. 31 threatening to kill the doctor, who works at the Boston-based National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. An FBI agent stated in an affidavit that after the phone call to the Boston doctor, Lindner called two other phone numbers assigned to a Rhode Island university where the doctor is a faculty member. The calls were made from his company’s number, according to AT&T phone records cited by federal investigators. Lindner was arrested Friday morning and made an initial appearance in the Western District of Texas. He is being held without bail, according to The New York Times. He will appear in federal court in Boston at a later date. If convicted, he could face up to five years in prison, three years of supervised release and a fine of up to $250,000. In the recorded message to the Boston doctor, Lindner said, “You’re all gonna burn,” according to prosecutors. He mentioned “a group of people on their way to handle” the doctor and said, “You signed your own warrant.” Lindner named the doctor in the voicemail and ended the message by saying, “You’ve woken up enough people. And upset enough of us. And you signed your own ticket.” That call lasted 41 seconds, the affidavit says. Prosecutors did not publicly share the name of the doctor who received the threat. Lindner did not respond to calls or text messages from The Texas Tribune. His lawyer declined to comment. The National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center, which is part of the Fenway Institute, provides educational programs and health care for the queer and transgender people. The center does not offer clinical care or referrals, according to its website. Hospitals and doctors across the country have received death threats over the health care they offer transgender children. Leading health care organizations in Texas say gender-affirming care is the best way to provide care for gender dysphoria, which is the distress someone can feel when their assigned sex doesn’t align with their gender identity. It includes medical, social and psychological support to help a person understand and appreciate their gender identity. Providers often work with counselors and family members to ensure patients have everything they need to navigate the health care system. According to federal prosecutors, false information began to spread online in August that Boston Children’s Hospital doctors were performing hysterectomies on children. They became the target of a harassment campaign based on misinformation from conservative social media accounts about the hospital’s transgender surgery program. Hospital staff told WBUR, the public radio station in Boston, at that time that they had received aggressive calls, emails and death threats for some providers. Hospital staff have said doctors do not perform hysterectomies or gender-affirming surgery on patients under the age of 18, the affidavit says. Lindner’s call to the Boston doctor followed these threats. “Mr. Lindner’s alleged conduct — a death threat — is based on falsehoods and amounts to an act of workplace violence,” said Rachael S. Rollins, the U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, in a press release. “The victim, a Doctor caring for gender nonconforming and transgender patients, should be able to engage in this meaningful and necessary work without fear of physical harm or death.” The U.S. Department of Justice said it has pledged to protect the rights of gender-nonconforming and transgender people, as well as the health care providers who render care and support. Joseph R. Bonavolonta, the FBI’s special agent in charge of the Boston Division, said in a statement that the doctor had been targeted because she was caring for gender-nonconforming children. “No one should have to live in fear of violence because of who they are, what kind of work they do, where they are from, or what they believe,” he said. Policing Pregnancy: Wisconsin’s ‘Fetal Protection’ Law Forces Women Into Treatment or Jail12/6/2022 Wisconsin is one of just five states in the country that allows civil detention for pregnant people accused of drug or alcohol use. These so-called fetal protection laws are one often-overlooked way the government exercises authority over pregnancy. Tamara Loertscher arrived at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Eau Claire, Wisconsin on Aug. 1, 2014 despondent. The 29-year-old had suffered depression all her life, but in recent months, her mental health grew especially desperate. She struggled to eat and get out of bed, thinking of harming herself. Severe hypothyroidism fueled her anguish. Untreated, it causes debilitating depression and fatigue. Loertscher had required daily medication since radiation treatment killed her thyroid. But she was unemployed and uninsured, and, facing a yearlong wait for BadgerCare, unable to afford the drugs. When one home test, and then another, indicated Loertscher was pregnant, she went to Taylor County Department of Human Services, saying she needed treatment she could not afford for depression and hypothyroidism. Workers directed Loertscher to the hospital’s emergency room where she voluntarily admitted herself to the behavioral health unit. Under “reason for admission,” the medical records quoted Loertscher: “ ‘I really needed help.’ ” An ultrasound showed a 14-week-old, healthy looking fetus. When Loertscher heard the news, she cried with relief. After several days of reading and resting on the psychiatric ward, with newly prescribed thyroid medication, antidepressants, prenatal vitamins and supplements coursing through her system, Loertscher felt ready to leave. But while she had checked herself in, she could not check herself out. The county had put a “hold” on her. The Taylor County Department of Human Services had issued a request for temporary physical custody under Wisconsin Act 292, dubbed the Unborn Child Protection Act. Drug tests upon Loertscher’s arrival had shown “unconfirmed” positives for THC, methamphetamines and amphetamines. Later, the state would contend she knowingly used drugs and alcohol while pregnant; Loertscher would insist she stopped as soon as she learned of the pregnancy. Today, 44 states and the District of Columbia have laws aiming to protect fetal development from drugs or alcohol. Wisconsin is one of just five states that allow civil detention for pregnant people accused of substance use. Its legal proceedings take place out of public view, under seal, with a low standard of evidence and often a court-appointed attorney for the fetus — but none for the person gestating it. The law can require forced addiction treatment for the duration of pregnancy. “The law is a means of allowing the (local health) department to begin working with pregnant individuals to help overcome challenges associated with various (alcohol or drug) concerns, limit the potential effects of continued use on the unborn child and receive necessary treatment and services to assist the individual towards recovery,” says Kay Kiesling, Outagamie County’s Children, Youth and Families manager. “This early intervention allows for a potentially safer environment for when the child is born.” But every leading medical association that considered these laws has condemned a punitive approach, saying it harms more than it helps. The National Advocates for Pregnant Women, a legal advocacy group, says Wisconsin’s fetal protection law is the most “egregious” of the civil statutes in the country. With abortion now largely inaccessible in Wisconsin, Act 292 could become more widely applied, worries Loertscher’s attorney Freya Bowen. The law applies to any “controlled substance,” even over the counter medications such as Sudafed, she says, and many people could fall under its purview. Bowen fears that “really ugly enforcement” could prevent a pregnant person from leaving the state to obtain an abortion. Once the court has exercised this jurisdiction, she says, “they’re free to do all kinds of stuff that are ‘in the best interests of the unborn child.’ ” Case starts with visit to doctor Loertscher’s legal entanglement began when social workers at the hospital and county worried that the drug use risked her fetus’ health and requested she attend residential treatment for substance use disorder. She refused because, she says, she didn’t have a dependency and had self-medicated in absence of affordable prescriptions. That afternoon, the county issued its hold. “They said they were doing it for my baby,” Loertscher recalls, crying, in an interview with Wisconsin Watch. “But they were hurting him, too.” Within weeks of the complaint, Loertscher would end up in jail. Her case was one of 387 that year in which county child protective services “screened in” allegations of “unborn child abuse” across Wisconsin for further investigation, and one of 67 with “substantiated” claims that a pregnant woman had harmed her fetus by using drugs or alcohol. Human embryos and fetuses — which the law terms “unborn children” — came under the auspices of Wisconsin’s Department of Children and Families in 1998. Amid the national “crack-baby” hysteria, politicians and press euphemistically called Wisconsin’s Act 292 the “cocaine mom” or “crack mama” law. Legal scholars say such laws undermine pregnant people’s bodily autonomy — particularly for those who are poor or women of color who are more likely to be involved with the child welfare or criminal justice systems. “They said they were doing it for my baby, but they were hurting him too,” One woman, Alicia Beltran of Jackson, Wisconsin, even ended up in shackles in 2013 due to past drug use, despite testing negative for all substances except Suboxone, which she used to wean herself off Percocet, during her pregnancy. Says Michele Bratcher Goodwin, a law professor at the University of California Irvine: “In terms of civil liberties, I mean, there’s nothing more extreme.” About 400 cases a year Since 2007, Wisconsin authorities have screened in an average of 382 complaints annually, meaning that about one pregnant person per day is investigated for unborn child abuse. But with limited publicly available data from the Department of Children and Families — and court records shielded from public view — it is unknown how many women, like Loertscher, have ended up incarcerated due to noncompliance. It is also unknown how many mothers have lost custody of their infants after birth because of the law. Yet separation happens far too often, suggests one self-described “jaded” state public defender who only agreed to speak anonymously for fear of repercussions on her clients. She says Act 292 enables “the systemic kidnapping of children from women — and families, sometimes — who have struggled with addiction.” A recent investigation by The Marshall Project, The Frontier and AL.com, co-edited and published in partnership with The Washington Post, found that since 1999, more than 50 women have been charged with child neglect or manslaughter after testing positive for drug use following stillbirth or miscarriage. Since its enactment, Wisconsin’s fetal protection law has weathered two high-profile challenges. Loertscher’s legal team — which included now-Attorney General Josh Kaul — was most successful, securing a federal court ruling that deemed the law unconstitutional. But the win was brief, and due to a technicality, the law remains in effect today. Loertscher’s case gives the public a glimpse at what can happen at its most extreme. While the law does not require county health officials and hospital workers to report such cases, a 2018 Pew study found Wisconsin practitioners “commonly” misinterpret their legal obligations — something researchers suggest the state should clarify. War on drugs leads to ‘crack baby’ myth In 1997, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that a Waukesha juvenile court lacked authority to detain a pregnant woman at a hospital until childbirth on the basis of drug use. Not long after, a bipartisan group of lawmakers gave it that very authority in Act 292, which gave “unborn children” from zygotes to embryos full human rights — the only state to do so. Bonnie Ladwig, a Republican representative from Racine who introduced the bill, testified: “Cocaine babies and children with fetal alcohol syndrome can be seen as abused children.” Health professionals warned the fear of punishment would discourage pregnant women from seeking prenatal care and substance use treatment. Some suggested the law would incentivize women to get abortions to avoid detention. And analysts — and even one of the co-sponsors — doubted its constitutionality. The nonpartisan Wisconsin Legislative Council and Legislative Reference Bureau advised that the liberty and privacy rights enshrined in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey would likely outweigh the state’s interest in “unborn human life before fetal viability,” according to the Collaborative for Reproductive Equity at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Writing in her book “Policing the Womb,” Goodwin, the law professor, says the media used anecdotal reports to fuel a hysteria over so-called “crack babies” — an ostensible “bio-underclass” doomed to lifelong suffering. “If this law had the face of middle or upper income white women at the time, it would not have been a law that would have won enactment or support,” Michele Bratcher Goodwin The racist crack baby myth cast Black, brown and Indigenous women as bad mothers and their infants as permanently damaged, Goodwin tells Wisconsin Watch. She notes that the former director of the National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect claimed — without evidence — that up to 15% of African American children would have “permanent brain damage” from gestational cocaine exposure, even though the majority of crack cocaine users are white. “If this law had the face of middle or upper income white women at the time, it would not have been a law that would have won enactment or support,” Goodwin says. A longitudinal study has since debunked the myth. Dr. Hallam Hurt, a neonatologist and pediatrics professor at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, followed children exposed to cocaine in utero for nearly a quarter of a century. Hurt found no meaningful differences in development or cognition between the groups with gestational cocaine exposure and without. But both groups — all children from low-income families — performed poorly, leading Hurt and her team to conclude that poverty more powerfully influenced a child’s well-being. A Wisconsin Watch analysis of DCF data found that today, Wisconsin child protective services disproportionately investigates allegations of unborn child abuse against Indigenous women, compared to their population size. The public defender says she represents a “very high” number of Native American women in Act 292 cases. ‘He is what gave me purpose’ Depression dogged Loertscher since elementary school, but antidepressants exacerbated her suicidal thoughts. She tried to die by overdose several times. A low point came when Loertscher passed out at a bar after drinking. A videotape surfaced showing her unconscious, being raped by multiple men. “As soon as I found out that he was going to be apart of us, everything was for him. He is what gave me purpose,” Tamara Loerstcher That’s when Loertscher began self-medicating with methamphetamine. The stimulant “helped her to get out of bed in the morning,” according to a complaint later filed in federal court. Marijuana also mellowed her symptoms, which her attorneys contend she smoked “fewer than 10 times” that year. Loertscher’s pregnancy by her then-boyfriend, now husband, compelled her to save her life — and her son’s. “As soon as I found out that he was going to be a part of us, everything was for him,” Loerstcher says. “He is what gave me purpose.” She says she disclosed her drug use in hopes of ensuring her son’s health and tried to explain her inability to afford prescription treatment to hospital staff. “I was trying to self-medicate,” Loertscher says. “They didn’t care. It’s like, they had a certain set of protocols that they had to follow, and it’s like, erase the woman out of the equation.” ‘I don’t matter at all’ Less than 24 hours after Taylor County requested temporary physical custody, a social worker ushered Loertscher into a hospital conference room, where she listened into a court hearing on speakerphone. On the other line were the court commissioner, corporation counsel, human services staff and another lawyer — court-appointed to represent Loertscher’s fetus. She lacked an attorney. “It just kind of confirmed the feelings of ‘I don’t matter at all,’ ” Loertscher recalls. Pregnant people going through Act 292 proceedings are eligible for state public defenders if they qualify by income. But Sandra Storandt, a social worker with Jackson County, says pregnant women in her county typically lack representation in this initial hearing because it happens so quickly — by law, within 48 hours of filing a request for temporary physical custody. The authorities wanted Loertscher to remain at the hospital until “medically cleared” and then transferred to a licensed treatment facility. A center in Eau Claire, over an hour from her home in Medford, had availability. In Wisconsin, pregnant women get priority placement in substance use treatment centers. A court transcript documents the hearing. Asked if she understood the hearing’s purpose, Loertscher said she would not answer questions without an attorney. The court recessed in a failed attempt to find an attorney to represent her. Loertscher left the conference table and asked to make a call. “It just kind of confirmed the feelings of ‘I don’t matter at all,’ ” Tamara Loertscher “I just followed Tammy down the hallway to her (hospital) room,” the social worker told the court. “She doesn’t want to be part of this.” The commissioner ruled that she had waived her right to participate, noting that they had limited time before they would have to release her. At this point, authorities had another 24 hours. A social worker went to Loertscher’s room, holding a phone so she could hear. The county called an obstetrician/gynecologist who claimed Loertscher admitted to knowingly using methamphetamine while pregnant. Prefacing that she was “not an expert witness,” the doctor explained some concerns around methamphetamine use during pregnancy, including low birth weight and possible learning disabilities and inattention to prenatal care. In 2022, the National Advocates for Pregnant Women reviewed numerous studies and reports about gestational exposure to various drugs, concluding, “Research tells us that there is no scientific evidence of unique, certain, or irreparable harm for fetuses exposed to cocaine, methamphetamine, opioids, or cannabis in utero.” The doctor recommended residential treatment; the fetus’ attorney asked the court to force Loertscher into treatment “for this child to have a chance of literally being born.” Afsha Malik, formerly a research and program associate at the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, says Wisconsin’s “probable cause” standard means courts need only the “suspicion” of drug use to order commitment. The four other states which permit civil commitment — the Dakotas, Oklahoma and Minnesota — all require “clear and convincing evidence.” The commissioner found enough evidence to detain Loertscher at the Eau Claire hospital until discharging her to the residential treatment facility. Separation threatened After the hearing, Loertscher says the hospital staff warned her she would lose custody of her baby as soon as it was born. Storandt, the Jackson County social worker, says that in her county, the likelihood of a child staying with a parent is higher than their chance of removal, and separation isn’t always permanent. But the state public defender practicing in northwestern Wisconsin, who spoke anonymously, says she’s seen newborns taken from parents “many, many times.” This public defender estimates she handles about one Act 292 case per year. Unlike Loertscher, many of the clients are moms with prior involvement with the child welfare system. Their chief concern: “Am I going to be able to keep my baby after they’re born?” The attorney says she’s seen foster care requests issued the moment a mom tries to take her infant home from the hospital, “even when I’ve had them make it through treatment, and the babies are born clean, and there’s nothing in their system.” The conditions required to keep one’s children, or get them back, might appear simple enough: keeping regular contact with a social worker, attending supervised visits, taking parenting classes. But even these may be “unrealistic” for families without reliable transportation, a stable address or a working phone, the public defender says. “Our system is not built to genuinely help parents, who are indigent, who are drug addicted, who are mentally ill, to actually comply with some of the conditions that counties and states want them to comply with in order to get their kids back a lot of times,” the lawyer says. Deciding to fight Loertscher, for the most part, resisted the process. “I just found out that I was pregnant, and they were threatening to take him away,” she says. “I felt like I had to fight for the both of us.” Two days after the hearing, Loertscher was supposed to transfer to residential treatment. She refused a blood test required for admission, and instead convinced the hospital to let her go home. She left with prescriptions for her thyroid and depression and plans to see a local nurse practitioner. The discharge summary noted Loertscher didn’t think she misused substances, and that she “would like to keep the baby and that she would be caring for her pregnancy.” At the courthouse, Loertscher’s case escalated. Taylor County’s corporation counsel requested to take her into immediate custody, and a judge agreed. Over the next week, police twice attempted to arrest Loertscher to ensure her presence at court hearings. Loertscher’s family also tried to hire an attorney, but they could not afford the retainer fees. So on Sept. 4, 2014, Loertscher appeared at her plea hearing without counsel. She disputed the county’s claims that she had committed unborn child abuse, setting the case for trial. If a jury determined her guilty with “reasonable certainty” by “clear, satisfactory and convincing” evidence, the court could detain her for the rest of her pregnancy. That is, if she ever went to trial. But something else got in the way first. Finding she had violated an earlier court order to go into treatment by refusing the required blood test, the judge sentenced her to comply — or serve 30 days in the Taylor County Jail. “I can’t have the deputies hog-tie you and take you to that treatment center,” the judge said. “That’s a decision you’ll have to make. But I can punish you if you decide not to obey that order.” Hauled off to jail Leaving the hearing, Loertscher reflected on her options: inpatient treatment or jail. Of the two, it was obvious which she’d prefer. But accepting treatment also meant accepting a diagnosis with which she disagreed. It meant adopting an incorrect label — this time, “addict” — that someone else chose for her. “They said they were going to put me in treatment and keep me there until I had my child, and then they were going to take him away,” she says. “So that’s where I’m like, ‘Well, I’m just going to have to go to jail then.’ ” But jail brought its own risks, including missed prenatal appointments. The jail also refused to provide in-house care until she took a pregnancy test, which she initially refused. According to Loertscher’s eventual complaint, when a guard taunted her about taking a “piss test,” Loertscher lashed out. She yelled obscenities through the closed door. The guard “grabbed” her by the arm, “tried to pull her out of the cell,” threatened her with a stun gun and then marched her into solitary confinement. She spent about 36 hours in a “cold and filthy” windowless room with feces on the floor and walls. Her metal bed frame had only a “thin mattress and blanket” at night. While in solitary, Loertscher says she received another threat. If she didn’t provide a urine sample, she’d remain locked up for the rest of her pregnancy and would have her baby there, which the National Perinatal Association warns is bad for the health of the child and parent. Eventually, Loertscher found a number for the public defender’s office scrawled on a piece of paper by the phone. She called, and an attorney negotiated her release. She agreed to undergo an alcohol and other drug abuse assessment, comply with recommended treatment and pay for and submit to weekly drug tests, among other things. After 18 days in jail, Loertscher went home. But she was far from free. ‘Born into chaos’ A week after she left jail, she received a letter from the Taylor County Department of Human Services, saying it had made a separate “administrative finding that she had committed child maltreatment” — a designation separate from her court case and consent decree. “I had to protect us,” Loertscher recalls, “because what they were doing was so ridiculous.” So she connected with the National Advocates for Pregnant Women, which teamed up with New York University School of Law and a Madison-area law firm. At the end of 2014, Loertscher filed a lawsuit in federal court, arguing she had been “deprived of liberty and numerous, well-established constitutional rights” after seeking health care. A month later, during a weekly drug test, her water broke and Loertscher went into labor. At the hospital, she says staff questioned her about Act 292. A police officer stationed outside her room heard the same threat: if she did not cooperate, they would take her baby away. Says Loertscher: “He was born into chaos.” Her attorney raced from Madison to Eau Claire to intervene, but in the end, the hospital allowed Loertscher and her boyfriend to take Harmonious, their newborn, home. “He is my everything,” Loertscher says. “I just want to make him proud.” A court win — ‘then they took it away’ Over two years after Harmonious’ birth, the federal court ruled in Loertscher’s favor. The court found that Act 292 implicated fundamental constitutional rights “to be free from physical restraint” and “coerced medical treatment,” and it was “unconstitutionally vague.” Each element of unborn child abuse is wide open for interpretation, the judge noted. Its key terms “habitually,” “severe,” even “risk,” are all matters of “degree” that neither the statute nor departmental standards define. As a result, the law could be enforced against any pregnant person with a history of substance use disorder, he said, “regardless of whether she actually used controlled substances while pregnant.” The state was immediately barred from enforcing Act 292 across Wisconsin. “I felt like, at least it was for something,” she says. “And then they took that away.” Within a week, Republican Attorney General Brad Schimel appealed the decision. An appeals court panel ruled the injunction was “moot” because Loertscher had left Wisconsin two weeks after Harmonious’ birth, temporarily moving to Hawaii. “I beat myself up so much,” Loertscher says through tears. “If I would have stayed in that shithole, it (ruling) would have stuck.” The law remains in effect today. At least one substantive change to procedure has been made, although it came before Loertscher filed her lawsuit. The Department of Children and Families no longer allows social workers to determine whether or not a pregnant person has committed “maltreatment.” Instead, they only determine whether or not to require “services,” such as counseling or treatment. “I don’t understand how they can acknowledge that something is unconstitutional, but keep it going,” Loertscher says. “That makes it seem like our constitution doesn’t mean anything to certain people, like, certain people’s rights don’t matter at certain points.” Wisconsin’s confusing standard Fetal protection laws place pregnant people into a distinct legal class, says Malik, who at the time she spoke to Wisconsin Watch was with the National Advocates for Pregnant Women. While most drug-related offenses relate to possession or distribution, these laws punish pregnant women for use — even if these are legal substances, such as alcohol, which are lawfully obtained. The behavior identified as unborn child abuse in Wisconsin falls under standards that even those charged with enforcing the law struggle to describe. It requires that a pregnant person “habitually lacks self-control” regarding alcohol or drug use. The habitual lack of self-control must be “exhibited to a severe degree” and create a “substantial risk” that the fetus’ — and eventually, the newborn’s — physical health “will be seriously affected or endangered” unless the parent receives treatment. When asked by email to clarify what “habitually,” “severe degree” or “serious harm” means, Department of Children and Families communications director Gina Paige said the law “did not include any further language or define these terms.” Enforcement varies by county. Only Dane, Jackson and Outagamie gave Wisconsin Watch insight into their procedures. Another county provided background information on its approach on the condition of anonymity. A social worker from Jackson provided an on-the-record interview, the others provided answers or statements via email. Officials from Brown and Ashland counties initially expressed interest in speaking but did not follow through with interviews or email responses. Dane County says it “does not endorse” placing people in a “locked facility to force treatment” and instead favors harm reduction, which it did not define. ‘Being quiet about it isn’t helping anyone’ Seven years after the birth of her healthy baby boy, Loertscher, who now lives in Georgia, is still scarred by her entanglement with Act 292. “They say that they’re doing it to protect the child, but in reality, at least in my situation, they didn’t care one bit,” she says. “It was all about, for some reason, proving that I was a bad person.” The detention, incarceration and legal battle has left her with further anxiety and depression. Loertscher has found it difficult to trust anyone outside of her immediate family, leaving her unable to work and even afraid to drive. The trauma she and her husband share manifests in overprotective parenting. But in the last two years, around the time Harmonious began school, Loertscher felt something shift within her: “I finally was like, ‘You know what? I’m not going to let them take all my power away.’ ” She started taking better care of herself, socializing more and giving interviews about her experience, because “being quiet about it isn’t helping anyone.” “What they did didn’t break us, if that was what they were trying to do,” she says. “And our son turned out amazing. He’s smart and he’s happy.” The 7-year-old is “like a little fish” in the water and loves to read with his mom, and tell her jokes he picked up from books. His favorite, of late, asks: “What did the alien say to the vegetable garden? Take me to your weeder!” Loertscher has a message for anyone else caught up in Wisconsin’s fetal protection law. “I want to tell them that they can be brave,” she says. “They can come forward and they can say that what happened to them is wrong, because it was.” What to do if you are pregnant and struggling with substance use in Wisconsin There is currently no directory of Wisconsin-based doctors and midwives experienced in providing care to pregnant people with substance use disorder, says Dr. Charles Schauberger, who is board certified in both obstetrics and addiction medicine and has dedicated the past 10 years of his career to caring for pregnant women with substance use disorder. Enforcement of Act 292 varies depending on the county where one resides. But Schauberger’s experience tells him that “if a care team has the reputation of working hard to keep patients in treatment and providing great prenatal care, county health authorities, including CPS, are much more likely to back off.” Schauberger offered this advice for pregnant people with substance use disorders:

The National Advocates for Pregnant Women has created a fact sheet for healthcare providers and pregnant people, and offers this advice in a know your rights sheet:

St. Louis Can Banish People From Entire Neighborhoods – Police Can Arrest Them if They Come Back12/6/2022 Inside the Enterprise Center, the St. Louis Blues hockey team was losing a home game to the Edmonton Oilers. Outside, a man named Alvin Cooper was lying on a venting grate on a 38-degree night.

A St. Louis police sergeant asked him to move, according to an officer’s December 2018 report. Cooper refused. The sergeant and the officer pointed to signs that said “No Trespassing” and “No Panhandling.” Cooper said, “I ain’t going nowhere.” The officers tried to handcuff Cooper, one of them using “nerve pressure points on his jaw and behind his ear,” the other delivering “several knee thrusts” to Cooper’s right leg. The officers arrested Cooper and booked him on charges of trespassing and resisting arrest. Two weeks later, a city prosecutor dropped the resisting arrest charge, while Cooper pleaded guilty to trespassing and signed an agreement offered to him by the prosecutor saying that as a condition of his probation, he would stay out of downtown St. Louis for a year. The neighborhood order of protection, as the agreement is called, meant that Cooper could be arrested if he so much as set foot inside a 1.2-square-mile area — more than 100 city blocks — that is home to many of the organizations that provide shelter, meals and care to St. Louis’ homeless people. Other American cities order people to stay away from specific individuals or places, and some have set up defined areas that are off-limits to people convicted of drug or prostitution charges. But few have taken the practice to St. Louis’ extreme, particularly as a response to petty incidents, according to experts in law enforcement. Seattle and some of its suburbs, including Everett, have blocked off certain areas of their cities as “exclusion zones” where people who have been convicted of drug or prostitution offenses can be arrested. The practice has long been criticized by civil rights advocates, but city leaders say it has helped reduce crime. Cincinnati once barred people convicted of drug offenses from its own “exclusion zones.” But a court struck down the practice as a violation of the constitutional freedoms of association and movement, and the U.S. Supreme Court in 2003 let that ruling stand. The Chicago suburb of Elgin adopted rules in 2016 that ban people who have repeatedly caused nuisances from some sections of the city, but it has been enforced sparingly. In St. Louis, neighborhood orders of protection affect large swaths of the city and are typically in effect for a year or two, although some orders have had expiration dates in 2099, according to records obtained by ProPublica. A person who violates an order may face a fine of up to $500 or be sentenced to as long as 90 days in jail. Victor St. John, an assistant professor of criminology at Saint Louis University, said even limited bans may have a dire impact “in terms of individuals not being able to engage with family members or friends.” “It’s a restriction on resources that are publicly available to everyone else,” he said, adding, “I haven’t heard of entire neighborhoods.” Yet just how rare the practice is across the country is difficult to assess, in large part because it has not been closely tracked. University of Washington professors Katherine Beckett and Steve Herbert, who have studied Seattle’s efforts, said in their 2009 book, “Banished: The New Social Control in Urban America,” that banishment is “rarely debated publicly” and that cities’ tactics are “largely deployed without much fanfare.” “I think part of the problem is that these legal tools are very much under the radar,” Beckett said. When neighborhood orders of protection are employed in St. Louis, critics say that they are too often used against people with mental health issues or who may be homeless, and that banishing an individual from a large section of the city may violate their civil rights. They say the orders fail to address the underlying problems contributing to their behavior. Instead, they simply move problems from one part of the city to another. The ACLU of Missouri said that it had explored a lawsuit to challenge the practice a decade ago but eventually did not because the organization did not have enough information and did not have consistent contact with a potential plaintiff. “City courts violate the constitutional rights of Missourians when they issue broad, arbitrary banishment orders untied to any legitimate governmental purpose,” the group said in a statement. “The fact that such orders are used against people who have committed harmless, petty crimes only makes plain that the orders are about inconveniencing the vulnerable, and not about public safety.” Some people have been barred from multiple neighborhoods. Some have been arrested for violating their bans multiple times within a few days. “It reeks of redlining,” said Mary Fox, the longtime lead public defender in St. Louis who now heads the state’s public defender system. “It reeks of everything that happened before the Civil Rights Act went through — just allowing them to keep certain people out of their neighborhoods.” Neighborhood orders of protection are another way policing in St. Louis is employed on behalf of the wealthy and against those most vulnerable. A ProPublica investigation showed how residents of affluent city neighborhoods hire private policing companies to patrol public spaces and protect their homes and busineses, creating dramatic disparities in how local law enforcement is provided. Private policing and neighborhood orders of protection often go hand in hand, with private police officers doing much of the work to enforce the orders, according to emails obtained by ProPublica. The city’s Municipal Court paused issuing neighborhood orders of protection at the start of the pandemic — not because of any policy change but because the process requires the defendant to appear in court and city courts are closed to in-person proceedings. But police have issued citations for violations of the orders as recently as July 2021, records show. Some defendants also face active court cases for alleged violations. Moreover, a city ordinance authorizing the orders remains in effect, and St. Louis police are under orders to collect evidence that can help prosecutors pursue orders of protection. St. Louis Municipal Administrative Judge Newton McCoy said in an email that defendants may be subject to neighborhood orders of protection “on a case by case basis” as a condition of probation “if they repeatedly commit offenses in certain neighborhoods.” He said court officials are “working to determine next steps for when all in-person municipal court hearings will resume.” The banishments require the consent of the defendant, but some lawyers question whether defendants really have any choice but to sign. In one instance, a man was arrested for trespassing while gathering on a city sidewalk with friends across the street from a downtown homeless shelter. He agreed to stay out of downtown but was subsequently arrested for a violation and served three months in jail, a case highlighted by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “I don’t think the actual terms of the neighborhood order of protection were clear to my client,” said Maureen Hanlon, an attorney for the public-interest law group ArchCity Defenders. “It states that he consented to it, but he was unrepresented at the time.” She entered the case after his incarceration for violating the order, “which, on paper, he agreed to, but in reality, I really question whether or not someone can agree to an order like that without counsel.” ProPublica was not able to determine how many neighborhood orders of protection have been issued over the past two decades. Court cases are typically sealed after the successful completion of probation. It was also unclear if any remained in effect. Megan Green, who on Nov. 8 was elected president of the city’s Board of Aldermen and is the city’s second-highest ranking official, said she has long heard from advocates for the homeless who say the orders make it difficult for the city’s most vulnerable people to receive meals or other services. Green said she wants to study the use of neighborhood orders of protection to “understand the implications. And if we need to take a look at a revision, I think, potentially do that.” “If you are banning somebody from downtown from the area where services are, that makes it that much harder to address the needs,” Green added. She said she also found it problematic that “if you’re just banning somebody from a certain area, and never addressing the behavior, chances are that behavior just moves to another block or another neighborhood. “So I’m not sure how effective something like this is at achieving what folks are going for, either.” Neighborhood leaders and police officials have defended neighborhood orders of protection as a tool for residents and businesses to make their streets safer by sending a message to criminals that they are not welcome. St. Louis police Sgt. Charles Wall said the department merely enforces the orders once they’re issued. Jim Whyte, who manages a private policing initiative in the city’s upscale Central West End, said neighborhood orders of protection are “used all over the city to kind of address these very problematic people.” Whyte said that the orders were sometimes difficult to enforce. “If the person was involved in panhandling or a crime incident, I’d call the prosecutor and say, ‘Hey, this guy was down here Thursday violating the order.’” Whyte said that the prosecutor would ask if there was an arrest and he would say “like, ‘No, there weren’t any police around.’” In those cases, Whyte said, prosecutors would not support charging the person with a violation. Cooper could not be reached for comment. His mother, Karen Johnson, said her son, now 39, has suffered from schizophrenia since graduating from high school. His use of prescription medication, she said, led to reliance on street drugs and a life that spiraled into homelessness. During his ban from downtown, he moved out of the city and stayed with a family member in suburban Cool Valley. The court’s action to ban her son from downtown was “wrong,” his mother said. “That’s where he was getting a lot of help — the downtown area.” This fall, she said, he was shot and wounded in an assault while he was living in a hotel. The impetus for neighborhood orders of protection is murky. The St. Louis Board of Aldermen in 2003 unanimously passed the ordinance laying out penalties for violating orders, but it’s not clear if they existed before. Three of the bill’s four living sponsors — Jay Ozier, Dionne Flowers and James Shrewsbury — said they do not remember what prompted the measure. The fourth, Craig Schmid, could not be reached. None remain on the board. “Particularly if you’re talking about it in terms of panhandling or something like that, I don’t see how I could have been in favor of it,” said Ozier, who served from 2002 to 2003. The language in the ordinance suggests it was aimed at drug offenders. “Whereas, the illegal distribution, possession, sale and manufacture of controlled substances continues to plague our neighborhoods,” it reads. But in practice, the police in St. Louis have used the orders of protection more broadly. To obtain an order, a representative for a neighborhood must document that a person who has been arrested has repeatedly caused trouble there. A prosecutor can use this statement as part of the neighborhood’s request for the order of protection. The prosecutor can then offer the agreement to the defendant, typically in exchange for dropping one or more charges against them. The text of the order — with specific boundaries of the banishment area — is then added to a St. Louis-area criminal justice database, which can be accessed only by police and court officials. When police officers run the name of a person who has been issued an order of protection, the database will alert the officers. For several years, neighborhood leaders viewed the orders as a tool for taking back their streets — sending criminals a message that they are not welcome. In 2014, for instance, about 50 residents of the city’s Tower Grove South neighborhood successfully petitioned a Circuit Court judge to order a carjacking suspect to stay away as a condition of release. “The show of solidarity from the residents of Tower Grove South played an important part in the positive outcome of today’s hearing,” the neighborhood’s website boasted. “Congratulations TGS!” As late as 2015, the website for the city’s top prosecutor, Jennifer Joyce, featured a page where residents could view the names and photos of people who had been banished under neighborhood orders of protection. The circuit courts, which handle misdemeanors and felonies, have not issued a neighborhood order of protection at least since progressive prosecutor Kimberly M. Gardner succeeded Joyce in 2017. But the practice has persisted in Municipal Court, where defendants face infractions, typically do not have lawyers and cases receive little public scrutiny. Some cases can linger for years, as police repeatedly seek and enforce neighborhood orders of protection against the same people with little evidence that the orders are effective. In a report in 2017, a St. Louis police officer wrote that he was working for the department’s downtown bike unit and trying to combat a “rise in quality of life violations” downtown. He said a motorist complained about homeless people outside the city’s Dome, where the NFL’s Rams used to play. One of the men the motorist pointed to was Gary Accardi, who the officer said was a “well-known panhandler,” according to his report. Accardi was holding a cardboard sign that said: “Homeless, Please help. God Bless.” Four years earlier, in 2013, police had cited Accardi five times for violating a neighborhood order of protection, and he had spent 10 days in jail. As the officer approached, he wrote in his report, Accardi ran away yelling, “I don’t want to go to jail!” The officer wrote that he caught up with Accardi and put him on the ground to get him under control. Accardi was charged with panhandling, resisting arrest and impeding traffic. Weeks later, Accardi agreed in municipal court to stay out of downtown St. Louis for one year. Over the next few years, the order against Accardi was repeatedly extended and he was cited for violating it 17 times from July 27 to Oct. 17, 2018; on two occasions during that stretch he was cited twice in the same day. In April 2019, while St. Louis Cardinals fans packed Busch Stadium downtown for opening day, police officers spotted Accardi outside the stadium and issued him a summons for violating the order. The next day, Accardi was rifling through a trash can outside the stadium and another officer cited him yet again for the violation. Stephanie Lummus, a lawyer who has represented Accardi in some of his cases, said a judge in 2020 declared him incapacitated and placed him under a guardianship. The guardian, she said, ordered her not to speak on his behalf. Lummus said she frequently appears in municipal court on behalf of clients with cases on the court’s mental health docket — a special court day designed to match vulnerable people with services that can help them. “I would sit there and wait for my client,” she said. “And I’d watch these people on the mental health docket sign these neighborhood orders of protection unrepresented, not knowing what the hell was going on. And I was just like, This is not the place for that, you know. These people are on the mental health docket for a reason. Why are you doing this?” In some St. Louis neighborhoods, private police companies have enforced neighborhood orders of protection. Minutes from a 2018 meeting of a downtown community improvement district indicate that a private policing contractor had pursued neighborhood orders of protection for 25 “persistent offenders.” Officers working off-duty for The City’s Finest, St. Louis’ biggest private policing company, have enforced neighborhood orders of protection in the Central West End, emails show. “Neighborhood orders of protection are legal and issued by the courts,” the firm’s owner, Charles “Rob” Betts, said in an email. “If you have an issue with it you should probably discuss such with the court system that issues them. Or better yet, talk to the residents and businesses that are severely affected by aggressive panhandling.” Whyte’s office, which serves as a substation for The City’s Finest in the Central West End, had a bulletin board where the names of people with neighborhood orders of protection are posted. That way the private officers know whom to look for, emails obtained by ProPublica through a public record request show. Whyte recalled the case of a woman with chronic drug problems who he said was a persistent panhandler in the Central West End and who had been accused of petty theft. Neighborhood leaders sought to banish her after she created repeated problems. “We were seeking an order of protection against her because she didn’t live in the neighborhood, didn’t work in the neighborhood,” he said. “She had tallied up a number of incidents and police contacts.” He said the neighborhood never sought the orders “as an immediate action, it was always used as kind of, ‘Well, we have no other choice.’” In the fall of 2018, the clock had run out on neighborhood orders of protection against some people who had been banished from the Central West End. Whyte wrote to Richard Sykora, a lawyer for the city who was in charge of pursuing the orders in municipal court. “Many of our NOP’s have expired and unfortunately many of our problem people have returned to the CWE area,” Whyte wrote, adding, “We would appreciate you looking into obtaining NOP’s on the following subjects.” Whyte described one person as having “been observed buying narcotics” and another as having stolen a tip jar from a coffee shop. One was “mentally unstable” and “very disruptive at local businesses.” Another had repeatedly violated a previous neighborhood order of protection and, Whyte wrote, “continues to be a persistent panhandler.” Yet another, Whyte wrote, had been working with an organization that offers behavioral health services but he “has resumed aggressively panhandling.” Sykora wrote to Whyte a few days later saying he would seek new neighborhood orders of protection against most of the people Whyte had listed. In one case, Sykora told Whyte, the judge had made only half the neighborhood off-limits so the person could get to his job without breaking the law. Whyte told Sykora that he had checked with the employer and the defendant didn’t really work there. “Could we get the order modified?” he asked. Sykora did not respond to a request for comment. Whyte’s requests led to some of those people being banished again. They could be arrested on sight for setting foot in the 1.9-square-mile neighborhood. And some of them were. Whyte said the neighborhood has sought orders for people that were “running amok in the Central West End neighborhood. They wouldn’t heed any other warnings by the police, they wouldn’t conform, their behavior was antisocial.” “The reality is they don’t go to other neighborhoods” after being ordered to stay out of the Central West End, he said. “They don’t care about the order of protection.” Whyte said that since in-person court hearings have stopped, the neighborhood had hired a homeless outreach coordinator to try to address vagrancy in the neighborhood. One person the neighborhood has banished was Lorse Weatherspoon, a homeless man with a history of petty crimes. He was arrested in the Central West End in 2018 on suspicion of trespassing and burglary after a private policing company posted a $250 reward for his arrest. It isn’t clear what happened with those charges, but the city charged him with five violations of his ban from entering the neighborhood. “Lorse Weatherspoon was responsible for a crime a night,” said Jim Dwyer, chairman of one of the Central West End business districts that hires private police. Whyte said residents would send him surveillance video of prowlers, “And I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s Lorse Weatherspoon trying to see if he can get a bike out of your garage or steal your lawn mower.’” Neil Barron, Weatherspoon’s lawyer, said the order was a “blatantly unconstitutional violation of a person’s right to freely travel.” “Think about all the money used on this,” he added. “Does it solve the problem? Does it make the community safer? Does it help Lorse Weatherspoon rehabilitate himself? No, it doesn’t.” Nevada's Board of Pharmacy has requested a stay and is planning to appeal a state district judge's decision to strike pot from Schedule I of the state's Uniform Controlled Substances Act upon finding the drug's designation unconstitutional.

The board argued in a motion to stay last week that the October ruling represents a "tectonic shift" in state law that impacts public safety. The October order weighed in on a constitutional amendment ballot measure from 2000 that legalized cannabis medicinally, with Clark County District Judge Joe Hardy Jr. finding that the amendment does acknowledge that cannabis has a medical use. In contrast, the Board of Pharmacy argues in its motion that the constitutional amendment is actually "arguably susceptible to two or more reasonable but inconsistent interpretations." Previously, the board unsuccessfully argued that the regulation should be allowed to stay because it had been in place for more than 20 years — in spite of legalization. Nevadans legalized cannabis for medical use in 1998, resulting in changes to the state constitution. The ACLU filed its original petition in April on behalf of the Cannabis Equity and Inclusion Community as well as Antoine Poole, who had been convicted of cannabis possession after legalization. The civil rights group claimed that the board's decision to keep the drug listed as Schedule I was unlawful. Judge Hardy Jr. also rejected the idea that the board had authority to regulate cannabis, noting that a regulatory scheme for cannabis codified in Title 56 does not even mention the board. Sadmira Ramic, an ACLU attorney on the case, told Law360 on Thursday that "we are currently working on a response to their motion to stay the judgment and order pending appeal." Brett Kandt, general counsel for the pharmacy board, said the group has no comment at this time. In a statement Tuesday, ACLU of Nevada Executive Director Athar Haseebullah said "the board's continued support for criminalizing cannabis and continued representation of cannabis as more dangerous than fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamine raises serious questions of accountability and aptitude. The board's actions during the initial case alongside this appeal are a prime example of government overreach and should be offensive to every Nevadan." Judge Hardy Jr. previously noted that the board is required to review the schedule yearly and that to keep cannabis on the list runs afoul of the constitution. But the board argues that the October order should be subject to a stay pending its appeal. Questions of whether a conflict exists between the law and the board's authority are issues of first impression, the board contends. Poole and the Cannabis Equity and Inclusion Community are represented by Sadmira Ramic and Christopher Peterson of the ACLU of Nevada. The defendants are represented by Brett Kandt and Peter Keegan of the Nevada Board of Pharmacy. The case is Cannabis Equity and Inclusion Community et al. v. Nevada et al., case number A-22-851232-W, in the Eighth Judicial District Court, Clark County, Nevada. After numerous false starts, the Marihuana Regulation & Taxation Act (MRTA) was signed into law on March 31, 2021. Yet, almost two years later, there are still no legal sales of adult-use cannabis in New York. As we previously covered in these pages, the story of New York’s adult-use cannabis legalization is a long and tortured one. After numerous false starts, the Marihuana Regulation & Taxation Act (MRTA) was signed into law on March 31, 2021. Yet, almost two years later, there are still no legal sales of adult-use cannabis in New York. This, in turn, has led to a proliferation of unlicensed cannabis retail shops—euphemistically referred to as the “grey market”—even though §136 of the MRTA refers to such untaxed cannabis as “illicit cannabis.” Recently, reports have circulated that a crackdown has begun in some parts of New York City on both trucks and “smoke shops” selling such illicit cannabis (leading to at least two arrest). The proposed adult-use regulations, published on Nov. 21, 2022, warn that the sale of such illicit cannabis may preclude the award or renewal of licenses. See Proposed Rule §120.12(a)(9) (License Denials).