|

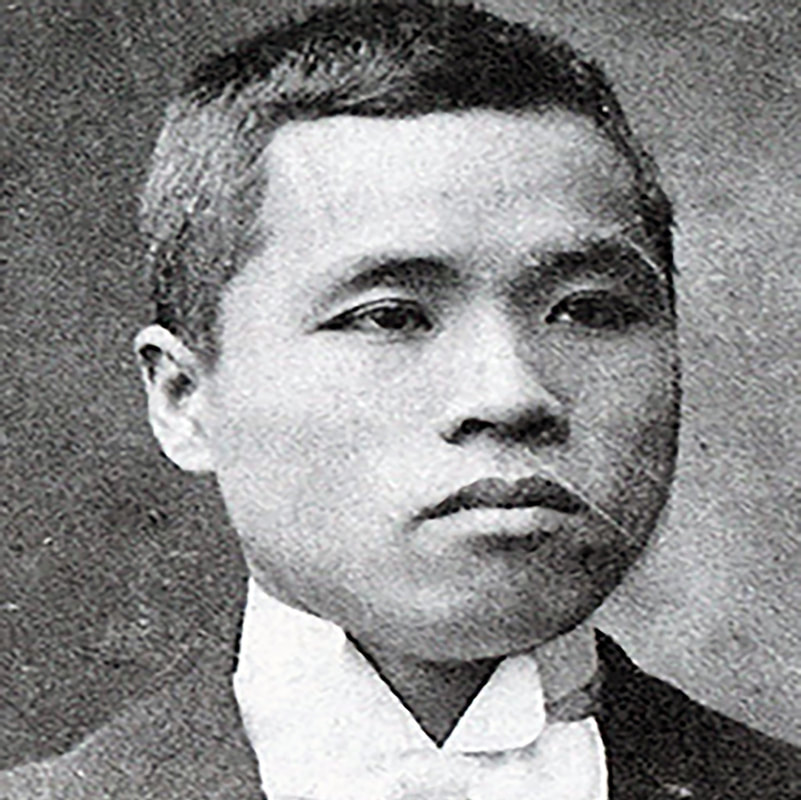

Takuji Yamashita earned his law degree from the University of Washington in 1902. He was awarded U.S. citizenship that year and then had it stripped away by the Washington Supreme Court because of his Japanese birth. The ruling also denied him admittance to the Bar, so Yamashita went into business and farming. He would later join a U.S. Supreme Court appeal to try to reverse the ban on Asian immigrants. FAMILIES TRAMPLED FLOWERBEDS for the best view. Youngsters perched on roofs. An Army band pumped out The Star-Spangled Banner, then explosions cracked the sky over Elliott Bay.

“One of the most magnificent pyrotechnic displays ever seen,” gushed The Seattle Times. It was July 4, 1907, and the instigators were as striking as the incendiaries. Seattle’s Japanese community had won hosting honors to dazzle the city with “Oriental” fireworks unloaded from the NYK freighter in the harbor below. The gunpowder came with an agenda. Before bombs burst in air, the immigrants sent their best orator to the stage. Born in a remote Japanese fishing village, Takuji Yamashita had sailed through law school in Seattle only to be blocked from becoming a U.S. citizen and practicing law. Now, on Independence Day, he delivered a speech so radical for 1907, it made the next day’s papers. People from Asia, Yamashita declared, could bring prosperity to places like Seattle — but only if Americans dealt them in as equals. “You have a great duty to elevate others to the same plane as yourselves,” he told the crowd, as quoted in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Let nobody in this country be denied right and justice.” Yamashita’s words soon faded like fireworks in the sky, but the long-forgotten Northwesterner — and the civil-rights movement in which he took part — cries out for a fresh look in a time of reckoning on race. Yamashita and his allies waged key battles against the creed that whiteness makes an American. WHEN YAMASHITA WAS born in 1874, Japan was shaking off centuries of isolation. Emigration was legalized the year he turned 12. When he was 14, Christian missionaries opened a church in his town, Yawatahama. After graduating from the prefecture’s most rigorous high school in 1893, he wrote his parents a letter promising to “try to walk the path of honor” across the sea. Snow-capped Mount Rainier, Fuji’s brawny American cousin, welcomed Yamashita to the Northwest. The 19-year-old waited tables at a countryman’s greasy spoon in Tacoma, slept at the Japanese Baptist Mission and raced through Tacoma High with top grades in everything but spelling. Next came the University of Washington’s new law school in downtown Seattle. Around a potbelly stove, students reviewed cases under the famously stern eye of Dean John Condon. The yearbook dubbed Yamashita a “Stranger in a Strange Land” but also declared him the star of the school’s moot court. At a banquet after passing the 1902 Bar exam, Yamashita titled his speech “The Making of an American.” That was premature. CONGRESS HAD LAID a path to citizenship in 1790 to any “free white person.” After the Civil War, it added people of African birth or descent. Yamashita clearly was not African, but what was a “free white person?” Judges ruled with wild inconsistency on aspiring Americans from Syria, Mexico and other non-European locales. By the time Yamashita came ashore, a federal judge had turned thumbs down to Shebato Saito of Japan, but some local judges still accepted Saito’s countrymen. This muddle prevailed on May 14, 1902, when Yamashita left the Pierce County Courthouse holding his naturalization certificate. He needed it — U.S. citizenship was a requirement for practicing law — and he got the right judge to sign it: an ex-lawyer for a railroad that was bringing in workers from Japan by the hundreds. But the state Supreme Court, gatekeepers to the Bar, held up Yamashita’s admission. State Attorney General W.B. Stratton declared that the young graduate’s Asian origins disqualified him. Yamashita fought back with the Declaration of Independence, arguing in a memorable brief that to reject a person of good character because of race would affront the core values of “the most enlightened and liberty-loving nation of them all … in which all men are equal in rights and opportunities.” “Worn-out Star-Spangled Banner orations,” Stratton responded, did not make Yamashita a member of the white race. The five justices nullified Yamashita’s citizenship, ending his legal career before it began. THREE MONTHS LATER, Yamashita posed in a studio next to his new bride, Ito Nakagawa, a grain trader’s daughter from his hometown. The newlyweds presided over the Klondike Hotel, one of 60 boardinghouses in Seattle’s Japantown — a northern slice of today’s Chinatown International District — a neighborhood thrumming with 18 tailor shops, three banks, two daily papers in Japanese and a baseball team. Yamashita had stature here. He presided over a debating society of educated Japanese people and founded an Ehime immigrants association that survives today. From time to time, he welcomed Japanese delegates planning the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, the 1909 World’s Fair that would proclaim Seattle the nexus of the frozen North and exotic East. In June 1907, workers broke ground for the fair’s Japanese Village, homage to a rising power whose cultural curiosities were all the rage. When The Seattle Times encountered a touring sumo wrestler that spring, it reported with wonder that, “He eats most of the time he is not drinking.” Beyond the titillation lay superhuman menace. “A Japanese coolie,” declared The Argus, a Seattle weekly newspaper, “can live on wages on which a white man would starve to death.” Racial tropes (such as the use of the word “coolie,” a now-outdated and offensive term for unskilled laborers) crossed with abandon: the Japanese worked like machines and wallowed in an opium haze; their homeland was a primitive backwater and threatened world domination; they were incapable of assimilating and unwilling to do so. Through this fog of fear and fascination sailed NYK’s Shinano Maru, bearing fireworks for Seattle’s 1907 Fourth of July. More than 10,000 spectators, according to The Post-Intelligencer, gathered for the patriotic show near today’s Kerry Park on Queen Anne Hill. That crowd count might be inflated, but photographers captured a sea of straw hats and bonnets. Seattle’s population had tripled in the decade since NYK (Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha) made the city its main U.S. port; Japan had helped build the Northwest. In his keynote address, Yamashita told the crowd this was just the beginning. “We hope to see this country prosper,” he proclaimed on behalf of his fellow Issei, or Japanese immigrants. “As it prospers, we prosper.” The Post-Intelligencer praised Yamashita’s words as “an answer to the agitators who perpetually preach the dangers of a Japanese peril,” but agitators held increasing sway. To appease them, President Theodore Roosevelt cut a deal that year with Tokyo: No more Japanese workers could come, but wives could join settlers already in the United States. The upshot: a Japanese-American baby boom. In Seattle’s Japantown, four midwives sprang into duty night and day. Because a child born on U.S. soil is a citizen by birthright, Japanese immigrants were having baby Americans. Roosevelt’s deal drove agitators to a new level of rage. At the 1908 International Exclusion League convention in Seattle, an American Federation of Labor official declared that the Stars and Stripes would never have “a yellow streak.” WHEN THE CAMERA clicked on Independence Day 1913, Yamashita stood watching the parade with three fidgety children by his side. His growing family had moved to Bremerton, where the shipyard repaired vessels for the looming Great War. At the Yamashitas’ Togo Hotel, workers occupied all 12 rooms, and the storefront barber collected 35 cents a cut. Legal acumen was as crucial as filling beds. The Yamashitas ran the Togo through a corporation fronted by a pair of white Seattle lawyers. The state constitution barred noncitizens from owning land unless they “in good faith have declared their intention to become citizens of the United States.” Yamashita had famously declared that intention, only to see his citizenship stripped away. His brother Jirosaku — who arrived in 1905 with his wife and son — farmed berries in Pierce County, an area The Seattle Star said the Japanese were “overrunning.” Barred from owning land, Japanese people signed crop contracts for the right to wrestle white people’s stumps and swamps into productive farms. Fueling this Issei toil was the dream that birthright citizenship would lift their U.S.-born children, known as Nisei, to secure footing. But politicians kept planting new obstacles. In 1921, Washington state banned those ineligible for citizenship from holding land in the name of a minor. Citizenship no longer was a pass to the ballot box or a badge of belonging; it meant survival. Yet attempts to expand citizenship died at the hands of U.S. House Immigration Chairman Albert Johnson, a Tacoma Republican outspoken in his animosity toward Asians. The U.S. Supreme Court was the last hope, and a Honolulu immigrant named Takao Ozawa — an educated businessman, like Yamashita — was hellbent to get there. Ozawa liked to cite Revolutionary War turncoat Benedict Arnold to prove that patriotism had nothing to do with ethnicity. Arnold’s name sounded American, but he had proved a traitor. Ozawa’s name might sound foreign, he told a judge, but, “At heart, I am a true American.” Coming decades before Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to judge people by character rather than color, Ozawa’s parable failed to persuade a superior court, a federal district court or the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. But with alien land laws spreading, Issei leaders agreed to take Ozawa’s case to the top. Yamashita joined as a backup. Because Washington’s highest court had already rejected his citizenship, his appeal would speed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. To activate the maneuver, Yamashita and a Montana railroad man named Charles Hyosaburo Kono created a paper company called the Japanese American Real Estate Corp. — its very name thumbing its nose at Washington’s alien land law. As expected, Washington’s Secretary of State J. Grant Hinkle blocked the corporation, and the state Supreme Court backed him up, citing its old ruling against Yamashita. The U.S. Supreme Court quickly paired the case with Ozawa’s. Victory in the twin cases would pry open a portal to the American dream. Defeat would seal barriers that had been, at times, semipermeable. To borrow from baseball — a sport beloved in Yamashita’s native and adopted lands — Japanese immigrants had been trying to get ahead one base at a time, only to keep losing. Now, their leaders concluded, it was time to swing for the fences. They should have checked the umpires. On Oct. 3, 1922, newly seated Chief Justice William Howard Taft presided over oral arguments in the U.S. Supreme Court. His court would spend the 1920s thwarting a minimum wage, integrated schools and other progressive ideas. But first, it would decide whether Japanese people could become Americans. Forsaking Yamashita’s rights rhetoric of 1902, the Japanese legal team tried science. In an attempt to puncture the law’s arbitrary racial boundaries, treatises traced Caucasian origins in the Ainu people of northern Japan, and found that Japanese individuals could be “whiter than the average Italian.” Science did not sway the court. Justice George Sutherland — an immigrant from England — wrote in the unanimous opinion that individuals’ skin color might vary, but Japanese people were “clearly of a race which is not Caucasian.” The rulings made Asian exclusion explicit. Japanese immigrants had struck out. BACK IN BREMERTON, Yamashita had other problems. Shipyard jobs had sunk to half their wartime peak, forcing him to shutter his boardinghouse. And by 1926, he and Ito had endured the deaths of five of their seven children, from meningitis, tuberculosis and other menaces of the era. The two surviving children grew up on separate shores. Haruko, raised by relatives back in Yawatahama, would bear nine children there. Martha, the family’s American-born citizen, would bounce from the Bremerton High glee club to a stint at UW to her parents’ latest venture: farming. In a lagoon where Dyes Inlet touches the town of Silverdale, the Yamashitas planted oysters from Japan. Ashore they laid tight rows of strawberries almost up to the family’s front porch. Rounding out the scene were an enormous German shepherd, a skinny horse and streams of visiting family and friends. Around the firepit, these guests rarely heard Yamashita lament his hardships; he was more likely to be recruiting for a fishing trip. His framed law diploma, however, told its silent story on the living-room wall. AS THE FAMILY’S U.S. citizen, Martha signed the 1937 contract to purchase the Silverdale farm. The Yamashitas put $500 down, records show, and chipped away at the $2,000 balance with each harvest. They had whittled it down to $1,500 by Dec. 7, 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. President Franklin Roosevelt soon banished everyone of Japanese descent from the West Coast. Soldiers cleared out Bainbridge in March, Seattle in April and Kitsap in May. Facing exile, the Yamashitas deeded their farm back to the seller, who sold it to a white family two years later for $16,000. The Yamashitas spent the next three years at War Relocation Centers — historians call them concentration camps — in California and Idaho. At Tule Lake, Takuji Yamashita swore a loyalty oath to the United States. At Manzanar, he was treated for a heart ailment. At Minidoka, he turned 70; weighed in at 110 pounds; and logged 1,666 hours on the laundry, coal and maintenance crews. When Takuji and Ito Yamashita left Minidoka on May 17, 1945, they moved in as helpers to a white widow in West Seattle, according to relatives and War Relocation Authority records. From the living-room window, they could gaze across Puget Sound and almost see their old farm. If Yamashita was bitter, he did not admit it. “I spend my days in joy and appreciation,” he wrote for a postwar Japanese Baptist Church event. Only one thing could break his spirit. When daughter Martha died of tuberculosis in 1957, Takuji and Ito packed the law diploma and photo albums onto a plane for Japan. In the town of his birth, Takuji Yamashita died on March 18, 1959. It would take him another 42 years to gain admission to the state Bar. CONGRESS ENDED RACE-BASED naturalization in 1952. Washington voters repealed the Alien Land Law in 1966. In the 1980s, America sent $20,000 checks to those it had locked up in WWII camps. By the millennial year of 2000, schoolchildren poked around the desolate camps on field trips. Gary Locke, the grandson of peasants from Guangdong, China, inhabited the Washington governor’s mansion. A Japanese citizen, Ichiro, had signed with the Mariners and was about to become the most popular human being in Seattle. And the UW law school decided to celebrate its centennial by honoring its thwarted early graduate. With the Asian Bar Association of Washington and the State Bar Association, the school petitioned the state Supreme Court to posthumously admit Yamashita to the Bar. The March 1, 2001, ceremony in Olympia would bring Yamashita’s descendants from Japan together with Northwest luminaries in law, trade, diplomacy and civil rights. Nature put one more hurdle in Yamashita’s way. The day before the event, the 6.8-magnitude Nisqually Earthquake rained plaster onto the pews of the Temple of Justice and shut down airports and highways. A fast-fingered travel agent rebooked flights. Two hundred guests found their way to an intact Tacoma courtroom offered by a federal judge. There, state Attorney General Christine Gregoire — successor to Yamashita’s persecutors of the same title — addressed Takuji Yamashita across time. “Today,” Gregoire said, “we can finally say you won.” Yet to come were the Sept. 11 attacks, President Donald Trump’s Muslim ban, family separations, the Wall, Black Lives Matter, and a spate of pandemic-era hate crimes against Asian Americans. As those events show, citizenship can’t right every wrong. But in standing up to the injustices of his day, Yamashita voiced with rare clarity why America must improve — to live up to its own founding principles. His writings and speeches belong in U.S. history texts, beacons to the future as well as the past. Experts debate whether the legal battles waged by Yamashita and his allies advanced their cause or set it back. But for 20 years, a University of Washington scholarship bearing Yamashita’s name has supported law students who promise to devote their careers to human rights.

0 Comments

Lawsuits to settle allegations of misconduct by more than 7,600 officers from around the country have amounted to more than $3.2 billion over the past decade. The alleged misconduct led to nearly 40,000 payouts to resolve lawsuits and claims of wrongdoing at 25 of the nation’s largest police and sheriff’s departments between 2010 and 2020. More than 1,200 officers in the departments surveyed had been the subject of at least five payments; more than 200 had 10 or more.

In Chicago, for example, officers who were subject to more than one paid claim accounted for more than $380 million of the nearly $528 million in payments in that city. The typical payout for cases involving officers with multiple claims — ranging from illegal search and seizure to use of excessive force — was $10,000 higher than those involving other officers. Few cities or counties track claims by the names of the officers involved — meaning that officials may be unaware of officers whose alleged misconduct is repeatedly costing taxpayers. While multi-million dollar settlements regarding allegations of police misconduct often generate headlines, the median amount of the payments is $17,500, and most cases are resolved with little or no publicity. New York, Chicago and Los Angeles accounted for the bulk of the overall payments documented at more than $2.5 billion. States and local governments have long contracted with private prisons as a way to outsource carceral needs to cheaper sources of labor. As a result, for-profit prison companies in the U.S. have emerged as a powerful political voice and exerted an influence that has distorted justice systems across the country, according to an Ohio State University Legal Studies Research Paper. The paper’s author, Amy Pratt, a student at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, warns that if the influence of private prisons isn’t curbed, sentence lengths will continue to increase, mass incarceration will balloon, and judicial integrity will be in jeopardy. “This voice is unnecessary and should not exist,” she writes in the paper, posted under the auspices of the Drug Enforcement and Policy Center. “Private prison companies are not the officials who are elected to write sentencing laws or to hand out sentences in a courtroom. They should have no say in the process, whether that say is intentional or not.” Private prisons have steadily grown in influence and strength over the past two decades. According to the Sentencing Project, some 115,428 individuals were held in for-profit facilities in 2019, representing 8 percent of the total state and federal prison population, an increase of 32 percent since 2020. Data compiled by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and interviews with corrections officials reveal that in 2019, 30 states and the federal government incarcerated people in private facilities run by corporations including GEO Group, Core Civic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America), LaSalle Corrections, and Management and Training Corporation. Longer Sentences Pratt asserts that the sheer existence of private prisons in a jurisdiction can lead to longer sentence lengths. She cites a study conducted by researchers at UCLA, sentence length increased by an average of 23 days after the opening of a private prison, she details in her report. Another study cited by Pratt found that doubling private prison capacities in a state increased sentence lengths in that state’s courts by 1.3 percent, or 18 days, compared to sentence lengths given out by adjacent courts in other states. That study’s authors found that the longest sentences are handed down in states where private prisons offer the largest cost-savings compared to public prisons. But, the attraction of a “cheap high-quality private prison” is a fallacy, Pratt writes. Private prisons are often staffed poorly in comparison to public prisons, and guards in private institutions usually receive less training and less pay to their public counterparts — illuminating the real reasons why private prisons are less expensive upfront, said Pratt. She added that private prisons often end up costing the government more in the long-run than what was saved in the short-run compared to the costs of public prisons. “Because private prisons have higher recidivism rates than public prisons, the short-term cost-savings from the original contract are offset by the long-term costs for the state of dealing with recidivism,” the paper asserted. Follow the Money Private prison companies have been able to drive harsher sentencing laws and policies because of their steep campaign contributions to state and federal politicians, according to the paper. Since 2000, Pratt details that private prison companies have given over $6 million to politicians — particularly those who favor tough on crime policies that fill prisons and are more likely to accept private sector prison takeovers, many of them Republican legislators. These contributions give private prison corporations access to lawmakers who would be willing to pass favorable legislation for them, Pratt explains. During the 2020 election cycle, GEO’s founder contributed $500,000 to Republican campaigns, but just $10,000 dollars to Democrats. Pratt acknowledges that both blue and red states utilize private prisons, and “it’s not an issue that can be solved by electing one party over another.” Moreover, Pratt writes that some private prison companies have even donated to the campaigns of judges in state elections, directly influencing who is elected and what type of policies are enacted. And, if a judge knows a prison is at or near capacity, they might be more likely to give a shorter sentence when possible. But, Pratt writes, if the judge knows a private prison has room, they might be more likely to give a longer sentence that they feel their constituents or court demands. What’s worse, there is documented evidence of judges outright accepting bribes from private prison companies to give out harsher, longer prison sentences that keep beds full. “The influence is seemingly small for the most part, but it should not exist at all,” Pratt explains. “Private prison companies should have no voice in sentencing.” Suggested Solutions “The best solution to preventing private prisons companies from having a voice in sentencing law and policy is to stop using them entirely,” Pratt begins. “However, given their prevalence at the state and federal level, that solution is both unrealistic and unlikely.” While America’s system of private prisons has highlighted numerous injustices, France’s system of utilizing private prison companies shows a different value in aspects of their prison programs. “In France, all correctional services fall under the Ministry of Justice,” Pratt wrote, noting that because of the centralized management, elements of budget, control, and leadership are all still overseen by the government. Moreover, French sentencing law doesn’t have mandatory minimums, and judges are given discretion for maximum sentence — practices Pratt says America could take note from. “The goal of the [French] criminal justice system is rehabilitation, and so incarceration is only viewed as a means to that end, instead of the end itself,” Pratt explains. “This hybrid model makes prisons more expensive, but provides higher quality services to the inmates in them.” Other suggested solutions include:

The full paper is below Andrea Cipriano is Associate Editor of The Crime Report. Katherine Lucero — a daughter of farmworkers and a longtime juvenile court judge who calls for compassion and support rather than jail and foster care — is now leading the most populous state toward a once-unimaginable goal: a future without youth prisons.

In a historic shift aimed at reversing decades of poor outcomes for youth offenders and public safety, California is closing its Division of Juvenile Justice. Now it’s the job of former Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Lucero, that court’s first appointed Latina judge, to smooth the transition from punishment to a more therapeutic approach. Her new title is director of the newly minted Office of Youth and Community Restoration, an agency that is not located within the sprawling corrections system, but rather, the state’s health and human services agency. “She is flat out one of the bright lights in California’s judiciary,” said retired Santa Clara County Judge Leonard Edwards, who hired Lucero to be a dependency court commissioner more than 20 years ago. The former prosecutor went on to succeed Edwards as supervising judge in 2006. “She’s a terrific leader who knows how to get off the bench and into the community, how to bring people together to work on issues.” When the state sought her leadership to oversee the re-envisioned California youth justice system, Lucero, 60, said the opportunity made sense. She calls the “over-incarceration of Black, brown and Native youth” something that justice system leaders can’t be afraid to tackle in a more substantive way. She urges “creative” approaches in handling the cases of youthful offenders, who come from “the least-resourced neighborhoods, where schools no longer have mental health counselors, sports, art, drama or librarians.” In a recent interview with The Imprint, Lucero said she was “very taken with the idea of closing the statewide youth prison system and then realigning the care of our youth back to their communities, where they have homes and families, lifelong friendships. Who wouldn’t want to be part of this major undertaking?” Changing the Culture She described shifting state control to counties as part of a larger culture change: “Treating youth as people, not as criminals who should be punished for all time.” Law enforcement’s response to the change has been measured, as probation departments face growing responsibility to house and supervise those young people the state has deemed most dangerous. The Chief Probation Officers of California, along with the California State Association of Counties and several other agencies strongly opposed shutting down the state juvenile division, calling an early proposal “unworkable.” An August 2020 joint memo stated that the creation of an “untested state bureaucracy” would divert “critical funding away from direct services to youth.” These days, county probation leaders say the new office has an important role to play. Chief Probation Officers of California Executive Director Karen Pank said in an emailed statement that her members “welcome the state maximizing its resources and providing help such as technical assistance where there are current gaps.” Pank also said counties will look to the state office for “their expertise to enhance our ability to meet the needs of youth and make this policy change safe and successful.” But the pleas for fundamental change continue, as was evident at a recent rally in downtown Los Angeles. Dozens of youth advocates chanted and waved signs in support of legislation that would provide a bill of rights to teens held in juvenile detention facilities. In addition to providing technical assistance to counties, Lucero’s new agency will be responsible for investigating complaints, resolving them and producing and publishing regular reports to the Legislature. To that end, the office will soon hire the state’s first-ever youth justice ombudsperson. For young people like Mialissa Flores, who have spent time behind bars, outside scrutiny of conditions inside detention facilities is long overdue. Flores, who was first detained at San Diego County’s juvenile hall at age 13, said she wants the new official leading the Office of Youth and Community Restoration to address the grievances of incarcerated young people, and to uphold basic standards of care inside lockups. Now 21, Flores said that during several stints in juvenile hall, she wasn’t even given warm enough clothes or basic hygiene products. And probation officers minding her didn’t seem to care about her well-being. “We need somebody who knows that these are children, that they’re growing, developing and going through puberty in a juvenile hall,” Flores said. “They’ve made mistakes but they shouldn’t be treated like animals.” The state’s new Office of Youth and Community Restoration was created in 2020 by Senate Bill 823, which maps out the shuttering of the long-troubled youth prison system, once known as the California Youth Authority and more recently as the Division of Juvenile Justice. The new statewide office will no longer be a part of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. As part of a fundamental shift in how the state now views its young charges, it is now placed under the California Health and Human Services Agency. Lucero calls that “a huge signal to our communities that we see youth as a different kind of law violator than we do adults.” The Value of Intervention Sue Burrell, policy and training director with the nonprofit Pacific Juvenile Defender Center, said Lucero and her office will be crucial to realizing the transformation envisioned under SB 823 — a premise that most youth who commit crimes are in need of treatment for trauma, that their lives have value, and they can return safely to society if given some investment of education and therapeutic intervention. The Office of Youth and Community Restoration will collect data, monitor grievances through a new ombudsperson, administer grants and advise counties on appropriate programming and services that better support youth and reduce recidivism. “This is the moment that can make or break a long history of thinking that we can put youth in institutions to make them better,” Burrell said. She also noted the instrumental role Lucero will now play: “I’m hoping that she will embrace the intent and the spirit of the new law and make sure that she doesn’t just replace one big state institutional system with 58 small ones.” Burrell is among those longtime youth justice advocates who have spent decades fighting once-Dickensian conditions inside state facilities: youth confined to isolation cells for 23 hours a day, violent treatment by staff, and school and recreation provided to youth in structures that were literally cages. Now, despite the hope of these justice reformers, there are concerns that there may soon be not just a handful of facilities to monitor for fair treatment, but scores of them. Will Lucero’s office be up to the task? The office got off to a contentious start last year, when Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration set aside an annual $3 million and 19 positions in his initial budget ask. That alarmed advocates who said that was far too little for the office to do an adequate job overseeing 58 county-run juvenile justice systems. Although Newsom eventually provided a one-time influx of about $28 million in start-up funding to the agency’s coffers and increased the number of staffers to 33, there are still concerns about whether it has sufficient enforcement authority. In an interview, California Assemblymember Mark Stone (D) said he remains concerned that youth in some parts of the state will miss out on the reforms if Lucero’s office can’t hold counties to a common set of standards, standardizing rehabilitative offerings for all state residents. Like other justice-watchers, he worries that the quality of youth justice in California could soon amount to simple geography — those in the progressive Bay Area will receive counseling and have opportunities to garden and learn a trade, while in the more tough-on-crime Central Valley counties, the same kid who committed the same crime might simply be locked away in a juvenile hall cell, with scant opportunity to remake themselves. “We’ve thrown a bunch of money at them and then are kind of washing our hands of accountability and results,” Stone said of the state’s counties. “And to me, that’s very dangerous when we’re dealing with kids and their futures.” Healing Families, Not Just Kids Lucero began her career as a deputy district attorney. Beginning as judicial officer in 2000, she went on to lead the San Jose-based child dependency division, and later supervising and presiding judge of its juvenile justice court. Lucero left her mark in the South Bay with her support for the creation of specialty courts that approach families with a less punitive and more therapeutic approach. Her courtrooms were named Girls Court, Zero to Three Dependency Drug Treatment Court, and Family Wellness Court — aiming for more lasting solutions to people’s problems. Instead of lawyers facing off in court, clients were offered mental health care, housing opportunities and a team approach to stabilizing their lives. Throughout, she brought lessons from her background to bear. Lucero is a rare judicial officer who openly shares her personal history. In a video posted on the Santa Clara County courts website, she sits at her desk, her shiny black hair gathered in a bun much like the Frida Kahlo portrait on the wall behind her. To handle the pressures of her work, Lucero and her husband of 30 years practice yoga on most mornings. She said she also relies on “strong mentors,” who she stays connected with throughout the week and who remind her “that I do not have to tackle difficult problems on my own.” Lucero has two adult daughters — one is a comedic actress and a yoga instructor, and another is an attorney. “They are both amazing in every way,” she said. Lucero’s childhood had struggles. She describes growing up with a father who was an “active alcoholic” until she was 15, and identifying with the families she sees before her in the dependency and delinquency courtrooms. Because of her experience, however, she also knows about transformation. “I grew up in a household that looked very similar to the households that I saw in juvenile dependency court,” Lucero says in the video. But her father stopped drinking when she was a teenager. “I saw him get better, and I saw my family heal,” she said. “I got to see my dad become a man of great respect in our community.” From the bench, Lucero fought for more time on cases, pushing the courts to better evaluate critical turning points for children who were often rushed through dockets like goods on a conveyor belt. Early in her juvenile court career, she tackled the sheer volume of cases, and the impact on vulnerable families’ lives. Among the most life-changing courtroom scenes were the “detention” hearings in dependency court, where judges decide whether a child can live with parents or must enter foster care. With overloaded calendars and high caseloads, often a family’s fate was determined in mere minutes. Lucero changed court schedules so parents and lawyers could meet in the mornings before hearings, “giving families the time they needed and deserved,” she said. Family “engagement rooms” were set up to keep youth and parents connected “even through the struggle” of foster care separation. Afternoon hearings were allotted a full 30 minutes, which, in 2006, was considered a lot of time to discuss matters as serious as whether a teenager would go to a group home, or whether a parent’s custody rights should be permanently terminated. When decisions like that were being made, she said: “We just wanted to be very thoughtful.” Juvenile Justice Goes Local California’s juvenile justice system is in the middle of a seismic shift that Lucero will now lead. In the years leading up to the Division of Juvenile Justice shutting down, the number of youth ages 12 to 25 locked up by the state has dropped almost unimaginably — from an average daily population of roughly 10,000 in 1996 to fewer than 700 last year. As of July 1, the state no longer accepts most new commitments, and its four remaining prisons will be closed by June 30, 2023. Local juvenile halls, which house minors awaiting trial or serving time for less serious offenses, have also seen huge drops in population. In 2002, California counties housed an average of 11,124 youth a day in their juvenile detention facilities. In 2021, that number fell to 2,162, according to state figures. All 58 counties met the Jan. 1 deadline for turning in their “realignment” plans to house even those youth who have committed the most serious and violent offenses in local facilities, Lucero said. And they’re slated to receive $100 million by the state to spend on local capacity. But a reading of the details shows a patchwork of approaches, not all of which are fully in sync with Lucero’s vision. Progressive Santa Cruz County plans to use almost $1 million on its transition, investing in approaches that correct racial injustice, and purchasing a bus and digital devices to make sure family members can visit and stay in touch with incarcerated youth. But in more conservative Kern County — which had 45 youth in state custody as of January 2021 — the plan is a tougher approach. Kern county will use $12.5 million to house its most serious offenders in a pod in the 120-bed Kern Crossroads facility, where correctional officers are trained in “de-escalation techniques as well as Crisis Prevention Intervention and defensive tactics.” Kern County’s plan states that “youth will be held accountable for misbehavior but also provided with an opportunity to redirect their negative behavior.” Back On Their Paths Despite heel-dragging in some regions of the state, the changes underway in California juvenile justice are a significant departure from the past. Besides shutting down its youth prisons, the state now prohibits children aged 15 and under from being tried as adults, no matter the crime. “Looking at the brain science, we’re seeing that youth are incredibly resilient,” Lucero said. “And so we’re offering education more than just a surveillance model. We don’t just have to focus on one moment in time when you made a bad choice. “We have to ask not just ‘what did you do,’ but ‘what happened?’” In the 81 years since founding the Youth Authority in 1941, the state has locked up tens of thousands of juveniles considered too dangerous to remain in their homes and communities. Now, California is reversing course, teaching young people how to make amends for their actions through restorative justice, education and therapy so they can, as Lucero puts it, “get back on their paths.” It’s a model she says the nation would do well to follow. “I think we’re on to something,” she said. Illinois Scores Top Rank, Alaska is Lowest In the last 18 months, states have adopted a more “enlightened” approach to integrating formerly incarcerated individuals in civil society, in areas ranging from the restoration of voting rights to eliminating discrimination in hiring, according to a report by the Collateral Consequences Resource Center (CCRC). “But there is still a long way to go before people with a record are treated fairly in getting a job and supporting a family, securing a place to live, and participating fully in civic affairs,” writes CCRC Executive Director Margaret Love, a former U.S. Pardon Attorney, in the beginning to the report. A companion “report card” ranking all 50 states according to how well they measure up in nine different areas of reentry and reintegration gives Illinois the highest marks and places Alaska at the bottom. The report, entitled The Many Roads From Reentry to Reintegration, notes that the trend towards a fairer and more understanding treatment of individuals with criminal records has accelerated. Several new states have joined those previously identified as reform leaders, and half a dozen other states have made “substantial improvements” to existing laws, according to the report. The survey and report card are the latest in a regular series of evaluations of progress in the nation’s restorative rights laws, produced by CCRC. Many of the latest improvements were driven by economic necessity, the CCRC said, noting that the pandemic has driven home the concept that communities need to “support, train, and recruit workers who are essential to rebuilding the small businesses that are the lifeblood of healthy communities while supporting themselves and their families.” To do this, states have broadened the occupational and professional licensing requirements to allow certain criminal records to not impact someone’s ability to further themselves and ensure non-discrimination while hiring. Many states however are still lagging behind in restoring civil rights, and removing barriers that impede the formerly incarcerated from full participation in society. “Like criminal sentences themselves, [collateral consequences] should be imposed only when and to the extent necessary, there should be opportunities for case-by-case consideration, and there should be an end to them,” the report notes. “Otherwise, collateral consequences, designed to promote public safety, risk undermining it.” The Report Card Within the Reintegration Report Card ranking, scores were calculated by assigning grades A-1 through F-5 and adding up the nine columns of laws (like voting, pardon relief, employment opportunities, etc.) and then assigning an overall ranking for each state. Take Alaska, for example, which the report ranks as the lowest-performing state in terms of nearly every law category analyzed — receiving “F” grades for pardoning, felony relief, misdemeanor relief, certificates of relief, employment, and occupational licensing laws. “Alaska is one of the very few states that has no general law regulating consideration of criminal records by employers or occupational licensing agencies,” Love writes. “Alaska has enacted no laws in recent years in furtherance of reentry or reintegration, and its overall restoration scheme remains one of the two most restrictive in the Nation. Exactly in the middle of the pack is Missouri, which was ranked as 25/50 for its generally high ratings with an “A” grade for deferred adjudication, and “B” grades for occupational licensing access and pardoning — but poor ratings for every other law variable, garnering an “F” in Certificates of Relief.” “Missouri rose five places in the rankings this year by virtue of its improved record relief laws and it’s governing pardoning,” Love details, noting that it could rise high by broadening individual eligibility for record clearing and employment. After ranking highly in all nine areas of reentry and reform, Illinois continues to hold its place at the top of the ranking, specifically because of the fact that Illinois has taken action to address discrimination based on conviction records with its Human Rights Act. “Illinois has taken several commendable legislative steps to encourage voting awareness by prisoners, but it seems that it would take a constitutional amendment to do away with felony disenfranchisement altogether,” the report details. With that, like all states, Illinois still has room to improve and could eliminate some of the access to barriers regarding petition-based relief that was identified in last year’s CCRC report card, including giving courts broader authority to defer adjudication of cases eligible for probationary sentencing to avoid conviction. Washington D.C. is noted in this year’s report card as having skyrocketed from 40th place to 19th place, thanks to enacting comprehensive occupational licensing laws in 2021, complementing its existing strong law regulations of criminal record employment regarding housing. To that end, the District of Columbia’s laws are “among the least generous in the Nation” due to the fact that there is no relief for felony convictions, and the president has granted only a handful of pardons in D.C. in the past 50 years. “We hope our grades will challenge, encourage, and inspire additional reforms in the months and years ahead,” the report concludes. Margaret Colgate Love is a former U.S. Pardon Attorney and current Executive Director of the CCRC. Love represents applicants for executive clemency in her private practice in Washington, D.C. She is also the lead co-author of Collateral Consequences of Criminal Conviction: Law, Policy & Practice, and created and regularly updates the Restoration of Rights Project database. See Below for the Full Report Andrea Cipriano is the Associate Editor of The Crime Report While legislators and judicial officials have been vocal in their commitment to combat trafficking in persons, many well-intentioned policies fail to translate into practice.

For example, U.S. Attorney General Merrick B. Garland last month announced the Justice Department’s new National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking, which includes a provision to develop and implement new victim-screening protocols to identify potential human trafficking victims during law enforcement operations, and encourage victims to share important information. However, he doesn’t adequately explain how these will be developed, tested, or enforced. While the AG’s new strategy sounds good, we fear it may not have practical benefits for victims, considering that extant screening protocols are limited in efficacy. Examples of where this type of general strategy has fallen short in the past are easy to find. A trafficking survivor recently filed a lawsuit against Fairfax County Police in Virginia, claiming that from 2010 to 2015 the police allowed sex traffickers to operate in exchange for free sexual services in a coverup that reached all the way to the then-chief of police. Her allegations are partially corroborated by former detective Bill Woolf, who was assigned to work on the Northern Virginia Human Trafficking Task Force at that time. There plenty of other examples of the impunity enjoyed by traffickers and poor treatment from law enforcement that can be experienced by victims of trafficking. On Aug. 21, 2015, one of us (Mehlman-Orozco) was driving in front of Springfield Mall in Fairfax County, Virginia, when she saw a black sedan, with out-of-state license plates, pull over to the side of the road. The driver exited the vehicle, walked to the passenger side, and removed a blonde woman from the passenger seat and began throwing luggage at her, before driving off. Mehlman-Orozco pulled over to help the woman, who she later learned was a victim of sex trafficking—Jennifer Lowery-Keith. [This account was earlier described in an article in The Hill.] Lowery-Keith, the co-author of this essay, was traveling to Virginia from Connecticut with her trafficker, who was out of jail on pretrial release for a malicious wounding charge against one of his other victims. She had been sex-trafficked on and off for nearly 15 years, and at one time was even shot at point-blank range in the leg, requiring emergency surgery and vascular transfusion. After learning that Lowery-Keith was a trafficking victim, Mehlman-Orozco reported this incident to Fairfax County Police Detective Bill Woolf, whom she knew from anti-trafficking conferences. Det. Woolf helped get Jennifer into residential treatment and collected information about her trafficker, who even had a forthcoming court date for the malicious wounding case against another one of his sex trafficking victims. However, that charge against the trafficker was null prosecuted because the victim in that case went missing and no charges were ever levied against the trafficker for how he exploited her and physically abused her. Neither Mehlman-Orozco nor Lowery-Keith were told why no charges were filed against the sex trafficker, but the allegations that are now pending civil court against Fairfax County Police may provide a potential explanation. Lowery-Keith is rebuilding her life and has even started writing about her experiences as a human trafficking survivor. But she doesn’t feel that justice was served. When she mustered the courage to call the police on her trafficker, after he threatened to kill her children, she was arrested, not him. And although Jennifer didn’t personally witness or experience commercial sex exchanges with law enforcement, she certainly heard stories of these exchanges being commonplace across multiple states. ‘Disheartening Reality’ Unfortunately, the pending civil case in Fairfax County may be exposing a disheartening reality: Victims of trafficking often continue to be denied justice, erroneously criminalized, and/or sexually harassed by criminal justice officials who are meant to protect them. Allegations against law enforcement for sexual abuse and/or exploitation of sex trafficking victims and sex workers can be found across the country; for example, in Maryland, New York, Kentucky, California, Nevada, Connecticut, and Georgia. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why trafficking crimes are significantly under-reported—although non-profits estimate hundreds of thousands of trafficking victims in the United States, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report there were only 562 arrests for sex trafficking and 146 arrests for labor trafficking in 2019. If the non-profit estimates are true, this means that fewer than 1 percent of traffickers are arrested for their crimes. Regardless of whether Fairfax County is found liable for the allegations contained in the pending lawsuit, this case should draw attention to the treatment of trafficking victims by the criminal justice system across the county. Juveniles should not be arrested for prostitution, law enforcement officials should not be accused of receiving commercial sex services in exchange for impunity, and traffickers should not face minimal punishment for modern slavery. The strategy announced by AG Garland is a step along the way, but it’s nowhere near sufficient. It’s time for a national strategy that includes specific actions to significantly increase exploitation identification, as well as protect victims from erroneous criminalization and revictimization. No victim of trafficking should ever fear reporting their exploitation to police, but the stories of survivors remind us that this is the lived reality for many. Jennifer Lowery-Keith is a sex trafficking survivor, author, anti-trafficking advocate, and public speaker on human trafficking. Kimberly Mehlman-Orozco holds a Ph.D. in Criminology, Law and Society and serves a human trafficking expert witness in criminal and civil court. Her first book Hidden in Plain Sight: America’s Slaves of the New Millennium is used to train law enforcement on human trafficking investigations. While the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have recently proposed new guidelines that would ease restrictions on prescription opioids, aiming to give millions of Americans suffering intractable and chronic pain better access to the opioid painkillers, both physicians and addiction experts predict that few governors or lawmakers will be eager to loosen restrictions during an ongoing overdose epidemic, reports Pew Stateline.

Initial CDC guidelines recommended that doctors limit initial prescriptions of opioid painkillers to no more than a week and set a maximum daily dose that is roughly equal to 90 mg of morphine, while also stressing that starting any new patients on the highly addictive painkillers should be a last resort. The new guidelines would give doctors wide discretion to weigh the benefits of pain relief and improved physical function against the known risks of opioid painkillers, while also setting no limits on dosage. The CDC stresses that physicians should never abandon patients who seek higher doses or longer use of painkillers than the existing recommendations, noting that doing so is contributing to “patient harm, including untreated and undertreated pain, serious withdrawal symptoms, worsening pain outcomes, psychological distress, overdose, and suicidal ideation and behavior.” In response, a few states have modified their opioid prescribing statutes over the past six years, allowing exceptions to the rules and extending the duration of prescriptions, but most have left their original prescribing restrictions intact. A recent lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union accuses the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services of launching previously unreported investigations into parents of transgender adolescents for possible child abuse under the direction of Gov. Greg Abbott who ordered the agency to handle certain medical treatments as possible crimes, reports the New York Times. Among the first to be investigated was an employee of the state protective services agency who has a 16-year-old transgender child and was placed on administrative leave last week and visited by an investigator from the agency, which is also seeking medical records related to her child.

According to the lawsuit, the state’s investigator told the parents that the only allegation against them was that their transgender daughter might have been provided with gender-affirming health care and was “currently transitioning from male to female.” The A.C.L.U. of Texas and Lambda Legal, a civil rights organization focusing on the L.G.B.T.Q. community, sought to block the request for medical records in the employee’s case and, more broadly, challenged the legitimacy of the investigation and the power of the governor to change the definition of child abuse and noting that other investigations have also begun. The groups argue in the suit that the directive by the governor was issued improperly under state law, ran afoul of the Texas Constitution and violated the constitutional rights of transgender youth, as well as of their parents. A bipartisan effort at the Georgia legislature is seeking to create a more uniform, consistent process to securing compensation for the state’s wrongfully convicted. One proposed measure, HB 1354, would set a ceiling and a floor for what those people can be paid and establish a panel of experts to vet their claims, reports the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Advocates say that the state’s current procedure for financial restitution is arduous and inconsistent, forcing exonerees through a frustratingly complex approval process that can take months if not years to complete, sometimes failing due to broader political dynamics, and ultimately pays greatly varying dollar amounts under equally inconsistent terms.

Proponents say the measure would make Georgia’s system fairer and bring the state in line with two-thirds of U.S. states and the federal government. The legislation would create a panel of political appointees — all subject matter experts in wrongful convictions or criminal justice — under the Claims Advisory Board to vet compensation claims. The panel would then recommend a dollar figure to the chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, who would include that in his budget request to lawmakers. The measure would also set clear criteria for who can and can’t qualify for compensation — exonerees would have to prove their innocence to be eligible — and establishes a range of $50,000 to $100,000 for how much each person should expect to receive based on each year they spent wrongfully imprisoned. |

HISTORY

April 2024

Categories |

© Walk 4 Change. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed